Short-term fasting-mimicking diets rapidly shift human metabolism. A single five-day fasting-mimicking cycle reduced body weight by ~1.7 kg, lowered fasting glucose by ~13–14 mg/dL, decreased insulin levels, and improved insulin sensitivity, while increasing ketone production—hallmarks of a fasting-like metabolic state.

Metabolic improvements were consistent across formulations. Both the standard ProLon and modified FMD2 diets produced similar improvements in glucose regulation, insulin resistance, and ketosis compared to a normal diet, indicating that brief caloric restriction alone is sufficient to drive these changes.

Autophagy engagement was formulation-dependent. Only the standard ProLon diet produced a detectable increase in autophagic flux, reflected by reduced LC3B accumulation and faster autophagosome degradation—suggesting that macronutrient composition, not just calorie reduction, influences cellular recycling.

Autophagic flux reflects process, not protein abundance. The study found no increase in autophagosome accumulation, but rather an acceleration of autophagic turnover—highlighting the importance of measuring autophagy dynamically rather than relying on static markers.

Cellular effects persisted beyond the fasting window. In the ProLon group, elevated autophagic flux remained detectable even after two days of normal eating, suggesting that short dietary stress may recalibrate cellular maintenance pathways beyond the intervention itself.

This is among the first human trials to measure autophagic flux directly. By assessing LC3B dynamics in immune cells across multiple timepoints, the study provides rare human evidence linking fasting-mimicking diets to a core hallmark of aging biology.

Findings are promising, but preliminary. The study was small and short-term, and it cannot determine whether repeated fasting-mimicking cycles produce lasting health benefits or disease risk reduction. Larger, longer trials will be needed to test durability, dose-response effects, and clinical relevance.

A Central Question in Fasting Biology

For decades, calorie restriction has stood out as one of the most consistent interventions shown to improve metabolic health and extend lifespan across species. In humans, reducing caloric intake can lower cardiometabolic risk factors and improve markers linked to aging-related disease. But there is a practical problem: maintaining a substantially calorie-restricted diet over months or years is difficult, and in some cases, may carry health risks. These challenges have prompted scientists to ask a different question, not whether eating less works, but whether the body’s beneficial response to fasting can be triggered in safer, more sustainable ways.

One such approach is the fasting-mimicking diet (FMD), a structured, short-term dietary intervention designed to reproduce the metabolic and hormonal effects of complete fasting, without requiring total food deprivation. Rather than eliminating calories altogether, FMD provides a carefully formulated, plant-based diet that is low in calories, protein, and sugars, but relatively high in unsaturated fats. This dietary phase lasts five days and is followed by a return to normal eating. The goal is not long-term restriction, but a periodic metabolic “reset” that nudges the body into a fasting-like physiological state.

Over the past decade, a growing body of randomized clinical trials has begun to show that intermittent cycles of a fasting-mimicking diet can produce measurable improvements in human health. In healthy adults, these dietary cycles have been associated with reductions in body fat, improvements in blood pressure, and favorable shifts in biomarkers linked to diabetes and cardiovascular disease. More intriguingly, some of these changes overlap with markers used to estimate biological aging and immune system function, suggesting that the effects of FMD may extend beyond conventional metabolic outcomes.

Researchers have also begun testing FMD in populations already burdened by chronic disease. Early studies in conditions such as multiple sclerosis, diabetes, Parkinson’s disease, inflammatory bowel disease, breast cancer, and Alzheimer’s disease hint that the same metabolic stress–recovery cycles may engage protective mechanisms relevant to disease progression. While these findings remain preliminary, they raise an important possibility: that short, periodic dietary interventions could influence biological processes shared across many seemingly unrelated diseases.

That unifying mechanism is increasingly thought to be autophagy—the cell’s internal recycling and repair system. Autophagy allows cells to identify, dismantle, and reuse damaged proteins, dysfunctional mitochondria, and other worn-out components. In youth, this process runs efficiently, helping maintain cellular integrity across tissues. With aging, however, autophagic activity declines. The result is a gradual accumulation of cellular debris that interferes with metabolism, promotes inflammation, and contributes to functional decline across organs ranging from brain and muscle to liver and immune cells.

This age-related erosion of cellular cleanup has emerged as a common thread linking many chronic diseases. Impaired autophagy has been implicated in neurodegeneration, metabolic dysfunction, immune dysregulation, and cancer—making it a central target in the emerging field of geroscience, which seeks to intervene in the biological processes that drive aging itself. Importantly, autophagy is not continuously “on.” Instead, it is activated by intermittent stress signals—periods when nutrients are scarce, energy demand is high, or cellular damage must be addressed. Fasting, exercise, and certain pharmacologic agents all appear to tap into this ancient survival pathway.

From this perspective, fasting-mimicking diets are not simply tools for weight loss or glucose control. They are hypothesized to function as autophagy-engaging interventions, delivering a temporary metabolic signal that shifts cells from growth and storage toward maintenance and repair. Similar logic underlies the study of compounds such as rapamycin, spermidine, and quercetin, which modulate nutrient-sensing pathways like AMPK and mTOR to intermittently activate autophagy without inducing chronic deprivation. In each case, the goal is not sustained stress, but a carefully timed trigger that prompts the cells cleanup machinery to recycle cellular waste for energy.

Yet despite the growing interest in FMD as a geroscience-based strategy, direct evidence linking these dietary cycles to changes in autophagy in humans has remained limited. Most clinical studies have focused on outward metabolic outcomes, leaving unresolved whether fasting-mimicking diets meaningfully engage the cellular recycling pathways thought to underlie their longer-term benefits.

To address this gap, we examine a randomized controlled trial published in the Journal of Geroscience titled “Effect of Fasting-Mimicking Diet on Markers of Autophagy and Metabolic Health in Human Subjects.” In this article, we analyze how the investigators designed the study, what they observed in terms of metabolic health, and—most importantly—whether the data support the hypothesis that fasting-mimicking diets activate measurable markers of autophagy in humans. In doing so, we aim to clarify what this research reveals about the biological reach of fasting-mimicking diets—and what questions remain open as autophagy moves from mechanistic insight to practical longevity strategy.

Study Design and Participants

To examine how fasting-mimicking diets influence human metabolism and cellular cleanup processes, the investigators conducted a small, tightly controlled clinical trial in healthy adults. Thirty participants were enrolled and randomly assigned to one of three dietary groups: a standard fasting-mimicking diet formulation known as ProLon, a modified version called FMD2, or a control group that continued eating normally. The study was open-label—meaning participants knew which diet they were assigned—but randomization was used to ensure that baseline differences between groups were minimized.

Rather than extending over weeks or months, the trial was designed to capture the physiological and molecular effects of a single fasting-mimicking cycle. Participants were followed for eight days, during which they completed four in-person visits: before the intervention began, during the fasting-mimicking phase, shortly after refeeding began, and at the study’s conclusion. At each visit, researchers collected vital signs, body measurements, and blood samples, allowing them to track changes as the metabolic stress of fasting unfolded and then resolved.

Blood samples were used to assess both safety and biological response. Standard clinical labs ensured participants remained healthy throughout the trial, while targeted measurements focused on metabolic markers such as glucose, insulin, insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), and ketones—molecules that reflect shifts in energy metabolism during fasting. Insulin sensitivity was estimated using a widely accepted calculation that integrates fasting glucose and insulin levels. Lipid profiles were measured at the beginning and end of the study to capture broader metabolic changes.

Crucially, the researchers also collected blood cells to examine molecular signals related to autophagy. These analyses were performed on peripheral blood mononuclear cells, a population of immune cells that can serve as a window into systemic cellular processes.

Dietary Interventions

Participants assigned to either fasting-mimicking group received prepackaged, five-day meal kits designed to induce a fasting-like metabolic state while still providing essential nutrients. The ProLon formulation has been used in previous clinical studies, while the FMD2 version was specifically engineered to reduce starch content and blunt post-meal glucose spikes—an adjustment intended to improve metabolic control. Both diets followed the same general structure: modest calorie intake on the first day, followed by more substantial calorie restriction over the remaining four days.

Those assigned to the control group continued their usual eating patterns, providing a reference point for interpreting changes seen in the fasting-mimicking groups. All meals for the FMD arms were standardized and provided by the same manufacturer, reducing variability in nutrient composition and calorie intake.

Measuring Autophagic Activity

To assess whether fasting-mimicking diets engaged autophagy in humans, the researchers employed a laboratory technique that estimates autophagic flux—a dynamic measure of how actively cells are breaking down and recycling internal components. Rather than simply measuring static levels of autophagy-related proteins, this approach compares cells treated with a compound that temporarily blocks autophagy to untreated cells. The difference between the two reflects how rapidly the process is occurring.

Blood samples for this analysis were collected under carefully controlled conditions, including standardized timing and overnight fasting, to minimize biological noise. Immune cells were isolated, processed, and stored using established protocols before being analyzed for changes in key autophagy-related proteins.

By combining short-term dietary intervention with repeated metabolic and molecular measurements, the study was designed not only to observe whether fasting-mimicking diets alter physiology, but to probe whether those changes extend to the cellular recycling systems long hypothesized to play a role in aging and disease resistance.

Metabolic Shifts During the Fasting-Mimicking Cycle

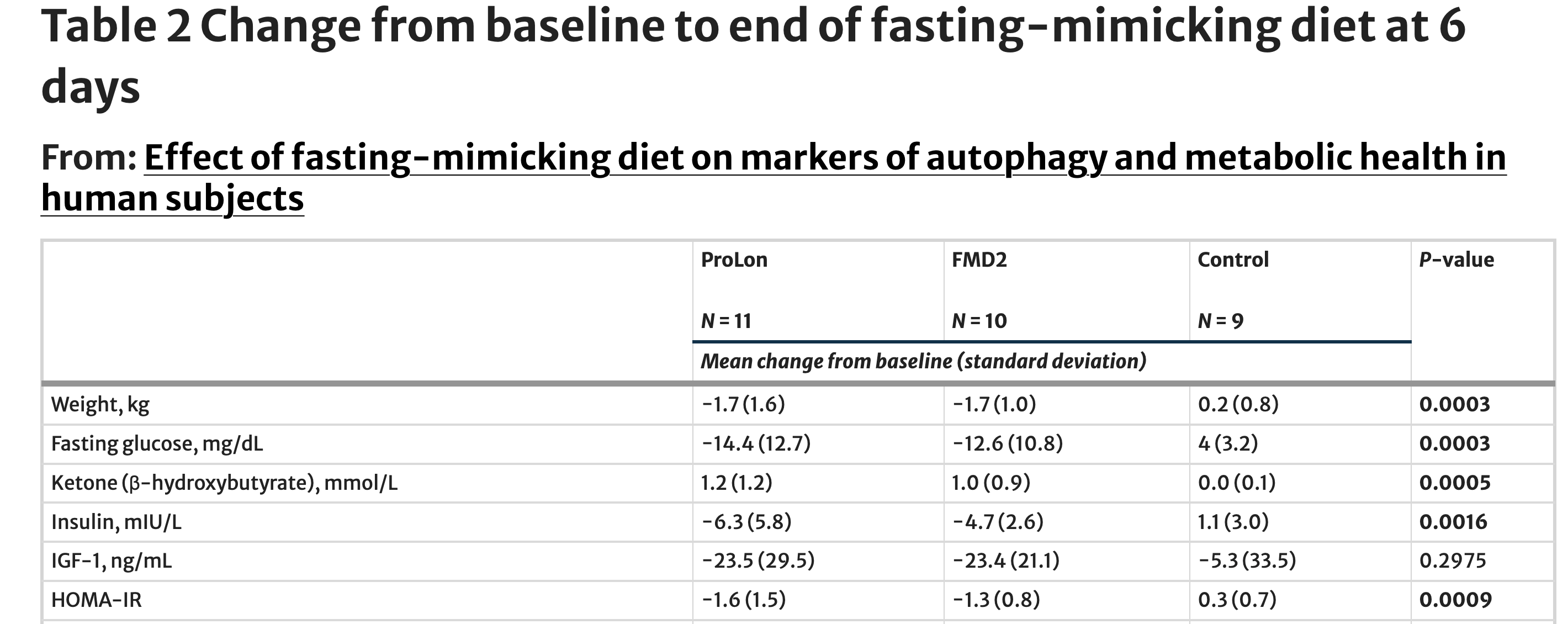

As participants progressed through the fasting-mimicking phase, the metabolic consequences of short-term dietary restriction became both measurable and internally consistent. By day six—near the end of the five-day intervention—participants in both fasting-mimicking diet groups showed coordinated changes across multiple markers that together signal a shift toward a fasting-like metabolic state.

Body weight declined by an average of 1.7 kilograms in both fasting-mimicking groups over just six days, while participants in the control group experienced a slight increase of 0.2 kilograms. This weight change was accompanied by a marked reduction in fasting glucose. Participants following the standard fasting-mimicking diet saw glucose levels fall by approximately 14 mg/dL, with a similar 13 mg/dL reduction observed in the modified FMD2 group. In contrast, glucose levels in the control group rose modestly during the same period.

The metabolic shift was further reflected in circulating ketone levels. β-hydroxybutyrate increased by roughly 1.0–1.2 mmol/L in the fasting-mimicking groups, a hallmark of reduced carbohydrate availability and increased reliance on fat-derived energy. Ketone levels remained essentially unchanged in the control group, reinforcing that these changes were driven by the dietary intervention rather than time or study participation alone.

Insulin dynamics moved in parallel. Fasting insulin concentrations declined by 6.3 mIU/L in the ProLon group and 4.7 mIU/L in the FMD2 group, while the control group showed a slight increase. When glucose and insulin were combined into an estimate of insulin resistance, both fasting-mimicking diets produced meaningful improvements: HOMA-IR decreased by 1.6 units in the ProLon group and 1.3 units in the FMD2 group. Over the same period, insulin resistance worsened slightly in the control group.

Not all metabolic markers shifted uniformly. Levels of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), a hormone often linked to growth and aging pathways, declined in both fasting-mimicking groups by more than 20 ng/mL, but variability across participants meant this change did not reach statistical significance when compared with the control group. This heterogeneity underscores an important feature of short-term human intervention studies: while metabolic responses to fasting are rapid and robust, hormonal adaptations may unfold on different timescales or require repeated dietary cycles.

Taken together, these data indicate that even a single cycle of a fasting-mimicking diet can rapidly alter core features of human metabolism—lowering glucose and insulin levels, improving insulin sensitivity, and inducing nutritional ketosis. These physiological shifts establish the metabolic conditions under which cellular maintenance pathways, including autophagy, are hypothesized to become activated.

How Did the Fasting-Mimicking Diets Affect Autophagy?

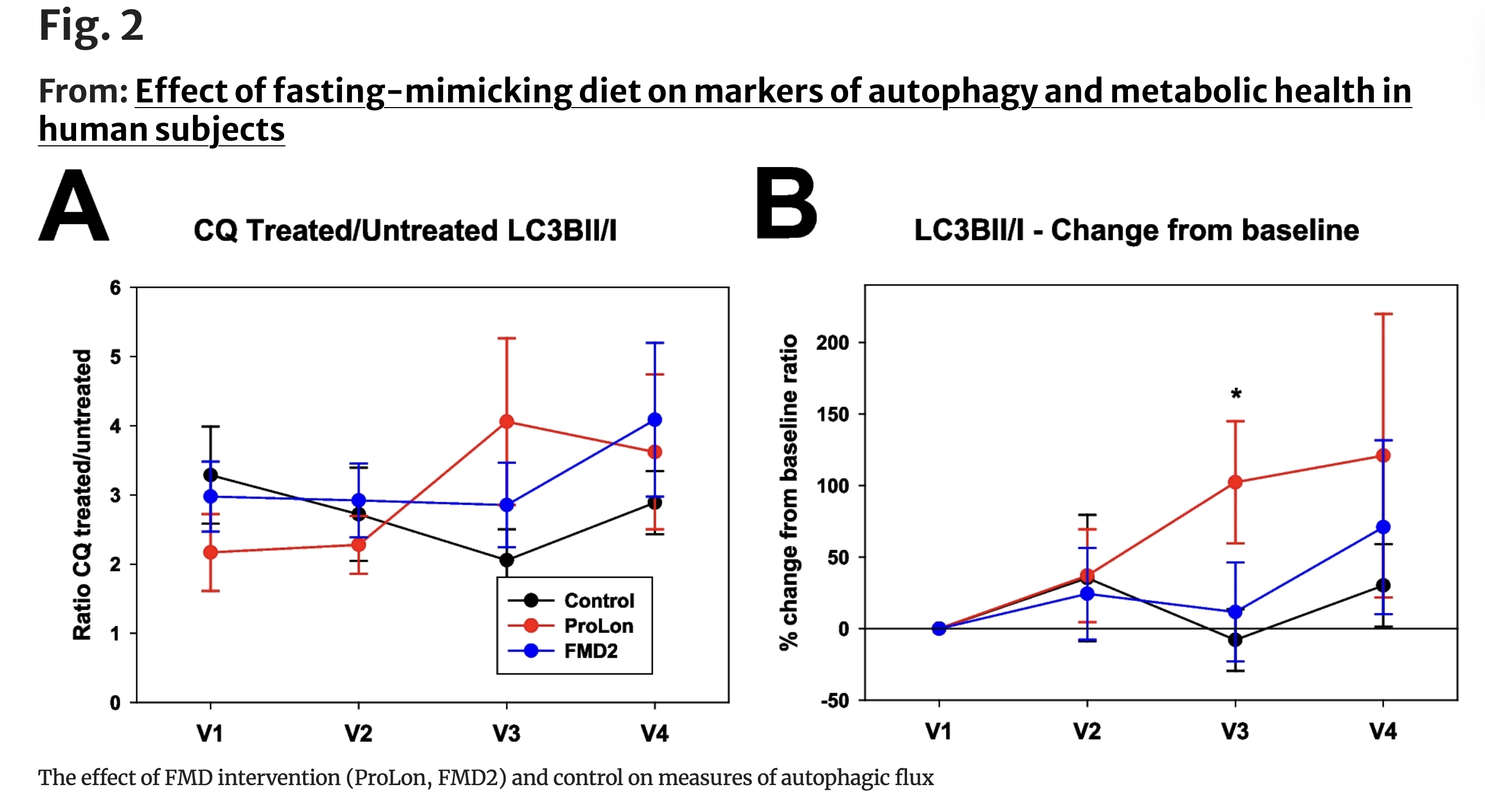

To determine whether fasting-mimicking diets engage cellular repair processes in humans, the investigators examined autophagic flux in circulating immune cells. Autophagy is a multi-step process, and flux refers not simply to whether it begins, but whether it runs to completion—from the formation of recycling vesicles to the final breakdown and reuse of cellular material.

At the center of this process is the autophagosome, a transient, double-membrane structure that forms around damaged proteins, dysfunctional mitochondria, and other cellular debris. Once assembled, the autophagosome fuses with a lysosome, whose enzymes dismantle its contents into reusable building blocks. If this final degradative step is impaired or slowed, autophagosomes accumulate—even if autophagy was initially activated. For this reason, counting autophagosomes alone can be misleading: accumulation may reflect either increased initiation or incomplete clearance.

To distinguish between these possibilities, the researchers measured levels of LC3B, a protein that becomes incorporated into the autophagosome membrane as it forms and is degraded once the autophagosome is cleared. The ratio of two LC3B forms therefore serves as a proxy for whether autophagosomes are being efficiently processed or are lingering unresolved within the cell.

When autophagosome accumulation was assessed directly—using untreated samples that reflect steady-state LC3B levels—no meaningful differences were observed among the three groups for most of the study. By day six, however, a divergence emerged. Participants in the control group showed a higher LC3B-II/LC3B-I ratio (1.3 ± 0.7) compared with both fasting-mimicking groups, which exhibited lower ratios (0.7 ± 0.4 in both ProLon and FMD2). This pattern persisted through day eight, approaching statistical significance.

Crucially, lower LC3B accumulation in this context does not indicate reduced autophagy. Instead, it is consistent with faster autophagosome turnover—meaning that damaged cellular components are being packaged, delivered, and degraded more efficiently. In other words, the recycling process appears to be moving through its final steps more rapidly.

That interpretation is reinforced by what happened when lysosomal degradation was temporarily blocked. Under these conditions, LC3B levels rose to a similar extent across all groups, indicating that fasting-mimicking diets did not increase the number of autophagosomes being formed. Rather, the distinguishing feature lay downstream—after autophagosomes formed—at the level of degradation and clearance.

When the researchers calculated autophagic flux by comparing LC3B levels in blocked versus unblocked samples, the dynamic effects of fasting became clearer. By day six, participants in the standard fasting-mimicking diet group showed a distinct upward trend in autophagic flux, reflecting faster autophagosomal turnover. Notably, this elevated flux persisted even after two days of normal eating, remaining higher on day eight than at baseline. In contrast, the modified FMD2 group exhibited a similar increase during the intervention, but the effect was transient—detectable on day six but no longer evident after refeeding.

Together, these quantitative shifts suggest that fasting-mimicking diets do not merely increase autophagy-related protein levels. Instead, they accelerate the cell’s recycling machinery, enhancing the rate at which intracellular material is processed and cleared. The persistence of this effect—particularly in the standard formulation—points to a lasting cellular response that extends beyond the fasting window itself.

...fasting-mimicking diets do not merely increase autophagy-related protein levels. Instead, they accelerate the cell’s recycling machinery, enhancing the rate at which intracellular material is processed and cleared.

What the Findings Suggest—and What They Don’t

Taken together, the results of this trial suggest that fasting-mimicking diets can rapidly reshape human metabolism—and, under certain conditions, may also engage the cellular recycling machinery thought to play a role in aging and disease resistance. Across both fasting-mimicking formulations, participants experienced improvements in metabolic health markers, including reductions in glucose, insulin resistance, and increased ketone production. These changes are consistent with prior clinical studies showing that even short periods of structured dietary restriction can induce a fasting-like metabolic state in humans.

What distinguishes this study, however, is its attempt to look beneath these outward metabolic shifts and examine whether they are accompanied by changes in autophagic flux—a dynamic marker of cellular maintenance rather than a static snapshot of autophagy-related proteins. Here, the findings are more nuanced. While both fasting-mimicking diets improved metabolic markers, only the standard ProLon formulation produced a detectable increase in autophagic flux, and this effect persisted briefly after normal eating resumed. The modified FMD2 diet showed a similar trend during the fasting period, but the signal faded after refeeding.

This divergence highlights an important and often underappreciated feature of dietary interventions: nutrient composition matters, not just calorie reduction. Although both diets imposed comparable caloric restriction, differences in macronutrient balance—particularly starch and protein content—may influence how deeply fasting signals propagate into cellular repair pathways. Emerging evidence from other trials supports this idea, suggesting that variations in protein content can differentially affect fat distribution, cardiovascular markers, gut microbiome composition, and autophagy-related gene expression.

From a broader perspective, the study reinforces a long-standing hypothesis in aging biology: that the benefits of calorie restriction may stem, at least in part, from its ability to modulate conserved nutrient-sensing pathways. Reduced nutrient availability dampens mTOR signaling and activates AMPK, shifting cells from growth-oriented programs toward maintenance and recycling. Autophagy sits at the center of this transition, helping clear damaged proteins and organelles, reduce inflammatory signaling, and maintain mitochondrial function—processes that decline with age and are disrupted in neurodegenerative, metabolic, and inflammatory diseases.

Yet the authors are careful not to overstate the implications. This was a small pilot study, involving a single cycle of dietary intervention and a limited number of participants. While the metabolic effects were robust, the autophagy signal—though intriguing—was modest and formulation-dependent. The study was not designed to assess long-term outcomes, repeated fasting cycles, or clinical endpoints related to disease risk or lifespan. Nor could it fully account for baseline differences in body weight between groups, a variable that may influence responses to dietary restriction, particularly in metabolic tissues.

Importantly, the absence of a strong association between baseline body weight and autophagic flux in this study does not rule out such effects in larger or more targeted populations. Preclinical research suggests that adiposity can shape how organisms respond to dietary stress, and future trials will need to explore whether fasting-mimicking diets produce different cellular responses in lean versus metabolically impaired individuals.

Why This Matters for Aging Research

Despite these limitations, the study occupies a meaningful place in the evolving landscape of geroscience. It is the first clinical trial to examine autophagic flux directly in humans during and after a fasting-mimicking intervention, rather than inferring autophagy from gene expression or animal models. That distinction matters: autophagy is a process, not a static state, and measuring its dynamics is essential for understanding whether interventions truly enhance cellular maintenance.

The findings suggest that short, periodic dietary interventions may be capable of nudging human cells toward a more resilient, self-renewing mode—at least transiently. Whether repeated cycles can produce cumulative or lasting effects remains an open question, as does the possibility of tailoring fasting-mimicking diets to specific metabolic or disease contexts.

In sum, this study does not claim that fasting-mimicking diets slow aging or prevent disease. What it offers instead is something more modest—and arguably more important: direct evidence that a brief, structured dietary intervention can influence not only metabolism, but also the cellular recycling machinery long implicated in aging biology. As larger and longer trials begin to explore these mechanisms in greater depth, fasting-mimicking diets may emerge as a practical tool for probing—and potentially modulating—the biology of human aging.

- Espinoza, S.E., Park, S., Connolly, G. et al. Effect of fasting-mimicking diet on markers of autophagy and metabolic health in human subjects. GeroScience (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-025-02035-4

Related studies