Animal vs. Plant Protein: Implications for Muscle and Healthspan

Protein needs for optimal healthspan are higher than the old RDA. Modern evidence supports daily intakes closer to 1.2–1.6 g/kg, especially for older adults and those who exercise regularly

Muscle Is a Longevity Organ. Skeletal muscle regulates glucose disposal, metabolic flexibility, and resilience to stress. Because aging muscle develops anabolic resistance, older adults require higher protein intakes (1.0–1.5 g/kg/day per PROT-AGE and ESPEN) to maintain lean mass and functional independence.

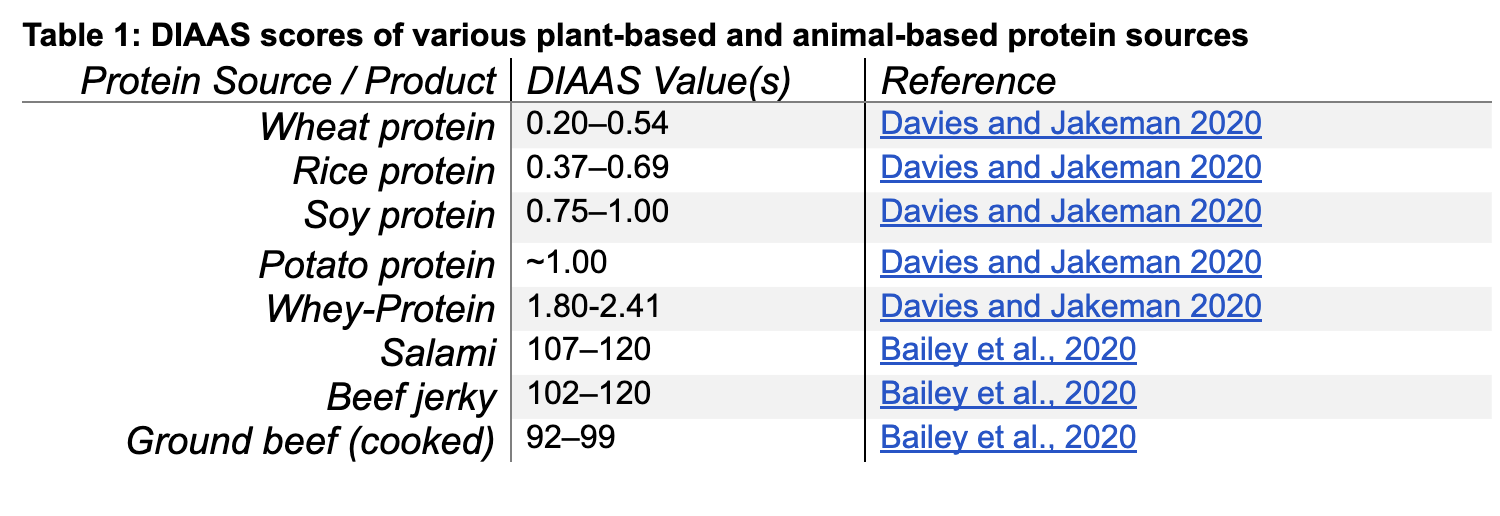

Protein quality matters as much as total intake. Not all whole food proteins deliver essential amino acids equally. The Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS) highlights meaningful differences in amino acid completeness and digestibility.

DIAAS Is the Gold Standard for Protein Quality. The Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS) evaluates essential amino acid content and true ileal digestibility. ≥100 = excellent; 75–99 = good; <75 = lower quality. Whey protein often scores ~180 or higher, reflecting exceptionally high essential amino acid density and digestibility.

Animal-based proteins consistently score highest for quality. Whey, casein, egg, and most meat sources reliably achieve “excellent” DIAAS scores, making protein adequacy straightforward when these sources are included.

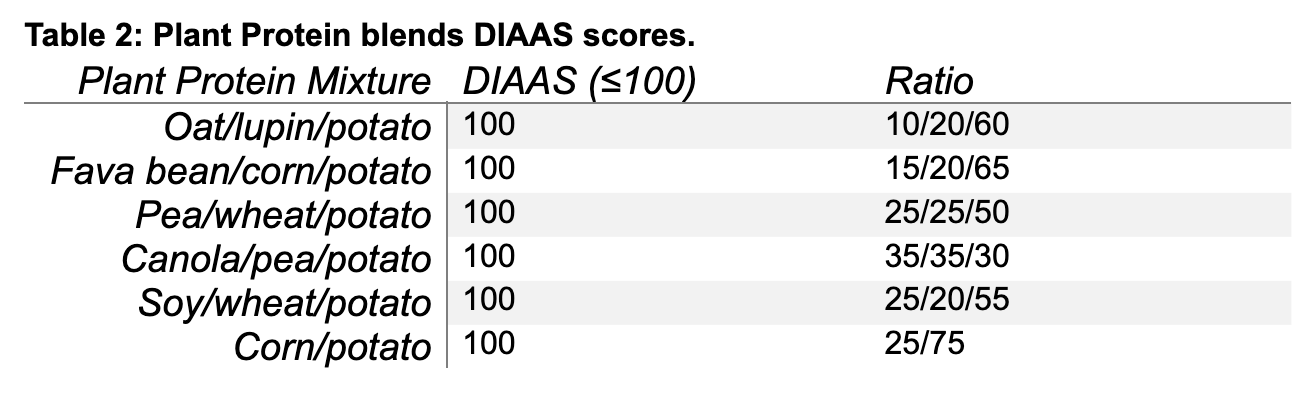

Plant-based proteins can be fully adequate but require a strategy. Most single-source plant proteins are lower in quality, yet carefully formulated blends (e.g., pea + wheat + potato or soy-based blends) can achieve excellent amino acid profiles.

Supplements are important tools. High-quality protein powders can help close intake gaps, particularly when aiming for 1.2–1.6 g/kg, but whole foods should remain the foundation of a longevity-focused diet.

Commercially available plant-protein blend supplements may not have the correct protein sources in the correct ratios, which means individuals may have to blend single-source protein supplements manually themselves.

Distribution Across Meals Enhances Anabolic Response. Evenly distributing ~30–40 g of protein per meal, particularly with adequate leucine content, improves muscle protein synthesis compared to skewed intake patterns.

Introduction: Protein Quality in the Age of Healthspan

Protein is often discussed as a simple macronutrient, one of three primary energy-containing raw materials that are found in foods or beverages alongside carbohydrates and fats. But from a healthspan perspective, protein is something far more consequential. It is the raw material of muscle, enzymes, hormones, immune signaling molecules, structural tissues, and mitochondrial machinery. Without adequate and appropriately structured protein intake, the body cannot repair, rebuild, or rejuvenate itself effectively over time.

Protein importance rises with advancing age. Beginning in young adulthood and throughout midlife, skeletal muscle mass and strength decline progressively, in a process known as muscle atrophy, or sarcopenia. This loss is not cosmetic. It predicts frailty, metabolic dysfunction, insulin resistance, falls, loss of independence, and mortality. Preserving muscle is increasingly recognized as one of the most powerful strategies for extending healthspan. Yet the ability to stimulate muscle protein synthesis becomes less efficient with age, a phenomenon termed anabolic resistance. In other words, older adults often require more protein, and higher-quality protein, to achieve the same biological effect that younger individuals achieve with less.

Protein itself is built from 20 amino acids, nine of which are essential and must be obtained through diet [1–3]. These essential amino acids, particularly leucine, act not only as building blocks but as signaling molecules that activate muscle protein synthesis through pathways such as mTOR. The pattern and bioavailability of these amino acids determine whether a protein source merely meets minimal requirements or truly supports anabolic resilience.

This distinction becomes especially important as more individuals adopt plant-forward or fully plant-based diets for ethical, environmental, or metabolic reasons. While plant proteins can certainly contribute meaningfully to total intake, they vary widely in amino acid composition and digestibility compared to many animal-derived proteins [4]. Public dietary guidelines have largely focused on preventing deficiency. They have not been designed to optimize muscle retention, metabolic flexibility, or longevity.

This creates an increasingly relevant question for healthspan-focused individuals: Are all proteins functionally equivalent when the goal is not survival, but long-term functional capacity?

In this review, we examine current scientific evidence on optimal protein intake for health and performance, explore differences between animal- and plant-based protein sources, and provide practical guidance for individuals seeking to optimize protein intake, particularly those relying on plant-based diets or supplements.

The Consequences of Insufficient Protein Intake

Protein inadequacy is not only a dietary shortfall, it is a physiological stressor. When protein intake fails to meet the body’s needs, the consequences ripple across multiple systems, particularly those most critical for long-term resilience.

One of the earliest and most visible effects is the loss of skeletal muscle mass and function. With aging, muscle protein breakdown gradually exceeds synthesis, contributing to sarcopenia, the progressive loss of strength and mobility that underlies frailty, falls, and loss of independence [5]. Insufficient dietary protein accelerates this trajectory. Over time, what begins as subtle weakness can compound into reduced metabolic health, impaired glucose regulation, and diminished capacity to recover from illness or injury.

Protein deficiency also compromises immune function and wound healing. Amino acids serve as building blocks not only for muscle tissue, but for antibodies, enzymes, and structural proteins required to repair damaged tissue. Inadequate intake may manifest as slower healing, greater susceptibility to infection, hair thinning, skin fragility, and reduced libido, all signals of impaired protein-dependent physiology [5].

From a performance and adaptation standpoint, protein plays an even more dynamic role. Exercise adaptation, the process through which the body becomes stronger or more aerobically efficient, depends fundamentally on the synthesis of new proteins within muscle tissue [6].

Strength training increases contractile proteins such as actin and myosin. Endurance training enhances mitochondrial proteins that improve metabolic efficiency. In both cases, dietary protein provides the amino acid substrate required to build these structural and enzymatic components.

Without adequate protein, recovery from individual training sessions is blunted [7], and long-term improvements in strength, power, and endurance are compromised [8,9]. The body cannot construct what it does not have the materials to build.

For individuals focused on healthspan, this distinction becomes critical. Muscle is not merely aesthetic tissue, it is a metabolic organ, a glucose sink, and a determinant of longevity [6]. Preserving muscle mass and function reduces risk of metabolic disease, supports insulin sensitivity, and protects against frailty. Adequate protein intake is therefore not simply about meeting minimum dietary recommendations; it is about preserving structural resilience across decades.

How Much Protein Is Required Each Day?

For decades, the official recommended dietary allowance (RDA) for protein in adults has been set at approximately 0.8 g/kg of body mass per day [10]. Based on current average body weights in the United States (~90 kg for men and ~78 kg for women), this equates to roughly 72 grams per day for men and 62 grams per day for women [11].

Importantly, the 0.8 g/kg value was originally designed to prevent overt deficiency in otherwise healthy, sedentary individuals not to optimize muscle mass, metabolic function, or long-term resilience. In recent years, this distinction has become increasingly clear. Emerging evidence from aging, metabolic, and exercise science has prompted a meaningful shift in protein recommendations. Updated guidelines now align more closely with research data that suggest that most adults, particularly those focused on preserving muscle and metabolic health, may benefit from daily protein intakes closer to 1.2–1.6 g/kg, with even higher targets in some populations [12-14].

Muscle mass is one of the strongest predictors of healthy aging, physical independence, and metabolic stability. Because skeletal muscle becomes progressively resistant to anabolic stimulation with age, a phenomenon often referred to as “anabolic resistance” higher protein intakes are required to achieve the same muscle-preserving effect seen in younger individuals.

For older adults (>65 years), prominent expert groups including the PROT-AGE Study Group [13] and the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) [14] recommend intakes of 1.0–1.5 g/kg per day to attenuate age-related muscle loss and support functional independence. For individuals engaging in regular resistance or endurance training, the International Society of Sports Nutrition recommends 1.4–2.0 g/kg per day [16], with intakes above 2.0 g/kg sometimes used in strength athletes or during periods of caloric restriction.

Although the previous 0.8 g/kg target may be sufficient to avoid deficiency, for those pursuing healthspan optimization, preserving lean mass, enhancing recovery, and maintaining insulin sensitivity, daily intake closer to ~1.6 g/kg appears more consistent with the evidence.

Practical Implications: How to Reach the Updated Targets

Shifting from 0.8 g/kg to 1.6 g/kg effectively doubles daily protein intake. For a 90 kg male, that means increasing from ~72 grams to ~144 grams per day. For a 78 kg female, from ~62 grams to ~125 grams per day.

Achieving this consistently requires intentional dietary planning. Several practical strategies can help:

- Distribute protein evenly across meals (e.g., ~30–40 g per meal rather than skewing intake toward dinner)

- Prioritize high-leucine protein sources that stimulate muscle protein synthesis effectively

- Use supplemental protein strategically, particularly post-exercise or when whole-food intake is insufficient

- Combine complementary plant proteins when following plant-based patterns

- Anchor each meal around a protein source, rather than treating protein as a side component

For individuals consuming predominantly plant-based diets, achieving 1.2–1.6 g/kg may require greater volume, strategic food combinations, or supplementation due to lower protein density and variability in amino acid composition. The evolving science of protein intake makes one point clear: preventing deficiency is not the same as optimizing physiology.

The Case for Protein Supplements: Strategy, Not Shortcut

As protein recommendations shift upward, particularly toward the 1.2–1.6 g/kg range, a practical challenge emerges: consistently hitting those targets through whole foods alone is not always simple or achievable.

For many individuals, consuming 100–150 grams of protein per day requires deliberate meal planning, repeated preparation, and careful food selection. High-protein whole foods such as lean meats, dairy, legumes, eggs, and fish are nutrient-dense, but they are also calorically dense and often time-intensive to prepare. When appetite is low, schedules are compressed, or total caloric intake is being moderated for body composition goals, meeting elevated protein needs becomes logistically difficult.

This is where protein supplementation moves from optional convenience to strategic longevity tool. Protein powders, ready-to-drink beverages, and fortified foods offer a concentrated source of amino acids with minimal preparation time and relatively low additional carbohydrate or fat load. When integrated alongside whole foods, not in place of them, supplements can help bridge the gap between theoretical protein recommendations and real-world adherence. For individuals seeking to optimize muscle preservation, recovery, metabolic resilience, or longevity, this flexibility can meaningfully improve consistency.

The global supplement market reflects this demand. Animal-derived protein powders, particularly whey, remain dominant, accounting for more than half of global protein supplement sales [17]. Their popularity is driven by convenience, digestibility, and strong evidence supporting their anabolic potential.

At the same time, consumer interest is diversifying. Ethical preferences, environmental considerations, lactose intolerance, and plant-based dietary patterns have accelerated growth in plant-based protein supplements [18,19]. Industry projections suggest plant-based products may approach ~14% of global market share by 2032 [17], signaling a substantial shift in dietary trends.

But increased availability raises a more nuanced question and one central to healthspan optimization: Are all protein supplements created equal?

Meeting a numerical protein target is only part of the equation. Protein quality, amino acid composition, digestibility, and anabolic signaling capacity determine whether a protein supplement meaningfully supports muscle protein synthesis and long-term metabolic health.

Protein Quality Determines Biological Outcomes

Meeting daily protein targets is only part of the equation. Two individuals can consume the same number of grams of protein per day, yet experience different physiological outcomes depending on the quality of the protein they consume.

This distinction becomes especially important when relying heavily on supplemental protein and even more so when those supplements are plant-based.

At its core, protein quality depends on two fundamental variables:

- Amino acid profile: Does the protein contain sufficient amounts of all nine essential amino acids?

- Digestibility and bioavailability: how much of those amino acids are actually absorbed and available for use in muscle, immune tissue, enzymes, and structural repair?

If a protein source is deficient in even one essential amino acid or if that amino acid is poorly digested, the body’s ability to build or repair tissue becomes constrained. In practical terms, this means that someone could consume “adequate” total protein by weight yet still fail to optimize muscle protein synthesis or recovery if the protein source is low quality.

For individuals focused on healthspan, preserving muscle mass, metabolic resilience, immune robustness, and recovery capacity, this distinction matters.

Measuring Protein Quality: The Role of DIAAS

Several methods have historically been used to evaluate protein quality. However, the current gold standard is the Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS), developed by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations [20].

Unlike older scoring systems, DIAAS evaluates protein quality based on:

• The amount of each essential amino acid per gram of protein

• The true ileal digestibility of each amino acid

True ileal digestibility refers to how much of a given amino acid is absorbed by the end of the small intestine, the point at which nutrient absorption is largely complete [21].

To calculate DIAAS:

- The milligrams of each essential amino acid per gram of protein are measured.

- Each is multiplied by its true ileal digestibility.

- That value is divided by an age-specific reference requirement.

- The lowest-scoring essential amino acid becomes the DIAAS score for that protein source.

This “limiting amino acid” concept reflects biological reality: if one essential amino acid is insufficient, it limits the body’s ability to use the others effectively.

A DIAAS score:

- ≥100 is considered excellent

- 75–99 is considered good

- <75 indicates lower quality

Why Whey Protein Scores So Highly - DIAAS Score Example

To understand protein quality in practical terms, consider whey protein.

The Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS) is calculated as:

DIAAS (%) = (Digestible indispensable amino acid (mg per g protein)) / (Reference amino acid requirement (mg per g protein)) × 100

In whey protein concentrate, lysine is typically the lowest-scoring indispensable amino acid (i.e., the “limiting” amino acid).

- Whey lysine content: ~81 mg per gram of protein

- Adult reference requirement: 45 mg per gram of protein

DIAAS (%) = (81 mg per g protein / 45 mg per g protein) x 100

DIAAS (%) = 1.8 x 100

DIAAS (%) = 180

This yields a DIAAS score of approximately 180, far exceeding the ≥100 threshold considered “excellent” [18,23].

Importantly, the “limiting amino acid” defines the overall score. Even if all other essential amino acids exceed requirements, the lowest one determines the final DIAAS value. In whey’s case, even the lowest essential amino acid dramatically surpasses the human reference requirement.

In practical terms, whey protein does not simply meet essential amino acid needs it substantially exceeds them. This high DIAAS score helps explain why whey protein reliably stimulates muscle protein synthesis, supports recovery, and is often considered the benchmark supplemental protein source.

Why This Matters for Plant-Based Proteins

Not all protein sources score equally on measures of amino acid completeness and digestibility. Many plant proteins are relatively lower in one or more essential amino acids most commonly lysine, methionine, or leucine and may demonstrate modestly reduced digestibility due to fiber content, antinutrients, or structural characteristics of the plant protein matrix.

However, this distinction must be interpreted in context.

Recent evidence suggests that when total daily protein intake is sufficiently high particularly at or above approximately 1.6 g/kg/day differences in protein quality between plant- and animal-derived sources become substantially less impactful on outcomes such as muscle protein synthesis and lean mass retention [26]. At this intake level, the total supply of essential amino acids appears adequate to overcome modest limitations in digestibility or single limiting amino acids.

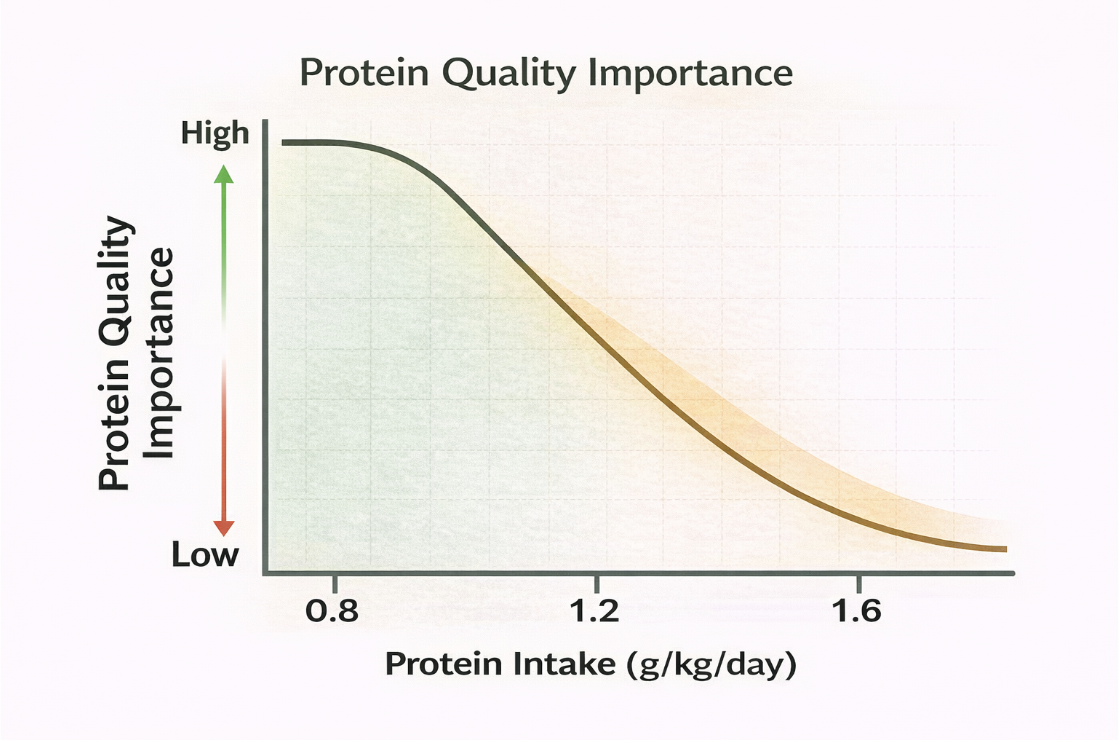

In practical terms, this means that for individuals consistently consuming ≥1.6 g/kg/day of protein, the source of protein becomes less critical than total intake (Figure 2). This intake level also aligns closely with contemporary recommendations emerging from longevity and exercise research, as well as updated guidance supporting higher protein targets for active and aging adults.

Figure 2. Protein Quality Importance vs Total Protein Intake. Adapted from Understanding Dietary Protein Quality: Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Scores and Beyond. By Matthews, J. J., et al., 2025, The Journal of nutrition, 155(10), 3152–3167.

That said, when protein intake is closer to minimum thresholds (e.g., near 0.8–1.0 g/kg/day), protein quality becomes more consequential. At lower intakes, amino acid limitations and digestibility differences can meaningfully affect anabolic signaling and tissue remodeling.

For those following plant-based diets, several strategies help ensure adequacy:

- Consuming total protein intakes in the range of ≥1.2–1.6 g/kg/day

- Strategically blending complementary protein sources

- Paying attention to leucine density per serving

- Selecting higher-DIAAS plant proteins (e.g., soy or potato-based products)

Thus, the discussion is not one of superiority, but of strategy. At lower protein intakes, quality differences matter more. At higher intakes, particularly around 1.6 g/kg/day, the body’s essential amino acid requirements are generally met regardless of source, provided intake is distributed appropriately across meals.

This threshold concept reframes the plant-versus-animal debate: achieving sufficient total protein may be the more decisive factor for healthspan than the origin of the protein itself.

The next section examines how animal- and plant-based protein supplements compare within this framework of amino acid density, digestibility, and practical application.

Comparing the Quality of Plant-Based and Animal-Based Protein Sources

When evaluating protein sources, it is helpful to separate total protein intake from protein quality. Both matter but they are not identical. Many animal-derived protein sources consistently achieve excellent DIAAS scores (≥100), meaning they provide all essential amino acids in sufficient amounts and with high digestibility. Examples include eggs, dairy proteins such as whey and casein, pork, beef, and poultry [5,23]. Even certain processed animal proteins (e.g., cured meats) demonstrate high digestibility and complete amino acid profiles [23].

For individuals consuming mixed diets that meet total protein requirements and include a meaningful proportion of animal-derived protein, meeting essential amino acid needs is generally straightforward. In these cases, food selection can often prioritize personal preference, sustainability, or culinary diversity without significant concern about amino acid adequacy.

Plant-based protein sources, including cereals, legumes, nuts, seeds, vegetables, and starchy roots also contribute meaningfully to total protein intake [18]. Common examples include wheat, rice, beans, lentils, potatoes, and maize [4,18]. However, as standalone sources, plant proteins tend to show greater variability in DIAAS scores. Most do not individually reach the ≥100 “excellent” threshold, with notable exceptions such as soy and potato protein, which perform comparatively well [4,18].

Importantly, this variability does not mean plant-based diets are inadequate or inferior. Rather, it reflects differences in amino acid distribution and digestibility. Many plant proteins are relatively lower in one or more essential amino acids; for example, cereals are typically lower in lysine, while legumes may be lower in methionine. When consumed in isolation and in insufficient total amounts, these limitations can constrain the body’s ability to fully utilize dietary protein.

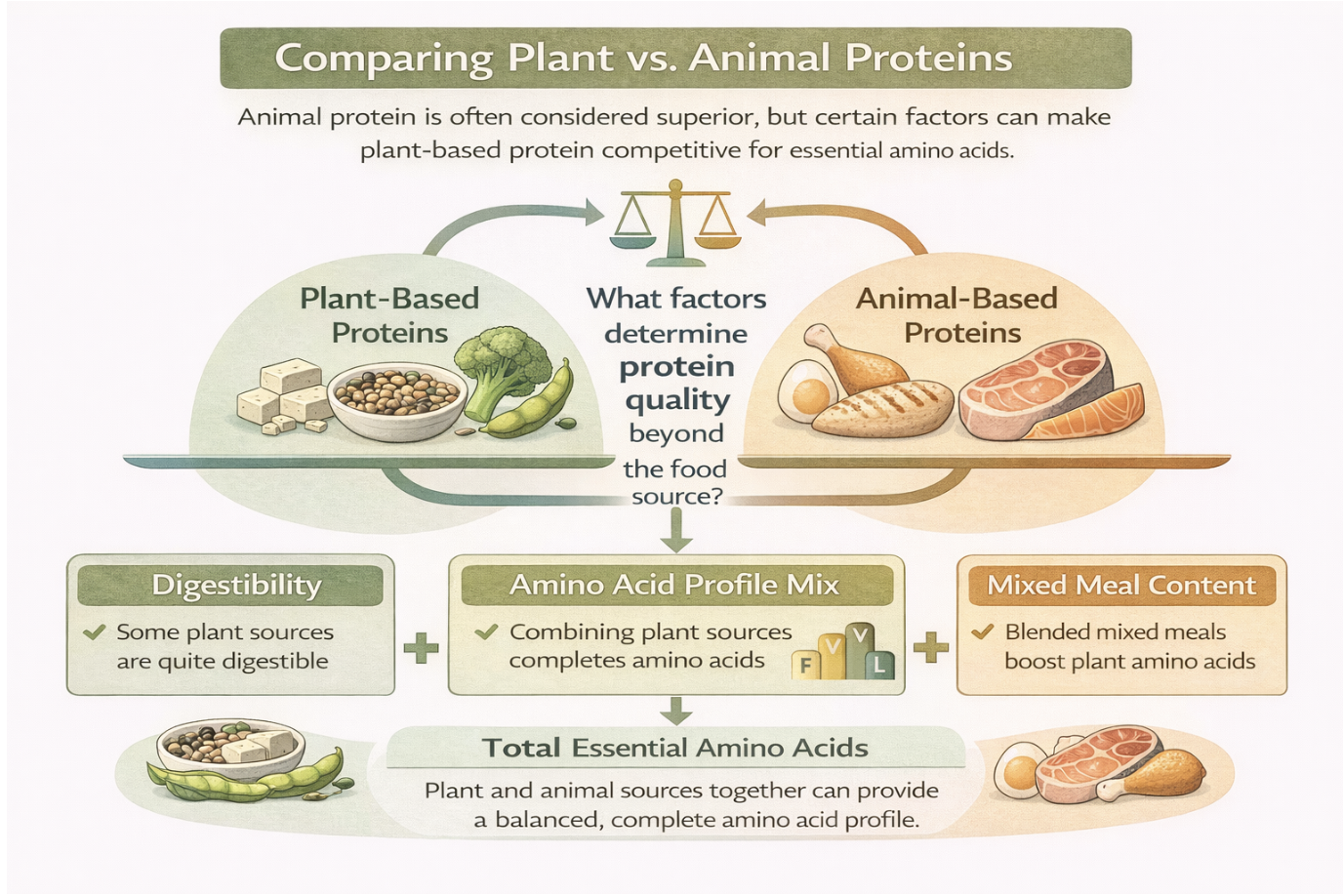

However, dietary context matters. When plant proteins are strategically combined (e.g., legumes with grains), their amino acid profiles complement one another, improving overall adequacy. Additionally, consuming slightly higher total protein intake can compensate for modest reductions in digestibility (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Comparison of Plant and Animal Protein Quality

From a healthspan perspective, the key consideration is not whether a diet is plant-based or animal-based, but whether it reliably delivers:

- Adequate total daily protein

- Sufficient essential amino acids

- High enough digestibility to support muscle maintenance and repair

For individuals relying primarily on plant-based protein, particularly older adults or those engaging in regular resistance training, greater intentionality around protein quantity, diversity, and quality becomes especially important.

This distinction becomes even more relevant when we turn to protein supplements, where the form of protein chosen can meaningfully influence anabolic response, recovery, and long-term muscle preservation.

Plant-Based vs. Animal-Based Protein Supplements

Processing, Quality, and Practical Equivalence

When protein is concentrated into supplement form, the differences between whole foods narrow but they do not disappear entirely. Animal-derived protein supplements such as whey and casein are produced from high-quality whole-food sources that already possess excellent amino acid profiles. As a result, their Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Scores (DIAAS) are typically very high, often well above 100 and in many cases exceeding 150 [18]. This means they provide all essential amino acids in amounts that comfortably exceed adult reference requirements, with excellent digestibility. For this reason, whey protein in particular is often considered a “reference standard” for protein quality in supplementation research.

Plant-based protein supplements, by contrast, originate from a much wider range of raw materials, including peas, soy, rice, hemp, seeds, corn, and other legumes and starches [24]. This diversity creates variability. Many of the underlying whole-food sources of plant proteins have lower DIAAS values (<0.90 or <100 on the percentage scale), often due to one limiting amino acid (for example, lysine in cereals or methionine in legumes) [18,24].

The Role of Processing

Importantly, the act of isolating and concentrating protein can improve quality relative to the original whole food. Removing fiber and other non-protein components improves digestibility. For example, whey protein concentrate has a higher DIAAS score than whole milk powder from which it is derived [18].

The same principle applies to plant proteins. Modern processing techniques can increase digestibility and concentrate essential amino acids beyond what is present in the intact plant food [4,24]. Therefore, plant-based protein supplements are generally higher quality than their whole-food equivalents.

However, even after processing, single-source plant protein isolates typically remain somewhat lower in DIAAS compared with leading animal-based proteins such as whey [22]. The difference is not usually dramatic but it can be biologically relevant in contexts where maximal muscle protein synthesis or protein efficiency is the goal.

Protein Blending: A Practical Solution

Where plant-based supplementation becomes particularly compelling is in strategic blending.

Protein blending combines complementary plant sources to offset each other’s limiting amino acids. Legumes tend to be lower in methionine but richer in lysine; grains tend to be lower in lysine but adequate in sulfur amino acids. When combined appropriately, these deficits can be “covered,” resulting in a complete and well-balanced amino acid profile.

Published examples of plant protein blends achieving DIAAS scores ≥100 include combinations such as:

These blends demonstrate that plant-based supplements can achieve technically “excellent” protein quality when formulated intentionally.

It is worth noting that in nearly all high-scoring blends, at least one component is a relatively high-quality plant protein (most commonly potato or soy). This has practical implications:

- A blended plant protein supplement is generally superior to a single low-quality isolate.

- If selecting a single-source plant protein, soy or potato are typically the strongest standalone options.

The Real-World Perspective

For most healthspan-focused individuals consuming adequate total protein 1.2 g/kg/day to 1.6 g/kg/day, small differences in protein quality may not meaningfully affect outcomes, particularly if intake is distributed across meals and overall energy intake is sufficient.

However, when protein intake is borderline, low, calorie intake is restricted, or optimizing muscle protein synthesis is a priority (e.g., aging adults, strength athletes, individuals in energy deficit), protein quality becomes more relevant.

In short:

- Animal-based protein supplements tend to provide reliably high amino acid density and digestibility.

- Plant-based supplements can achieve comparable adequacy when carefully selected or blended.

- Single-source, lower-quality plant isolates may require either larger doses or strategic combination with other proteins to match the anabolic potential of gold standard proteins.

Framed this way, the question is not whether plant proteins are “good” or “bad,” but whether they are formulated and dosed appropriately for the individual goal at hand.

Choosing Between Plant-Based and Animal-Based Protein Supplements

The evidence reviewed throughout this article consistently shows that animal-based protein sources and supplements, particularly dairy-derived proteins such as whey and casein, demonstrate higher protein quality scores compared to most single-source plant proteins. For individuals who prioritize simplicity, affordability, and maximal protein quality with minimal decision burden, whey or casein protein remains a highly efficient option. These products are widely available, cost-effective, palatable, and consistently exceed the threshold for excellent protein quality.

Within whey specifically, certain protein fractions offer additional functional advantages beyond amino acid density alone. Alpha-lactalbumin, a naturally occurring, tryptophan-rich whey fraction, maintains the exceptional digestibility and anabolic properties of whey while also increasing tryptophan availability. Because tryptophan is a precursor to serotonin and melatonin, higher-tryptophan whey preparations may support sleep quality, metabolic regulation, and cognitive resilience alongside muscle protein synthesis. For individuals interested in this more targeted application, we explore the science behind alpha-lactalbumin in greater detail in a dedicated research review.

Beef protein powders represent another viable animal-derived option. While published DIAAS data on beef protein powders specifically are limited, whole beef demonstrates excellent protein quality [25]. Provided a product is marketed as a complete protein rather than collagen or isolated peptides, beef-based supplements are likely sufficient for individuals who prefer to avoid dairy.

For individuals who choose plant-based supplementation for ethical, environmental, or digestive reasons, high-quality options are absolutely achievable. Although many single-source plant proteins demonstrate lower DIAAS scores, thoughtfully formulated blends can reach scores of 100, meeting the threshold for excellent protein quality [4]. Importantly, once a protein achieves a DIAAS score of 100, additional increases do not confer additional biological benefit. In other words, a properly designed plant blend can be functionally equivalent to whey in its ability to deliver essential amino acids.

The key caveat is formulation and sourcing. Achieving excellent protein quality with plant proteins often requires specific source combinations, such as the inclusion of soy or potato protein in appropriate proportions, and commercial products vary widely in composition. In addition, recent independent testing has highlighted variability in heavy metal content, including lead, in certain plant-based protein powders [27]. The Clean Label Project is an initiative aimed at evaluating and improving the transparency and safety of supplements [27]. Nonetheless, because protein supplements are often consumed daily, selecting products that undergo rigorous third-party purity testing is prudent.

When thoughtfully selected and manufactured with attention to both amino acid composition and contaminant screening, both animal-based and plant-based protein supplements can effectively support health, performance, and longevity goals.

Conclusion

Protein adequacy is not simply about hitting a daily gram target; it is about ensuring that sufficient essential amino acids are delivered in a form the body can effectively use. Animal-derived protein supplements such as whey and casein consistently demonstrate excellent protein quality and offer a convenient, reliable means of meeting elevated protein needs. For individuals who prioritize simplicity and maximal certainty in amino acid delivery, these options remain highly effective.

That said, plant-based protein supplementation can also support protein adequacy when approached thoughtfully. While many single-source plant proteins demonstrate lower and more variable quality, carefully formulated blends, particularly those incorporating higher-quality sources such as soy or potato, can achieve DIAAS scores consistent with excellent protein status. Ultimately, supplementation should complement, not replace, a foundation of whole-food nutrition. Whether derived from plant or animal sources, the optimal protein strategy is one that reliably supports muscle preservation, metabolic resilience, and long-term healthspan while aligning with individual preferences and values.

- Lopez, M.J., Mohiuddin, S.S., 2025. Biochemistry, Essential Amino Acids, in: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557845/

- Wu, G., 2009. Amino acids: metabolism, functions, and nutrition. Amino Acids 37, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00726-009-0269-0

- Phillips, S.M., Fulgoni, V.L., Heaney, R.P., Nicklas, T.A., Slavin, J.L., Weaver, C.M., 2015. Commonly consumed protein foods contribute to nutrient intake, diet quality, and nutrient adequacy. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 101, 1346S-1352S. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.114.084079

- Herreman, L., Nommensen, P., Pennings, B., Laus, M.C., 2020. Comprehensive overview of the quality of plant- And animal-sourced proteins based on the digestible indispensable amino acid score. Food Science & Nutrition 8, 5379–5391. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.1809

- Wu, G., 2016. Dietary protein intake and human health. Food Funct. 7, 1251–1265. https://doi.org/10.1039/C5FO01530H

- Egan, B., Sharples, A.P., 2023. Molecular responses to acute exercise and their relevance for adaptations in skeletal muscle to exercise training. Physiological Reviews 103, 2057–2170. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00054.2021

- Naderi, A., Rothschild, J.A., Santos, H.O., Hamidvand, A., Koozehchian, M.S., Ghazzagh, A., Berjisian, E., Podlogar, T., 2025. Nutritional Strategies to Improve Post-exercise Recovery and Subsequent Exercise Performance: A Narrative Review. Sports Med 55, 1559–1577. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-025-02213-6

- Tagawa, R., Watanabe, D., Ito, K., Otsuyama, T., Nakayama, K., Sanbongi, C., Miyachi, M., 2022. Synergistic Effect of Increased Total Protein Intake and Strength Training on Muscle Strength: A Dose-Response Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Sports Med - Open 8, 110. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-022-00508-w

- Witard, O.C., Hearris, M., Morgan, P.T., 2025. Protein Nutrition for Endurance Athletes: A Metabolic Focus on Promoting Recovery and Training Adaptation. Sports Med 55, 1361–1376. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-025-02203-8

- Institute of Medicine, 2005. Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids. National Academies Press, Washington, D.C. https://doi.org/10.17226/10490

- Fryar, C., Gu, Q., Afful, J., Carroll, M., Ogden, C., 2025. Anthropometric Reference Data for Children and Adults: United States, August 2021–August 2023. National Center for Health Statistics (U.S.). https://doi.org/10.15620/cdc/174595

- Trombetti, A., Reid, K.F., Hars, M., Herrmann, F.R., Pasha, E., Phillips, E.M., Fielding, R.A., 2016. Age-associated declines in muscle mass, strength, power, and physical performance: impact on fear of falling and quality of life. Osteoporos Int 27, 463–471. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-015-3236-5

- Bauer, J., Biolo, G., Cederholm, T., Cesari, M., Cruz-Jentoft, A.J., Morley, J.E., Phillips, S., Sieber, C., Stehle, P., Teta, D., Visvanathan, R., Volpi, E., Boirie, Y., 2013. Evidence-Based Recommendations for Optimal Dietary Protein Intake in Older People: A Position Paper From the PROT-AGE Study Group. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 14, 542–559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2013.05.021

- Deutz, N.E.P., Bauer, J.M., Barazzoni, R., Biolo, G., Boirie, Y., Bosy-Westphal, A., Cederholm, T., Cruz-Jentoft, A., Krznariç, Z., Nair, K.S., Singer, P., Teta, D., Tipton, K., Calder, P.C., 2014. Protein intake and exercise for optimal muscle function with aging: Recommendations from the ESPEN Expert Group. Clinical Nutrition 33, 929–936. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2014.04.007

- Tipton, K.D., 2008. Protein for adaptations to exercise training. European Journal of Sport Science 8, 107–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461390801919102

- Jäger, R., Kerksick, C.M., Campbell, B.I., Cribb, P.J., Wells, S.D., Skwiat, T.M., Purpura, M., Ziegenfuss, T.N., Ferrando, A.A., Arent, S.M., Smith-Ryan, A.E., Stout, J.R., Arciero, P.J., Ormsbee, M.J., Taylor, L.W., Wilborn, C.D., Kalman, D.S., Kreider, R.B., Willoughby, D.S., Hoffman, J.R., Krzykowski, J.L., Antonio, J., 2017. International Society of Sports Nutrition Position Stand: protein and exercise. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition 14, 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12970-017-0177-8

- Grandview Research, 2023. Protein Supplements Market Size, Share Industry Report, 2033 [WWW Document]. URL https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/protein-supplements-market (accessed 12.2.25).

- Davies, R.W., Jakeman, P.M., 2020. Separating the Wheat from the Chaff: Nutritional Value of Plant Proteins and Their Potential Contribution to Human Health. Nutrients 12, 2410. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082410

- de Boer, J., Aiking, H., 2021. Favoring plant instead of animal protein sources: Legitimation by authority, morality, rationality and story logic. Food Quality and Preference 88, 104098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2020.104098

- Moughan, P.J., Lim, W.X.J., 2024. Digestible indispensable amino acid score (DIAAS): 10 years on. Front. Nutr. 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2024.1389719

- Stein, H.H., Fuller, M.F., Moughan, P.J., Sève, B., Mosenthin, R., Jansman, A.J.M., Fernández, J.A., de Lange, C.F.M., 2007. Definition of apparent, true, and standardized ileal digestibility of amino acids in pigs. Livestock Science, 10th International Symposium on Digestive Physiology in Pigs, Denmark 2006, Part 2 109, 282–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.livsci.2007.01.019

- Adhikari, S., Schop, M., de Boer, I.J.M., Huppertz, T., 2022. Protein Quality in Perspective: A Review of Protein Quality Metrics and Their Applications. Nutrients 14, 947. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14050947

- FAO, 2013. Dietary protein quality evaluation in human nutrition: report of an FAO Expert Consultation [on Protein Quality Evaluation in Human Nutrition], 31 March - 2 April, 2011, Auckland, New Zealand, FAO food and nutrition paper. Presented at the Expert Consultation on Protein Quality Evaluation in Human Nutrition, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome. https://www.fao.org/ag/humannutrition/35978-02317b979a686a57aa4593304ffc17f06.pdf

- Sharma, K., Zhang, W., Rawdkuen, S., 2025. Dietary Plant-Based Protein Supplements: Sources, Processing, Nutritional Value, and Health Benefits. Foods 14, 3259. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14183259

- Bailey, H.M., Mathai, J.K., Berg, E.P., Stein, H.H., 2020. Most meat products have digestible indispensable amino acid scores that are greater than 100, but processing may increase or reduce protein quality. Br J Nutr 124, 14–22. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114520000641

- Matthews, J. J., Arentson-Lantz, E. J., Moughan, P. J., Wolfe, R. R., Ferrando, A. A., & Church, D. D. (2025). Understanding Dietary Protein Quality: Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Scores and Beyond. The Journal of nutrition, 155(10), 3152–3167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tjnut.2025.07.005

- Bandara, S. B., Towle, K. M., & Monnot, A. D. (2020). A human health risk assessment of heavy metal ingestion among consumers of protein powder supplements. Toxicology reports, 7, 1255–1262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxrep.2020.08.001

Related studies