A Novel Synergistic Strategy for Hair Loss Prevention and Reversal: Rapamycin, Finasteride, and Minoxidil

Prefer to listen? Hit play for a conversational, audio‑style summary of this article’s key points.

AGA reflects aging biology—not just hormones: Beyond DHT sensitivity, hair follicle decline arises from stem-cell dysfunction, mitochondrial slowdown, impaired autophagy, extracellular matrix remodeling, and accumulation of senescent cells—hallmarks of tissue aging that erode the follicle’s ability to re-enter anagen.

Autophagy is a central switch for follicle regeneration: Across mouse models, human organ cultures, and Hair Follicle Stem Cell (HFSC)-specific assays, autophagy activation consistently triggers the telogen-to-anagen transition, increases HFSC proliferation, extends anagen duration, and rejuvenates aging stem cells—positioning autophagy as a required driver of growth rather than a passive housekeeping process.

mTOR inhibition restores the follicle’s regenerative program: Rapamycin rebalances chronically elevated mTORC1 signaling—common in aging follicles—reactivating autophagy, clearing damaged mitochondria and proteins, reducing inflammatory SASP activity, and attenuating early fibrotic remodeling. The result is a microenvironment more responsive to pro-growth signals.

Traditional therapies target complementary pathways: Finasteride reduces androgenic stress by lowering DHT; minoxidil enhances vascular perfusion and nutrient delivery. Both help preserve follicle function but do not directly repair senescence, stem-cell exhaustion, or metabolic decline—key contributors to long-term dormancy.

Rapamycin “primes” follicles for better therapeutic response: By rejuvenating HFSCs and softening fibrotic tissue, rapamycin enhances the follicle’s ability to respond to minoxidil’s vascular effects and finasteride’s hormonal relief. This priming effect increases regenerative readiness and may overcome treatment plateaus seen with monotherapy.

Combination therapy offers multidimensional repair: Clinical and preclinical data suggest superior outcomes when rapamycin, finasteride, and minoxidil are used together. Each agent addresses a distinct axis of follicular decline—hormonal (finasteride), vascular/metabolic (minoxidil), and regenerative/cellular (rapamycin)—forming a biologically coherent, synergistic strategy.

Human organ culture data confirm translational relevance: Autophagy activation in human follicles mirrors findings in mice: HFSC proliferation increases, anagen lengthens, and stem-cell characteristics rejuvenate. These conserved responses strengthen the therapeutic rationale for autophagy-targeted interventions in people.

Lifestyle factors modulate the follicular microenvironment: Stress, sleep disruption, inflammatory burden, nutrient deficiencies, thyroid imbalance, and hormone ratios influence anagen maintenance and HFSC behavior. Optimizing these inputs strengthens the biological foundation on which pharmacologic therapies act.

Microneedling amplifies topical efficacy: Randomized trials show microneedling significantly enhances the response to minoxidil, likely through HFSC signaling, Wnt activation, improved absorption, and vascular stimulation. Weekly use before topical application provides the strongest evidence base.

A regenerative model of hair restoration is emerging: By integrating geroscience-based therapeutics like rapamycin with traditional agents, hair loss treatment is shifting from symptom management toward cellular rejuvenation. Targeting autophagy and HFSC biology may define the next evolution in AGA therapy.

Hair loss is a common concern affecting millions of men and women worldwide. Hair loss progression is influenced by genetic, biological, and lifestyle factors. Recent advances in fields of dermatological and longevity research have introduced innovative combinations that offer promise for more effective prevention and reversal of hair thinning and baldness. This review focuses on a cutting-edge strategy: the synergistic combination of topical rapamycin with established FDA-approved agents, finasteride and minoxidil. We will dive into the research and discuss the synergy between rapamycin, which primes hair follicles at the cellular level for enhanced efficacy of the proven topical treatments. This unique pairing blends three effective therapeutics to promote cell health and hair follicle growth, especially when paired with healthy habits.

Introduction

For decades, hair loss—particularly androgenetic alopecia (AGA)—has been viewed almost entirely through a hormonal lens. The prevailing explanation centered on dihydrotestosterone (DHT) and its outsized influence on genetically susceptible follicles. But emerging research now paints a far more nuanced picture: hair thinning is not merely a consequence of androgen signaling, but a reflection of aging biology unfolding within the follicle itself [1].

AGA, the most common form of hair loss, begins when certain follicles exhibit an inherited sensitivity to DHT, the potent androgen produced from testosterone by 5α-reductase [1]. Under sustained DHT exposure, the follicle’s growth program behaves as though its internal signaling has begun to dim. The cues that once generated robust, thick hair shafts weaken across successive cycles, yielding finer strands and shortening the duration of active growth. Over time, the follicle enters longer resting phases, becomes more difficult to reactivate, and gradually drifts toward dormancy.

Yet DHT alone cannot explain why follicles lose resilience with age, why miniaturization accelerates over time, or why some follicles respond to treatment while others remain unresponsive. Increasingly, scientists recognize that AGA is not simply a hormonal condition—it is a localized expression of tissue aging. The microenvironment surrounding the follicle undergoes its own decline: energy delivery slows, waste clearance falters, inflammatory signals accumulate, and stem cells become less responsive. In biological terms, this reflects a coordinated cascade involving stem-cell dysfunction, cellular senescence, metabolic slowdown, and reduced autophagy—all of which erode the follicle’s regenerative capacity.

Viewed through this broader lens, AGA becomes more than a cosmetic concern. It is a model for understanding how aging disrupts the function of regenerative tissues and why restoring that function requires more than manipulating hormones or blood flow. This perspective has catalyzed a new generation of therapeutic strategies informed by both endocrinology and geroscience—approaches that target not only DHT and vascular support but also the deeper cellular programs that allow follicles to regenerate in the first place.

To understand how these age-related shifts reshape follicle behavior—and why restoring regenerative capacity requires more than blocking hormones—it helps to zoom out and examine the architecture of the hair cycle itself. The follicle does not grow continuously; instead, it moves through a tightly regulated rhythm of growth, regression, rest, and renewal. This cycle is where the earliest signs of hormonal stress and cellular aging first appear, and where modern therapies exert their most measurable effects.

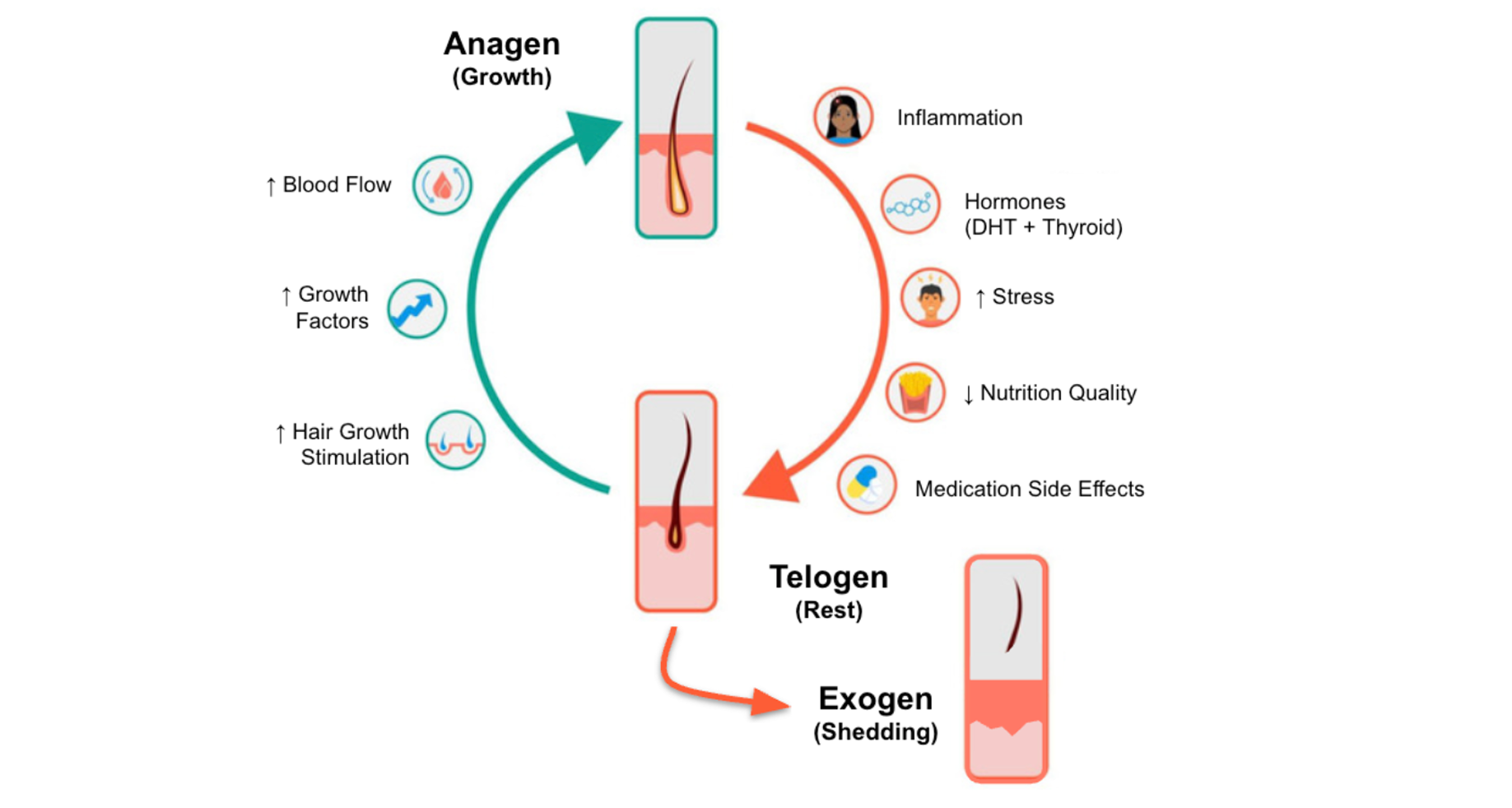

The Hair Growth Cycle

Each hair follicle operates within a recurring biological rhythm—a cycle of growth, regression, rest, and renewal that repeats dozens of times over a lifetime [5]. This cycle unfolds across four phases: anagen (active growth), catagen (a brief regression phase), telogen (rest), and exogen (shedding). In a healthy scalp, the vast majority of follicles—typically 85–90%—reside in anagen at any given moment, fueled by active stem-cell populations and robust signaling from the dermal papilla. The remaining follicles lie in telogen or briefly transition through catagen and exogen, a steady turnover that naturally replaces about 100–150 hairs each day [5].

Under normal conditions, the total number of follicles remains remarkably stable. What shifts with age, stress, hormonal changes, or disease is the balance between growing and resting hairs. In a healthy scalp, the anagen-to-telogen ratio averages around 12:1 to 14:1, reflecting a strong bias toward active growth [4]. In AGA, this ratio collapses to roughly 5:1 as follicles spend progressively less time in anagen and more time in telogen. Other conditions show different patterns: telogen effluvium narrows the ratio to around 8:1, while alopecia areata may approach parity—evidence of widespread follicular dormancy [4].

This balance is not accidental—it is governed by a network of genetic, hormonal, metabolic, and environmental inputs. A follicle’s ability to move fluidly from one phase to the next depends on intact stem-cell function, sufficient vascular supply, healthy mitochondrial activity, and an inflammatory environment kept in check. When those systems falter, the cycle loses its rhythm, and follicles become more susceptible to the cumulative effects of aging and androgenic stress.

As the following sections explore, therapies that restore this rhythm—whether by improving blood flow, reducing hormonal pressure, enhancing autophagy, or reactivating stem cells—represent the foundation of modern strategies to prevent or reverse hair thinning.

The Biology of Follicular Aging: Follicle Stem Cell & Dermal Papilla Communication

As follicles cycle through anagen, catagen, and telogen over many decades, their ability to regenerate does not remain constant. Aging introduces a series of subtle but cumulative impairments that gradually erode the follicle’s responsiveness to growth signals. Understanding these changes is essential for explaining why some follicles recover after stress while others slide into long-term dormancy—a state central to androgenetic alopecia.

One of the most important determinants of whether a follicle can re-enter anagen is the communication between hair follicle stem cells (HFSCs) and dermal papilla cells (DPCs). HFSCs provide the proliferative force that assembles each new hair shaft, while DPCs function as the follicle’s regulatory center, issuing the biochemical cues that initiate growth. You can think of DPCs as setting the tempo and HFSCs as carrying out the movement—an internal rhythm that keeps the follicle cycling smoothly.

In youth, this rhythm is tightly synchronized. With age, however, the tempo becomes irregular: DPCs lose transcriptional vigor and produce fewer pro-growth factors—such as Wnt/β-catenin, FGF7, VEGF, and IGF-1—while HFSCs become less responsive to these cues as mitochondrial efficiency declines, molecular damage accumulates, and inflammatory signals rise. Even when external hormonal or vascular conditions appear favorable, the follicle struggles to transition from telogen back into anagen. This breakdown in HFSC–DPC communication is increasingly recognized as a core driver of follicular dormancy and progressive thinning [36, 37].

Layered onto this disrupted signaling are additional hallmarks of aging biology:

- Cellular senescence, introducing a persistent inflammatory presence within the niche

- Metabolic slowdown, accompanied by impaired mitochondrial energetics

- Reduced autophagy, allowing damaged proteins and organelles to accumulate

- Extracellular matrix remodeling, altering the structural support HFSCs need for activation

Together, these factors reshape the follicular ecosystem, pushing it toward a state that is less regenerative and more resistant to reactivation.

Recent studies suggest that restoring this lost HFSC–DPC dialogue may be one of the most promising interventions for age-related hair loss. By re-establishing the biochemical “conversation” between these two cell populations, emerging therapies appear capable of reawakening dormant follicles and restoring a healthier, more reliable growth cycle [36, 37].

Before exploring these interventions in detail, we must first examine another major contributor to disrupted follicle function: cellular senescence.

Cellular Senescence in Hair Follicles

When faced with an injury or damage, every cell in the body eventually faces a biological crossroads: repair the damage, divide again, or stop. When the burden of stress or injury becomes too high, many cells choose a third option—cellular senescence. In this state, cells permanently exit the cell cycle but remain metabolically active. In small amounts, senescence is protective: it prevents damaged cells from dividing and becoming cancerous. But as we age, senescent cells accumulate and begin releasing a potent mix of inflammatory molecules, proteases, and growth factors known collectively as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). The accumulation of these senescent cells interferes with normal tissue function.

In the hair follicle, senescent cells appear most prominently within dermal papilla cells (DPCs) and hair follicle stem cells (HFSCs)—the two populations most essential for initiating anagen. SASP factors such as IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α trigger local inflammation, disrupt the Wnt/β-catenin and FGF signaling required to initiate anagen, and alter the extracellular matrix that HFSCs rely on for anchoring.

As this occurs, the follicle’s internal communication system begins to accumulate molecular “static.” Even when the follicle attempts to transition from telogen to anagen, the necessary cues can become distorted or weakened, making activation less reliable and growth phases shorter. Over time, this contributes to the hallmark features of follicular aging: delayed anagen entry, reduced hair shaft thickness, and gradual miniaturization.

Microscopic analyses of balding scalp samples reflect these changes. Compared with non-balding follicles, balding DPCs show elevated levels of p16^INK4a and p21, classical markers of senescence, as well as clear signs of oxidative DNA damage and mitochondrial dysfunction [40, 41, 42].

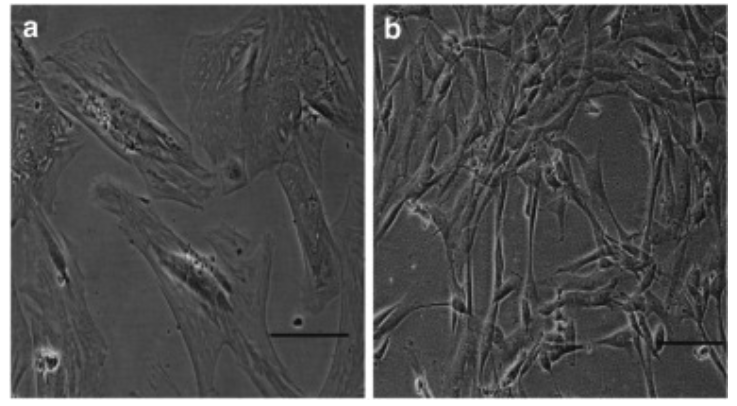

When DPCs from balding scalps are grown in the lab (a process known as in vitro culture), they show early signs of aging, a condition termed 'premature senescence'. This means that these cells appear to age faster than expected. They exhibit characteristics typical of old cells, such as changes in their appearance and function.

In a study that evaluated the role of senescence in AGA balding, nearly all the DPCs from the balding scalp had lost their proliferative capacity [42]. Moreover, these cells change their shape, transitioning from their typical elongated fibroblastic shape to a larger form with pronounced stress filaments—a hallmark of senescence in fibroblasts.

To establish further whether this loss of proliferative capacity was a consequence of premature senescence, the researchers used a marker of senescence, a marker called senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-Gal).

In the balding DPCs, the samples showed strong positive SA-β-Gal staining in the majority of cells, whereas the non-balding DPCs were all negative for SA-β-Gal, although occasional positive cells were observed. Through the increase of SA-β-Gal positive cells, it's clear that the balding DPCs had entered into a state of senescence [42].

Taken together, these findings suggest that follicular aging is not merely the loss of hair-producing cells, but the persistence of dysfunctional ones. Reversing or removing senescent cells may help restore the youthful, pro-growth signaling environment that allows follicles to re-enter the hair cycle. We will discuss some of the experiments used to test this hypothesis later in this review.

Autophagy as a Regenerative Switch in Hair Follicles

If cellular senescence represents a buildup of damage that interferes with regeneration, autophagy is the countervailing process that helps prevent this decline. Autophagy—literally “self-eating”—is the cell’s internal recycling system. It identifies damaged proteins, lipids, and organelles, breaks them down, and repurposes their components. In doing so, autophagy preserves energy balance, maintains mitochondrial health, and prevents the accumulation of cellular debris that can push cells toward senescence.

In the hair follicle, autophagy acts as a kind of regenerative switch. During the transition from telogen (rest) to anagen (growth), autophagy surges, clearing accumulated damage and restoring the metabolic conditions necessary for hair follicle stem cells (HFSCs) to activate. When this process is robust, HFSCs can reliably enter the growth program that generates new hair shafts. But when autophagy declines—whether due to age, chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, or nutrient excess—the follicle loses its ability to reset between cycles. Damaged mitochondria accumulate, stress signals rise, and HFSCs become slower to respond.

Recent studies highlight how closely autophagy is tied to follicular longevity. Impaired autophagy correlates with shortened anagen phases, reduced HFSC activity, and early hair thinning. Conversely, enhancing autophagy has been shown to reactivate dormant HFSCs, improve their metabolic readiness, and extend the functional lifespan of the follicle.

What the studies tell us about autophagy and hair growth

To move beyond theoretical models and test whether autophagy activation can directly accelerate hair regeneration, a research group at UCLA tested several autophagy-stimulating compounds, including α-ketoglutarate (α-KG), α-ketobutyrate (α-KB), rapamycin, and metformin—agents known to stimulate autophagy [13].

Empirical Assessment and Findings

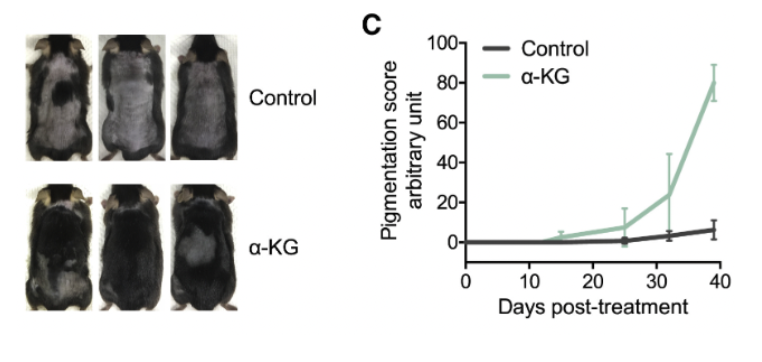

To establish a comparative framework, the study incorporated minoxidil, a widely recognized vasodilator used in the treatment of pattern hair loss, serving as a benchmark due to its common application as a positive control in hair growth research. In the experimental design, male mice at 6.5 weeks of age and in the telogen phase of the hair cycle were topically administered α-KG or the minoxidil control on an alternate-day basis. This methodological choice was motivated by the objective of identifying treatments that are readily adaptable for human application.

The results were striking. Mice treated with α-KG showed a rapid onset of skin pigmentation by day 12, a well-established indicator that follicles have begun transitioning into the anagen phase. Pigmentation reflects the activity of follicular melanocytes, which only engage when follicles re-enter growth. [13]

This finding sharply contrasted with the control group, where pigmentation was either negligible or entirely absent until day 39, the conclusion of the study period for histological and biochemical analyses. Notably, hair growth in the α-KG-treated mice initiated within 5–7 days post-treatment from the pigmented areas, culminating in extensive hair coverage by day 39. Conversely, the control group displayed minimal to no hair growth throughout the study duration. [13]

Taken together, these results demonstrate that activating autophagy with α-KG can dramatically accelerate the transition from telogen to anagen, outperforming even the minoxidil benchmark. The speed and magnitude of this effect suggest that autophagy functions as a key regulator—if not the central regulator—of early follicle activation.

Targeting mTOR to Re-Engage Autophagy in Aging Hair Follicles

Following the promising outcomes associated with metabolic activators of autophagy, the UCLA research team turned its attention to rapamycin, a compound known for its potent autophagy-enhancing properties, to evaluate its efficacy in hair regeneration.

Rapamycin exerts its effects through the inhibition of the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR), an enzyme pivotal to regulating cellular growth, protein synthesis, and metabolism. mTOR serves as a critical sensor and effector in cellular responses to nutrient availability, toggling between promoting cellular growth in nutrient-rich conditions and activating autophagy to recycle cellular components under nutrient scarcity.

With age, however, mTOR activity becomes chronically elevated—keeping cells in a perpetual growth state and suppressing autophagic clearance. This imbalance contributes to stem-cell dysfunction and diminished regenerative capacity in multiple tissues, including the hair follicle. By inhibiting mTOR, rapamycin restores the natural oscillation between growth and repair, enabling autophagy to re-engage. [13]

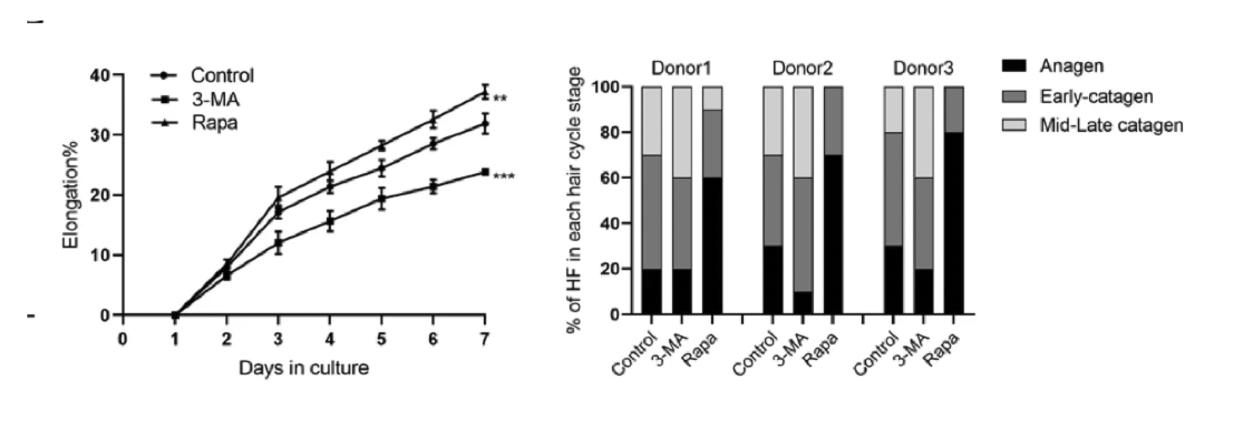

The study employed two pharmacological agents: rapamycin, known for its autophagy-activating properties, and 3-methyladenine (3-MA), an inhibitor of autophagy. This approach was designed to offer insights into how manipulating autophagy levels could impact HFSC behavior and the broader hair follicle cycle.

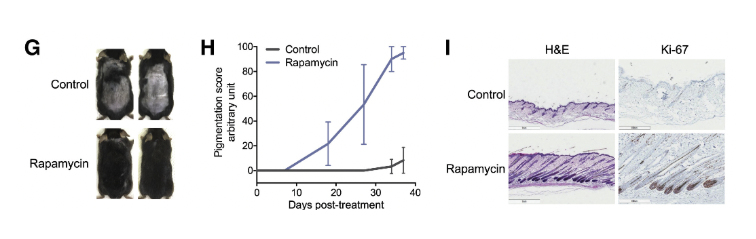

Evaluating Rapamycin's Efficacy in Hair Regeneration

In their investigation, the UCLA researchers applied rapamycin topically to the skin of mice during the telogen phase, the resting stage of the hair cycle, to ascertain its potential to expedite the transition to the anagen phase, characterized by active hair growth. The rapamycin treatment resulted in a noticeable acceleration of hair regeneration. The results were clear: rapamycin accelerated the transition into anagen, producing earlier and more uniform hair regrowth compared to controls.

Histological analysis confirmed what was visible on the surface—follicles in rapamycin-treated areas had already entered structural stages characteristic of anagen. [13]

Moreover, the analysis revealed a significant upsurge in autophagy markers in the skin tissue of mice treated with rapamycin, underscoring the enhanced autophagic activity induced by mTOR inhibition. These findings not only corroborate the critical role of autophagy in hair follicle health and regeneration but also highlight the therapeutic potential of rapamycin as an autophagy activator in promoting hair growth.

Verifying Autophagy-Induced Hair Regeneration

While rapamycin’s effects strongly suggested that autophagy drives early follicle activation, the UCLA team sought a more definitive test. Rapamycin inhibits mTOR, but mTOR controls many cellular processes; to isolate autophagy as the true driver, the researchers turned to SMER28, a molecule that activates autophagy through an mTOR-independent mechanism.

When SMER28 was applied topically to mouse skin, autophagy markers rose sharply—yet mTOR signaling remained unchanged. This clean separation confirmed that SMER28 was triggering autophagy directly, without influencing upstream nutrient-sensing pathways.

The biological response mirrored what was observed with rapamycin:

- Follicles entered anagen earlier,

- Hair regrowth accelerated, and

- Histological analyses confirmed a coordinated shift into the growth phase.

To test whether autophagy was truly necessary for this effect, the team introduced autophinib, a molecule that blocks autophagosome formation and effectively shuts down autophagy. When autophinib was paired with SMER28, the regenerative effects disappeared entirely—no early pigmentation, no accelerated anagen entry, no meaningful hair growth.

This two-part experiment delivered a clear conclusion: autophagy is not simply associated with follicle activation—it is required for it.

When autophagy is engaged, follicles transition into growth; when autophagy is blocked, regeneration stalls.

This two-part experiment delivered a clear conclusion: autophagy is not simply associated with follicle activation—it is required for it. When autophagy is engaged, follicles transition into growth; when autophagy is blocked, regeneration stalls.

Autophagy Within Stem Cells: The Crucial Link to Regeneration

These findings naturally raised the next question: How does autophagy influence the cells most responsible for regenerating hair—the hair follicle stem cells (HFSCs) themselves?

A follow-up study examined autophagy activity directly within HFSCs across the hair cycle. Using co-localization assays for autophagy markers and the HFSC marker K15, researchers mapped autophagic activity from early telogen through anagen entry. A consistent pattern emerged:

When researchers measured autophagy markers in HFSCs, a clear pattern emerged.

- During most of telogen, autophagy was low.

- As follicles approached the telogen-to-anagen transition, autophagy rose sharply, reflected in a marked increase in LC3-positive puncta—clear indicators that the autophagic machinery had switched on.

- p62 levels dropped, a key sign that the cell’s recycling system was actively clearing damaged proteins; p62 accumulates when autophagy is blocked and decreases when the process is functioning efficiently.

- Once anagen began, autophagy subsided, returning to baseline as the follicle transitioned fully into its growth program.

This timing is not incidental. HFSCs require a burst of metabolic readiness to exit quiescence and re-enter the growth program. Autophagy provides this reset by clearing damaged organelles and restoring energy balance. When autophagy rises, HFSCs can activate; when it falters, they remain dormant.

To test causality, researchers manipulated autophagy pharmacologically:

- 3-methyladenine (3-MA) was used to block autophagy

- Rapamycin was used to stimulate it

The results were unambiguous:

- Blocking autophagy delayed anagen entry and suppressed HFSC activation.

- Stimulating autophagy with rapamycin significantly enhanced HFSC activation and increased proliferation.

Hair follicles treated with rapamycin transitioned into anagen more readily and showed stronger early growth signals than controls.

When autophagy is strong, follicles recover their regenerative rhythm; when it weakens, the hair cycle becomes sluggish, irregular, and prone to thinning.

Human Data: Exploring Autophagy's Effects on Human HFSC Activation and Hair Follicle Cycle Through Organ Culture Models

To determine whether the autophagy-driven effects observed in mice extend to humans, researchers turned to a human hair follicle organ culture model—a powerful in vitro system that preserves the follicle’s architecture and microenvironment. This model allowed the team to study human HFSC behavior under controlled conditions while maintaining the complex signaling networks that guide real-world follicle cycling.

The results closely mirrored those seen in mice. When autophagy was stimulated, human HFSCs showed a clear increase in proliferation, indicating that autophagy enhances the regenerative activity of human stem cells just as it does in animal models. Even more telling, follicles exposed to autophagy activators exhibited an extended anagen phase, suggesting that autophagy not only “wakes” HFSCs but also helps sustain their activity over a longer portion of the hair cycle. [43]

One of the most striking findings was autophagy’s ability to rejuvenate HFSC properties. After activation, stem cells displayed characteristics more typical of younger, more competent HFSCs—evidence that autophagy may help restore intrinsic regenerative potential rather than merely boosting short-term proliferation.

Its ability to restore youthful stem-cell function hints at a broader regenerative potential, positioning autophagy modulation as a promising avenue for therapeutic development.

By demonstrating that human follicles respond to autophagy in nearly the same way as mouse follicles, the study bridges the gap between basic mechanistic biology and translational relevance.

These findings reinforce a central theme emerging across the research: autophagy’s role in HFSC activation and follicle cycling is conserved across species.

Its ability to restore youthful stem-cell function hints at a broader regenerative potential, positioning autophagy modulation as a promising avenue for therapeutic development.

Rapamycin Effects on the Hair Follicle Recap—A Regenerative Primer

Across animal studies, human organ cultures, and HFSC-focused experiments, a unifying insight has emerged: rapamycin reactivates the regenerative machinery of aging hair follicles by rebalancing the mTOR–autophagy axis.

By tempering chronically elevated mTORC1 activity—a hallmark of aging cells—rapamycin restores autophagy, enabling follicles to clear damaged proteins, dysfunctional mitochondria, and inflammatory byproducts that accumulate over time.

For hair biology, this restoration has several downstream consequences:

- HFSCs activate more reliably, supporting earlier and more robust anagen entry.

- The follicular microenvironment becomes less inflammatory, reducing signals that suppress stem-cell behavior.

- Senescent cells and their secretory profiles diminish, relieving local molecular “static” that interferes with regenerative signaling.

- Early fibrotic remodeling is attenuated, helping preserve the structural flexibility the follicle needs to cycle normally.

- The growth phase stabilizes and lengthens, strengthening hair output over successive cycles.

Taken together, these effects frame rapamycin not as a simple hair growth stimulant but as a regenerative primer—a therapy that restores the cellular conditions required for the follicle to respond to other treatments.

Traditional Mechanistic Targets

Before the recent shift toward targeting cellular aging pathways, most hair loss therapies focused on two conventional mechanisms: improving blood flow to the follicle and reducing androgen-driven miniaturization. These approaches remain foundational, but they operate at the tissue and hormonal levels rather than at the level of stem cell renewal.

Enhancing Blood Flow to Support Follicular Metabolism

Healthy follicles depend on a rich microvascular network to deliver oxygen, nutrients, and growth factors necessary to sustain the anagen phase. When local circulation declines, the follicle’s metabolic activity and regenerative capacity falter. Minoxidil, initially developed as an antihypertensive, emerged as the first FDA-approved treatment for androgenetic alopecia after patients reported unexpected hair regrowth [7]. Its primary mechanism is vasodilation: widening blood vessels, increasing scalp blood flow, and improving nutrient delivery to the follicle bulb. By restoring a more supportive metabolic environment, minoxidil helps prolong anagen and delay premature entry into telogen.

Slowing Androgen-Driven Miniaturization

The second long-standing target addresses the hormonal cascade underlying follicular shrinkage. In genetically predisposed individuals, 5α-reductase converts testosterone into dihydrotestosterone (DHT), a potent androgen that binds to follicular receptors and triggers progressive miniaturization—from thick terminal hairs to fine vellus hairs [8].

Finasteride and dutasteride inhibit 5α-reductase, lowering DHT levels within the scalp and slowing or partially reversing this degenerative transition. By reducing the hormonal stress placed on susceptible follicles, these medications help preserve follicular size and density over time.

The Missing Piece: Regenerative Biology

Although minoxidil and finasteride act through distinct pathways—vascular and hormonal—they converge on a common goal: restoring a local environment in which follicles can survive longer and function more effectively. Yet their effects often plateau. Neither therapy directly addresses the cellular aging, metabolic decline, or stem cell exhaustion that accumulate within the follicle over decades.

This limitation has led to a broader reframing in the field: hair loss is not only a hormonal condition or a vascular one, but also a regenerative disorder shaped by declining stem cell activity and impaired autophagy. As molecular biology has advanced, it has become clear that pathways long associated with organismal aging—such as mTOR signaling—also govern the behavior of hair follicle stem cells.

These insights lay the foundation for next-generation, multi-mechanistic protocols that pair the established benefits of finasteride and minoxidil with emerging agents like rapamycin, which directly target the aging pathways that limit follicular renewal.

Minoxidil: Vascular and Growth Stimulation

First introduced as an antihypertensive medication in the 1970s, due to its vasodilatory properties, minoxidil was the first FDA-approved drug for AGA [8]. Minoxidil is now used worldwide for various hair loss conditions. Minoxidil increases blood flow to hair follicles by activating potassium channels on the smooth muscles of the peripheral artery, providing crucial nutrients and oxygen which enable hair follicles to maintain or even recover capacity for healthy growth [7]. Minoxidil has been shown to increase expression of vascular endothelial growth factor as much as 52% compared with controls [22,23]. Minoxidil can extend the anagen phase, but primarily enhances follicle function through direct vascular and cellular action.

Minoxidil is FDA-approved as a topical at 2% and 5% concentrations [1]. For males, the most common concentration used is 5%. Minoxidil takes several months to produce changes in hair thickness and growth. Studies have found that both the 2% and 5% formulations have shown a significant difference in hair growth versus placebo at 6 months, 1 year, and 5 years [8]. Meta-analysis showed that topical minoxidil increased hair follicle density mean differences of 8.11 hairs/cm2 and 14.90 hairs/cm2 associated with the 2% and 5% minoxidil treatments, respectively, compared to the placebo group [20]. There are some concentrations available as high as 8-15%, but while they can be effective, they are also more likely to increase propensity for local side effects like irritation, and lack FDA approval [8].

Finasteride: Hormonal Correction

Finasteride blocks production of the hormone dihydrotestosterone (DHT), curbing a key driver of follicle shrinkage and loss in androgenetic alopecia [8]. By reducing DHT levels, finasteride helps preserve existing hair and can even reverse some loss, but maximum efficacy often requires combination therapy. Oral finasteride is FDA approved; however, convincing data pertaining to topical finasteride as treatment for hair regrowth were first published by Mazzarella et al. in 1997 in a placebo-controlled trial [16].

A recent phase III randomized, controlled clinical trial of over 450 participants reported a 0.25% finasteride solution significantly improves hair count compared with placebo in patients with MPHL despite maintaining relatively stable serum DHT concentrations [17]. Furthermore, it was found to be well tolerated, particularly in comparison with its oral formulation [17]. Peak plasma finasteride concentrations were >100 times lower with topical versus oral finasteride. In addition, the mean DHT concentration was lower (34.5 vs. 55.6%), with topical vs. oral finasteride.

The researchers concluded there are less systemic adverse reactions of a sexual nature related to a decrease in DHT with topical finasteride [17]. Recent study data support topical finasteride for improved hair count similar to that of oral finasteride, but with markedly lower systemic exposure and less impact on serum DHT concentrations.

Why not Dutasteride?

Dutasteride is an inhibitor of 5-alpha-reductase, like finasteride. Although off-label dutasteride use is associated with positive results, finasteride remains the preferred option because finasteride has FDA approval specifically for androgenetic alopecia. Dutasteride is more potent in blocking both type I and type II isoenzymes, yet lacks FDA approval for hair loss. Dutasteride at a dose of 0.5 mg/d can reduce serum DHT levels by approximately 92%, while finasteride at 5 mg/d can reduce serum DHT levels by approximately 73% [18]. Although dutasteride is a promising therapeutic option, it has fewer large, long-term safety and efficacy studies compared to finasteride, especially in female participant groups [19]. Finally, the broad inhibition of type I and type II 5-alpha-reductase isozymes by dutasteride may increase the risk of side effects without providing clear hair preservation superiority. Finasteride’s FDA approval for hair loss treatment and combination therapy data in humans [21] make it a current best fit for maximizing evidence-based benefit and minimizing risk.

Why Rapamycin Enhances the Effectiveness of Traditional Therapies

Modern research makes one point increasingly clear: no single pathway explains hair loss, and no single therapy fully restores follicular health. AGA emerges from the intersection of hormonal stress, microvascular compromise, stem-cell dysfunction, cellular senescence, and early fibrotic remodeling. Addressing only one of these layers may slow progression, but it rarely restores the regenerative potential needed for meaningful, sustained regrowth.

This is where a multi-mechanistic approach becomes essential. Rapamycin, finasteride, and minoxidil—three agents with distinct biological targets—collectively map onto the core processes that govern follicle survival and renewal. Their mechanisms do not overlap; they interlock.

Traditional treatments such as finasteride and minoxidil target two critical—but distinct—axes of follicle biology:

- Finasteride reduces androgenic pressure, slowing the miniaturization process.

- Minoxidil improves vascular perfusion and metabolic support, enhancing follicular nutrient and oxygen delivery.

Both are effective, yet both assume that the follicle retains enough underlying regenerative capacity to respond. In long-standing AGA, that assumption often breaks down: HFSCs become sluggish, senescent cells accumulate, autophagy declines, and fibrotic tissue begins to encroach around the follicle, physically and biochemically constraining its ability to expand and re-enter anagen.

This is precisely where rapamycin becomes synergistic.

By restoring autophagy and reducing senescence-associated signaling, rapamycin helps clear damaged cellular components and early fibrotic changes, softening and rejuvenating the follicular niche. A healthier microenvironment allows:

- Minoxidil’s vasodilatory effects to better reach and support the follicle

- Finasteride’s reduction of DHT burden to yield more pronounced structural recovery

- HFSCs to respond more vigorously to pro-growth cues

In short, rapamycin reconditions the terrain, making follicles more receptive to the vascular and hormonal benefits provided by existing therapies.

This sets the stage for a next-generation treatment paradigm—one that simultaneously targets:

- Hormonal stress (finasteride/dutasteride)

- Vascular and metabolic support (minoxidil)

- Cellular and microenvironmental rejuvenation (rapamycin)

A regenerative approach in which each therapy reinforces the others.

Novel Synergy: Rapamycin + Minoxidil + Finasteride

Hair regrowth data from randomized controlled trials suggest results are enhanced with combination interventions as opposed to monotherapy for either minoxidil or finasteride alone [21,23,24,25,26]. The collective data are promising, pointing to the power of combining rapamycin, minoxidil, and finasteride, particularly when topical rapamycin is used as a priming agent. Rapamycin is mechanistically poised to enhance cellular uptake and responsiveness to finasteride and minoxidil by reducing follicular inflammation [11], activating stem cells [13], and reversing cellular aging [15]. Rapamycin priming creates a more receptive microenvironment for the subsequent synergistic actions of both finasteride and minoxidil.

Safety, Administration, and Practical Considerations

There are only two US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drugs for the condition: topical minoxidil and oral finasteride [8]. Topical formulation of rapamycin is favored for hair treatments due to targeted delivery at the local hair follicle. Minoxidil's side effects are usually mild and limited to local irritation [8]. Finasteride’s systemic side effects (sexual dysfunction, mood changes) can be minimized by topical use [17]. Rapamycin’s topical use has a favorable safety profile in published long term studies [27] for facial skin application. There are no data related to local side effects or adverse events for topical rapamycin for hair regrowth in available rodent studies [11], human trial data is needed in this area for safety and practical purposes.

Multiple research studies and reviews indicate microneedling is an effective way to enhance the efficacy of topical hair loss treatments [1,4,29]. A 2013 randomized, blinded, study reported microneedling enhanced the results compared with topical application of minoxidil twice daily. In the microneedling group, 82% of patients reported more than 50% improvement, versus only 4.5% of patients in the minoxidil only group [28]. Several theories regarding the mechanistic impact of microneedling have been proposed, including the induction of Wnt proteins, signaling to hair follicle stem cells, increased blood flow to the hair follicles, increased scalp absorption and metabolism of topical treatments [29]. Various protocols exist for microneedling; the best results are associated with once weekly,prior to application of the hair-loss topical solution. Microneedling after application is less common and increases the chances for irritation or systemic absorption, which may increase the likelihood of less desirable side effects.

Lifestyle Factors

While pharmacological and topical therapies offer enhanced potency for hair loss treatment, lifestyle interventions inherently enhance outcomes and may slow hair loss progression. Factors such as nutrient-rich diets, regular physical activity, stress management, and good sleep hygiene can positively influence hair follicle health [4]. Emerging evidence also links poor sleep, stress, inflammation, nutrition, and hormonal dysregulation to accelerated or advanced hair loss.

5 Lifestyle Factors Associated with Hair Loss:

1. Chronic Stress and Poor Sleep

Chronic stress and poor sleep can commence or accelerate hair loss. A case-control study compared twenty-five healthy controls with twenty-five participants experiencing hair loss. Based on this study, the authors concluded that high stress may increase hair loss 11-fold, particularly in women [4,33]. Ketoconazole, an antifungal cortisol inhibitor, has shown some promise as an alternative or adjuvant to traditional therapies [4,8].

2. Inadequate Nutrition or Deficiencies

Hair loss is influenced by nutrition related to total energy intake as well as dietary protein intake, fatty acids, vitamins (A, B, D, E), and minerals (iron, zinc, selenium) [4,8]. Routine (quarterly) food logging, including nutrition analysis, to assess for habitual energy and nutrient intake, can aid in identifying or addressing possible inadequacies.

3. Inflammation

Human data report elevated immune and inflammation markers, including eosinophilic infiltration and immunoglobulin (Ig)E levels among patients with diffuse alopecia [30,31].

4. Thyroid Hormone Levels

As such, both deficient and excessive levels of thyroid hormones can contribute to anagen to telogen transition and hair loss [4].

5. Estrogen to Testosterone Ratio

Research suggests the estrogen to testosterone ratio provides greater value than either hormone in isolation, which may further explain why sex hormone concentrations often fail to correlate with reported alopecia symptoms [32].

In addition to healthy lifestyle habit inputs, reducing exposure to certain medications [34], harsh cosmetic treatments or environmental toxins, including heavy metals [4], has been shown to support hair follicle health and contribute to maximizing therapeutic action of pharmacological agents such as rapamycin, minoxidil, and finasteride.

Lab Markers to Track

Various types of alopecia, including AGA, result from disruption of the hair cycle, specifically premature transitions from anagen to telogen due to multiple influences, including hormonal shifts, inflammation, stress, nutritional deficits, and medications [4]. Given this multifactorial etiology, a holistic strategy incorporating laboratory assessments is helpful in identifying contributing factors and guiding personalized treatment through lifestyle and medications.

Key Laboratory Assessments

- Complete Blood Count (CBC), Iron, and Ferritin Levels. These tests help identify anemia or iron deficiency, both of which are common contributors to telogen effluvium and diffuse thinning. Iron and ferritin levels are tightly linked with hemoglobin and red blood cell health. In addition, it is theorized that iron, a cofactor for a rate-limiting enzyme in DNA synthesis, is important to supporting rapidly dividing cells, like hair follicles [4]. Low iron or ferritin status not only reduces oxygen-carrying capacity of red blood cells. It may also lead to decreased cell turnover, decreased hair follicle health, and loss of hair.

- Thyroid Function Tests (TSH, T3, T4). Hypo- or hyperthyroid dysregulation can impair follicular cycling, making evaluation of thyroid hormones a routine part of hair loss lab monitoring [35]. Research suggests T3 and T4 alter human hair follicle growth and support the claim that the deficiency of thyroid hormones in hypothyroid individuals directly plays a role in hair loss [4].

- Sex Hormone Profiles. For suspected AGA or endocrine-related alopecia, related to polycystic ovary syndrome, measurement of androgens (testosterone, DHT), and estrogens can help to uncover hormonal contributions and provide potential avenues for treatment [35].

- Vitamin and Micronutrient Panels. Deficiencies in vitamin D, B12, zinc, and other micronutrients have been implicated in hair loss and can be revealed through lab tests [4]. Known deficiencies are commonly addressed through dietary changes or targeted supplementation.

- Inflammatory Markers. Screening for inflammatory markers like c-reactive protein (CRP) or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) can also provide some advanced insight into potential causal or contributing factors in hair loss. Chronic or systemic inflammatory disorders can cause diffuse hair loss, characterized by premature progression from anagen to telogen phases, signaling lower growth rate and shedding [4].

Conclusion

Taken together, the convergence of mouse experiments, human organ culture data, and HFSC-focused studies reveals a coherent biological story: aging hair follicles lose their regenerative capacity not simply because of hormonal shifts or impaired blood flow, but because stem-cell function, autophagy, and cellular homeostasis deteriorate over time.

Rapamycin directly targets this deeper layer of biology, restoring the metabolic flexibility and damage-clearance pathways that HFSCs require to re-enter anagen. When combined with finasteride—reducing androgenic pressure—and minoxidil—enhancing vascular and metabolic support—the result is a synergistic protocol capable of addressing the multifactorial nature of hair loss.

Lifestyle practices and biomarker monitoring further reinforce these interventions, helping support the physiological conditions necessary for follicular renewal.

The emerging evidence positions autophagy modulation, and rapamycin in particular, as a promising frontier in hair regeneration—one that shifts the field from symptomatic treatment toward true rejuvenation of the follicle’s regenerative machinery.

- Kim, J., Song, S. Y., & Sung, J. H. (2025). Recent Advances in Drug Development for Hair Loss. International journal of molecular sciences, 26(8), 3461. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26083461

- Schielein, M. C., Tizek, L., Ziehfreund, S., Sommer, R., Biedermann, T., & Zink, A. (2020). Stigmatization caused by hair loss - a systematic literature review. Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft = Journal of the German Society of Dermatology : JDDG, 18(12), 1357–1368. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddg.14234

- Callander, J., & Yesudian, P. D. (2018). Nosological Nightmare and Etiological Enigma: A History of Alopecia Areata. International journal of trichology, 10(3), 140–141. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijt.ijt_23_18

- Natarelli, N., Gahoonia, N., & Sivamani, R. K. (2023). Integrative and Mechanistic Approach to the Hair Growth Cycle and Hair Loss. Journal of clinical medicine, 12(3), 893. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12030893

- Harrison, S., & Bergfeld, W. (2009). Diffuse hair loss: its triggers and management. Cleveland Clinic journal of medicine, 76(6), 361–367. https://doi.org/10.3949/ccjm.76a.08080

- Mohamed, N. E., Soltan, M. R., Galal, S. A., El Sayed, H. S., Hassan, H. M., & Khatery, B. H. (2023). Female Pattern Hair Loss and Negative Psychological Impact: Possible Role of Brain-derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF). Dermatology practical & conceptual, 13(3), e2023139. https://doi.org/10.5826/dpc.1303a139

- Messenger, A. G., & Rundegren, J. (2004). Minoxidil: mechanisms of action on hair growth. The British journal of dermatology, 150(2), 186–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05785.x

- Devjani, S., Ezemma, O., Kelley, K. J., Stratton, E., & Senna, M. (2023). Androgenetic Alopecia: Therapy Update. Drugs, 83(8), 701–715. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-023-01880-x

- Schneider, M. R., Schmidt-Ullrich, R., & Paus, R. (2009). The hair follicle as a dynamic miniorgan. Current biology, 19(3), R132-R142.

- Nguyen, T. T., Le, T. N. H., Nguyen, N. N., Yook, S., Ryu, D., Orive, G., ... & Jeong, J. H. (2025). Low-dose rapamycin microdepots promote hair regrowth via autophagy modulation. Journal of Pharmaceutical Investigation, 1-10.

- Suzuki, T., Chéret, J., Scala, F. D., Akhundlu, A., Gherardini, J., Demetrius, D. L., O'Sullivan, J. D. B., Kuka Epstein, G., Bauman, A. J., Demetriades, C., & Paus, R. (2023). mTORC1 activity negatively regulates human hair follicle growth and pigmentation. EMBO reports, 24(7), e56574. https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.202256574

- Gomez-Gomez, T., Linowiecka, K., Hartoyo, M. A., Buchbinder, D. H., Vattigunta, M., Paulaitis, A., ... & Paus, R. (2025). 0895 Combined topical rapamycin and melatonin improve biomarkers of aging/senescence in aged human scalp skin ex vivo. Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 145(8), S155.

- Chai, M., Jiang, M., Vergnes, L., Fu, X., de Barros, S. C., Doan, N. B., Huang, W., Chu, J., Jiao, J., Herschman, H., Crooks, G. M., Reue, K., & Huang, J. (2019). Stimulation of Hair Growth by Small Molecules that Activate Autophagy. Cell reports, 27(12), 3413–3421.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2019.05.070

- Shrestha, M., Nguyen, T. T., Kausar, R., Chaudhary, D., Puspitasari, I. F., Jiang, H. L., Kim, H. S., Yook, S., & Jeong, J. H. (2025). Enhancing hair regrowth using rapamycin-primed mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes. Theranostics, 15(14), 6938–6956. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.107659

- Chen, S., Wang, W., Tan, H. Y., Lu, Y., Li, Z., Qu, Y., Wang, N., & Wang, D. (2021). Role of Autophagy in the Maintenance of Stemness in Adult Stem Cells: A Disease-Relevant Mechanism of Action. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology, 9, 715200. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2021.715200

- Mazzarella, G. F., Loconsole, G. F., Cammisa, G. A., Mastrolonardo, G. M., & Vena, G. A. (1997). Topical finasteride in the treatment of androgenic alopecia. Preliminary evaluations after a 16-month therapy course. Journal of dermatological treatment, 8(3), 189-192.

- Piraccini, B. M., Blume-Peytavi, U., Scarci, F., Jansat, J. M., Falqués, M., Otero, R., Tamarit, M. L., Galván, J., Tebbs, V., Massana, E., & Topical Finasteride Study Group (2022). Efficacy and safety of topical finasteride spray solution for male androgenetic alopecia: a phase III, randomized, controlled clinical trial. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV, 36(2), 286–294. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.17738

- Ding, Y., Wang, C., Bi, L., Du, Y., Lu, C., Zhao, M., & Fan, W. (2024). Dutasteride for the Treatment of Androgenetic Alopecia: An Updated Review. Dermatology (Basel, Switzerland), 240(5-6), 833–843. https://doi.org/10.1159/000541395

- Almudimeegh, A., AlMutairi, H., AlTassan, F., AlQuraishi, Y., & Nagshabandi, K. N. (2024). Comparison between dutasteride and finasteride in hair regrowth and reversal of miniaturization in male and female androgenetic alopecia: a systematic review. Dermatology reports, 16(4), 9909. https://doi.org/10.4081/dr.2024.9909

- Adil, A., & Godwin, M. (2017). The effectiveness of treatments for androgenetic alopecia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 77(1), 136–141.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2017.02.054

- Rossi, A., & Caro, G. (2024). Efficacy of the association of topical minoxidil and topical finasteride compared to their use in monotherapy in men with androgenetic alopecia: A prospective, randomized, controlled, assessor blinded, 3-arm, pilot trial. Journal of cosmetic dermatology, 23(2), 502–509. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.15953

- Abdulhussein Kawen A. (2025). Effects of oral minoxidil on serum VEGF and hair regrowth in androgenetic alopecia. Acta dermatovenerologica Alpina, Pannonica, et Adriatica, 34(1), 7–12.

- Suchonwanit, P., Srisuwanwattana, P., Chalermroj, N., & Khunkhet, S. (2018). A randomized, double-blind controlled study of the efficacy and safety of topical solution of 0.25% finasteride admixed with 3% minoxidil vs. 3% minoxidil solution in the treatment of male androgenetic alopecia. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV, 32(12), 2257–2263. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.15171

- Tanglertsampan C. (2012). Efficacy and safety of 3% minoxidil versus combined 3% minoxidil / 0.1% finasteride in male pattern hair loss: a randomized, double-blind, comparative study. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand = Chotmaihet thangphaet, 95(10), 1312–1316.

- Khandpur, S., Suman, M., & Reddy, B. S. (2002). Comparative efficacy of various treatment regimens for androgenetic alopecia in men. The Journal of dermatology, 29(8), 489–498. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1346-8138.2002.tb00314.x

- Gupta, A. K., Bamimore, M. A., Williams, G., & Talukder, M. (2025). Comparative Efficacy of Minoxidil and 5-Alpha Reductase Inhibitors Monotherapy for Male Pattern Hair Loss: Network Meta-Analysis Study of Current Empirical Evidence. Journal of cosmetic dermatology, 24(7), e70320. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.70320

- Wheless, M. C., Takwi, A. A., Almoazen, H., & Wheless, J. W. (2019). Long-Term Exposure and Safety of a Novel Topical Rapamycin Cream for the Treatment of Facial Angiofibromas in Tuberous Sclerosis Complex: Results From a Single-Center, Open-Label Trial. Child neurology open, 6, 2329048X19835047. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329048X19835047

- Dhurat, R., Sukesh, M., Avhad, G., Dandale, A., Pal, A., & Pund, P. (2013). A randomized evaluator blinded study of effect of microneedling in androgenetic alopecia: a pilot study. International journal of trichology, 5(1), 6–11. https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-7753.114700

- Abdi, P., Awad, C., Anthony, M. R., Farkouh, C., Kenny, B., Maibach, H. I., & Ogunyemi, B. (2023). Efficacy and safety of combinational therapy using topical minoxidil and microneedling for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of dermatological research, 315(10), 2775–2785. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-023-02688-1

- Zhao, Y., Zhang, B., Caulloo, S., Chen, X., Li, Y., & Zhang, X. (2012). Diffuse alopecia areata is associated with intense inflammatory infiltration and CD8+ T cells in hair loss regions and an increase in serum IgE level. Indian journal of dermatology, venereology and leprology, 78(6), 709–714. https://doi.org/10.4103/0378-6323.102361

- Zhang, B., Zhao, Y., Cai, Z., Caulloo, S., McElwee, K. J., Li, Y., Chen, X., Yu, M., Yang, J., Chen, W., Tang, X., & Zhang, X. (2013). Early stage alopecia areata is associated with inflammation in the upper dermis and damage to the hair follicle infundibulum. The Australasian journal of dermatology, 54(3), 184–191. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajd.12065

- Kozicka, K., Łukasik, A., Pastuszczak, M., Jaworek, A., Spałkowska, M., Kłosowicz, A., Dyduch, G., & Wojas-Pelc, A. (2020). Is hormone testing worthwhile in patients with female pattern hair loss?. Polski merkuriusz lekarski : organ Polskiego Towarzystwa Lekarskiego, 48(287), 323–326.

- York, J., Nicholson, T., Minors, P., & Duncan, D. F. (1998). Stressful life events and loss of hair among adult women, a case-control study. Psychological reports, 82(3 Pt 1), 1044–1046. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1998.82.3.1044

- Alhanshali, L., Buontempo, M., Shapiro, J., & Lo Sicco, K. (2023). Medication-induced hair loss: An update. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 89(2S), S20–S28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2023.04.022

- Owecka, B., Tomaszewska, A., Dobrzeniecki, K., & Owecki, M. (2024). The Hormonal Background of Hair Loss in Non-Scarring Alopecias. Biomedicines, 12(3), 513. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12030513

- Millar SE. Molecular mechanisms regulating hair follicle development. J Invest Dermatol. 2002 Feb;118(2):216-25. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01670.x. PMID: 11841536. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11841536/

- Wilson C, Cotsarelis G, Wei ZG, Fryer E, Margolis-Fryer J, Ostead M, Tokarek R, Sun TT, Lavker RM. Cells within the bulge region of mouse hair follicle transiently proliferate during early anagen: heterogeneity and functional differences of various hair cycles. Differentiation. 1994 Jan;55(2):127-36. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.1994.5520127.x. PMID: 8143930. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0301468111603320?via%3Dihub

- Botchkarev VA, Kishimoto J. Molecular control of epithelial-mesenchymal interactions during hair follicle cycling. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2003;8(1):46–55. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12894994

- Blanpain C, Lowry WE, Geoghegan A, Polak L, Fuchs E. Self-renewal, multipotency, and the existence of two cell populations within an epithelial stem cell niche. Cell. 2004;118(5):635–48. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15339667

- Randall VA, Hibberts NA, Hamada K. A comparison of the culture and growth of dermal papilla cells from hair follicles from non-balding and balding (androgenetic alopecia) scalp. Br J Dermatol. 1996 Mar;134(3):437-44. PMID: 8731666.

- Lin E, Zhu N, Cai B, Huang K, Lin C. The role of LncRNAs and miRNAs in hair papilla cell senescence and hair follicle regeneration (in Chinese). Chin J Aesth Plast Surg. 2018;29(07):4357+3.

- Bahta AW, Farjo N, Farjo B, Philpott MP. Premature senescence of balding dermal papilla cells in vitro is associated with p16(INK4a) expression. J Invest Dermatol. 2008 May;128(5):1088-94. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701147. Epub 2007 Nov 8. PMID: 17989730. https://www.jidonline.org/article/S0022-202X(15)33852-5/fulltext

- Sun P, Wang Z, Li S, Yin J, Gan Y, Liu S, Lin Z, Wang H, Fan Z, Qu Q, Hu Z, Li K, Miao Y. Autophagy induces hair follicle stem cell activation and hair follicle regeneration by regulating glycolysis. Cell Biosci. 2024 Jan 5;14(1):6. doi: 10.1186/s13578-023-01177-2. PMID: 38183147; PMCID: PMC10770887.

Related studies