Blood Flow to Brain Function: How GLP-1 Therapies May Reduce Dementia Risk

Prefer to listen? Hit play for a conversational, audio‑style summary of this article’s key points.

GLP-1 receptor agonists have emerged as one of the most promising pharmacologic classes for reducing dementia risk, supported by converging evidence from mechanistic studies, large observational cohorts, and early clinical trials.

GLP-1 medications act on both upstream and downstream drivers of neurodegeneration, improving insulin sensitivity, vascular function, and mitochondrial efficiency while also influencing amyloid, tau, neuroinflammation, and synaptic health.

The vascular hypometabolism hypothesis reframes dementia as a disorder of energy delivery, where chronic reductions in cerebral blood flow and glucose utilization precede and likely contribute to amyloid and tau pathology.

GLP-1s are uniquely suited to address brain energy crisis, improving cerebral perfusion, endothelial function, and metabolic precision in brain regions most vulnerable to cognitive decline.

Despite strong biological rationale and epidemiologic data, oral semaglutide did not demonstrate clinical benefit in the EVOKE and EVOKE+ trials, underscoring the complexity of translating metabolic repair into cognitive outcomes in established Alzheimer’s disease.

EVOKE+ nevertheless showed favorable shifts in Alzheimer’s-related biomarkers, indicating meaningful biological engagement and sharpening the field’s focus toward earlier intervention, better patient selection, and improved brain delivery.

GLP-1s are cornerstone metabolic therapies, most effective when combined with lifestyle interventions and complementary geroprotective strategies that support vascular health, mitochondrial function, and dementia prevention.

Introduction

Dementia and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) have long been framed as primarily neurological disorders, but a growing body of evidence suggests they are deeply intertwined with metabolic, vascular, and inflammatory dysfunction. Type 2 diabetes and obesity dramatically increase the risk of dementia by up to 60%, accelerating amyloid pathology, cerebrovascular damage, and insulin resistance in the brain, sometimes described as “type 3 diabetes” [1].

GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs), originally developed for glycemic control, sit at the intersection of critical pathways that contribute to dementia etiology. Beyond weight loss, GLP-1 medications improve insulin signaling, reduce systemic and neuroinflammation, enhance mitochondrial efficiency, and exert direct effects on neurons and glial cells to maintain neurological cell health [2]. Over the past five years, this convergence has driven extraordinary optimism that GLP-1s might meaningfully diminish dementia risk and perhaps even alter disease progression trajectory to a greater extent than other common diabetes medications [3].

The Vascular Hypometabolism Hypothesis: Reframing Dementia as an Energy and Delivery Problem

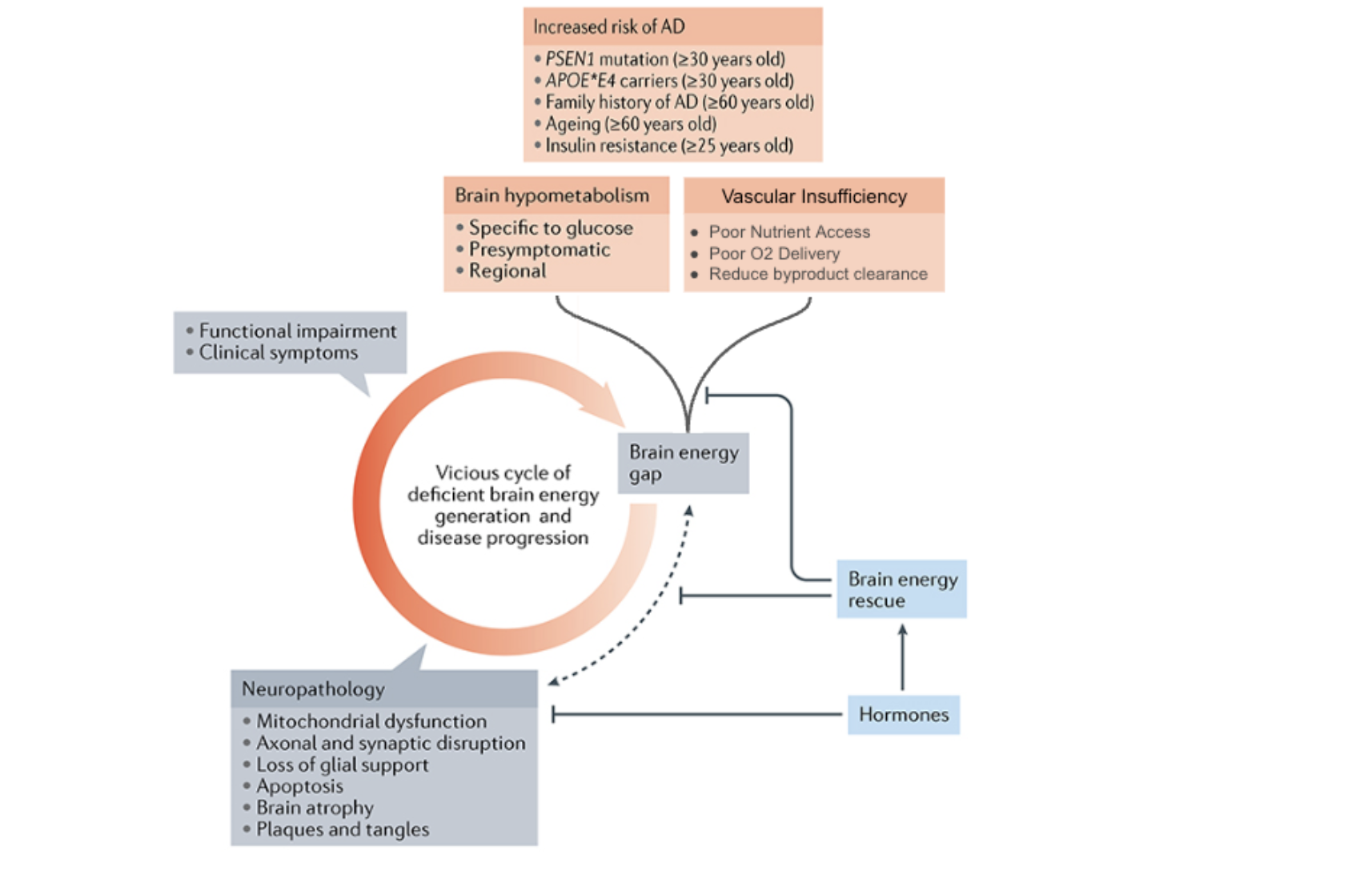

A growing body of evidence suggests that dementia and Alzheimer’s disease are driven less by isolated protein aggregates and more by a chronic failure of blood flow, nutrient delivery, and metabolic precision in the brain, a framework often described as the vascular hypometabolism hypothesis [4, 5]. The brain accounts for roughly 20% of resting energy expenditure, yet it has a limited capacity for energy storage [4, 5, 6]. Even modest, sustained impairments in cerebral blood flow, glucose delivery, insulin signaling, or mitochondrial efficiency can create a long-term neuronal energy deficit. Over time, this energy shortfall sets off a cascade of downstream effects: synaptic dysfunction, impaired protein clearance, neuroinflammation, and ultimately the accumulation of amyloid-β and tau pathology [5].

Even modest, sustained impairments in cerebral blood flow, glucose delivery, insulin signaling, or mitochondrial efficiency can create a long-term neuronal energy deficit. Over time, this energy shortfall sets off a cascade of downstream effects: synaptic dysfunction, impaired protein clearance, neuroinflammation, and ultimately the accumulation of amyloid-β and tau pathology

Importantly, imaging and metabolic studies consistently show that reductions in cerebral glucose metabolism and perfusion precede cognitive symptoms by years, often decades [8]. Individuals with insulin resistance, visceral adiposity, hypertension, and endothelial dysfunction exhibit early declines in cerebral blood flow and metabolic flexibility, long before overt dementia emerges. According to the vascular hypometabolism hypothesis, amyloid plaques and tau tangles may be consequences rather than root causes of biological stress signals arising when neurons do not receive sufficient blood flow and are under-nourished. Amyloid and tau may be better understood as smoke, not fire, signals of metabolic stress instead of its original cause.

...amyloid plaques and tau tangles may be consequences rather than root causes of biological stress signals arising when neurons do not receive sufficient blood flow and are under-nourished. Amyloid and tau may be better understood as smoke, not fire, signals of metabolic stress instead of its original cause.

Brain Energy Gap

Leading researchers in the field of cognitive disease and brain metabolism have described and measured decrements in brain energy production with aging and disease. Dr. Stephen Cunnane’s work describes the role of brain energy rescue in combating neurodegenerative diseases, including dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease [9]. Of note, this brain energy gap is often specifically linked with diminished glucose metabolism. Brain energy deficits stemming from poor glucose metabolism are present before the onset of cognitive decline; this presymptomatic deficit contributes to deteriorating brain structure and function associated with the onset of AD [9,10]. Consequently, providing alternative fuel sources for energy production to alleviate the brain energy gap has improved cognitive performance in randomized human trials [10].

Figure 3. Vascular Hypometabolism Hypothesis Feeds Brain Energy Gap. Hypometabolism in the brain increases risk of Alzheimer disease (AD). Poor blood flow, nutrient access, and oxygen delivery contribute to metabolic challenges and energy crises which can contribute to feed-forward cycle and increased AD disease risk.

In addition to providing alternative fuels for energy production, enhancing insulin sensitivity and boosting brain glucose metabolism are both high priority therapeutic targets for neurodegenerative disease. Alternate fuel substrates, such as ketones, can support cognitive acute performance improvements [11], while recovering insulin sensitivity and the ability to utilize glucose to meet brain energy demands is critical for long term prevention or slowing cognitive decline.

GLP-1 receptor agonists are uniquely positioned to address the upstream problem. GLP-1s improve systemic insulin sensitivity, reduce vascular inflammation, enhance endothelial function, and modestly lower blood pressure collectively improving blood flow and nutrient delivery to the brain [12]. Emerging evidence also suggests GLP-1s increase cerebral blood flow through arteriolar vasodilation and may promote angiogenesis, helping restore metabolic support in vulnerable brain regions [13]. By improving both energy availability and energy precision, GLP-1s help stabilize neuronal metabolism, reduce oxidative stress, and create conditions more conducive to synaptic maintenance and plasticity.

Emerging human data suggest that GLP‑1 receptor agonists may improve central insulin sensitivity and brain glucose handling. GLP-1 and GIP receptors present in the brain offer a direct target for improved metabolic function [14,15]. GLP-1 treatments produce reliable metabolic benefits, such as reduced body mass index and improved total body glucose levels. There are also indications of potential neuroprotective effects on cerebral glucose metabolism and modest increases in blood-brain glucose transport capacity in the brain measured using 18F-FDG PET [16]. Overall, GLP‑1 agonists show central effects on brain regions involved in energy balance and cognition and may act in parallel to, rather than simply downstream of, insulin to modulate neuronal activity and glucose utilization.

Blood Flow Improvements

Through a vascular hypometabolism lens, GLP-1s are not merely weight-loss or glucose-lowering drugs, they are neuro-metabolic stabilizers. GLP-1s aid in correcting the systemic and vascular dysfunction that deprives the brain of fuel, oxygen, and metabolic adaptability. This framing also explains why GLP-1s may be most effective early in the disease continuum, or as part of preventive strategies aimed at preserving cerebral blood flow, metabolic health, and mitochondrial resilience before irreversible neurodegeneration takes hold [14,15].

A growing body of preclinical, imaging, and human observational data suggests that GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) may meaningfully improve cerebral blood flow (CBF), a critical factor in maintaining cognitive function and minimizing dementia risk. Cerebral hypoperfusion is now recognized as an early and independent contributor to cognitive decline, often preceding overt amyloid or tau pathology [17]. GLP-1 receptors are expressed on up to 70% cerebral arterioles [18] and endothelial cells, and experimental models demonstrate that GLP-1 signaling promotes arteriolar vasodilation, improved endothelial nitric oxide signaling, and angiogenic pathways such as VEGF upregulation, all of which enhance nutrient and oxygen delivery to metabolically active brain regions [13,14].

GLP-1RAs reduce inflammation, systemic endothelial function, and modestly improve cerebral perfusion, particularly in individuals with insulin resistance, obesity, or metabolic syndrome [15]. Despite the overwhelming success of GLP-1 medications related to weight loss, GLP-1 therapy is associated with increased cerebral blood flow and reduced small-vessel disease burden, even when controlling for weight loss [15]. This vascular mechanism may help explain why GLP-1RAs consistently show reduced dementia incidence in large observational cohorts, even when effects on amyloid burden or short-term cognition are modest [13,14,15].

By improving cerebral blood flow, GLP-1s enhance glucose and oxygen delivery, support mitochondrial ATP production, and reduce energy insufficiency that promotes synaptic dysfunction, impaired protein clearance, and neuroinflammation [5]. GLP-1 medications stabilize metabolic function and blood flow, addressing upstream drivers of cognitive decline, dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease. GLP-1s are one of the most promising pharmacologic tools for restoring cerebral perfusion and energy production in the brain while simultaneously improving disease risk factors and contributing to measurable changes in healthspan.

The Case for Optimism: Years of Compelling Data

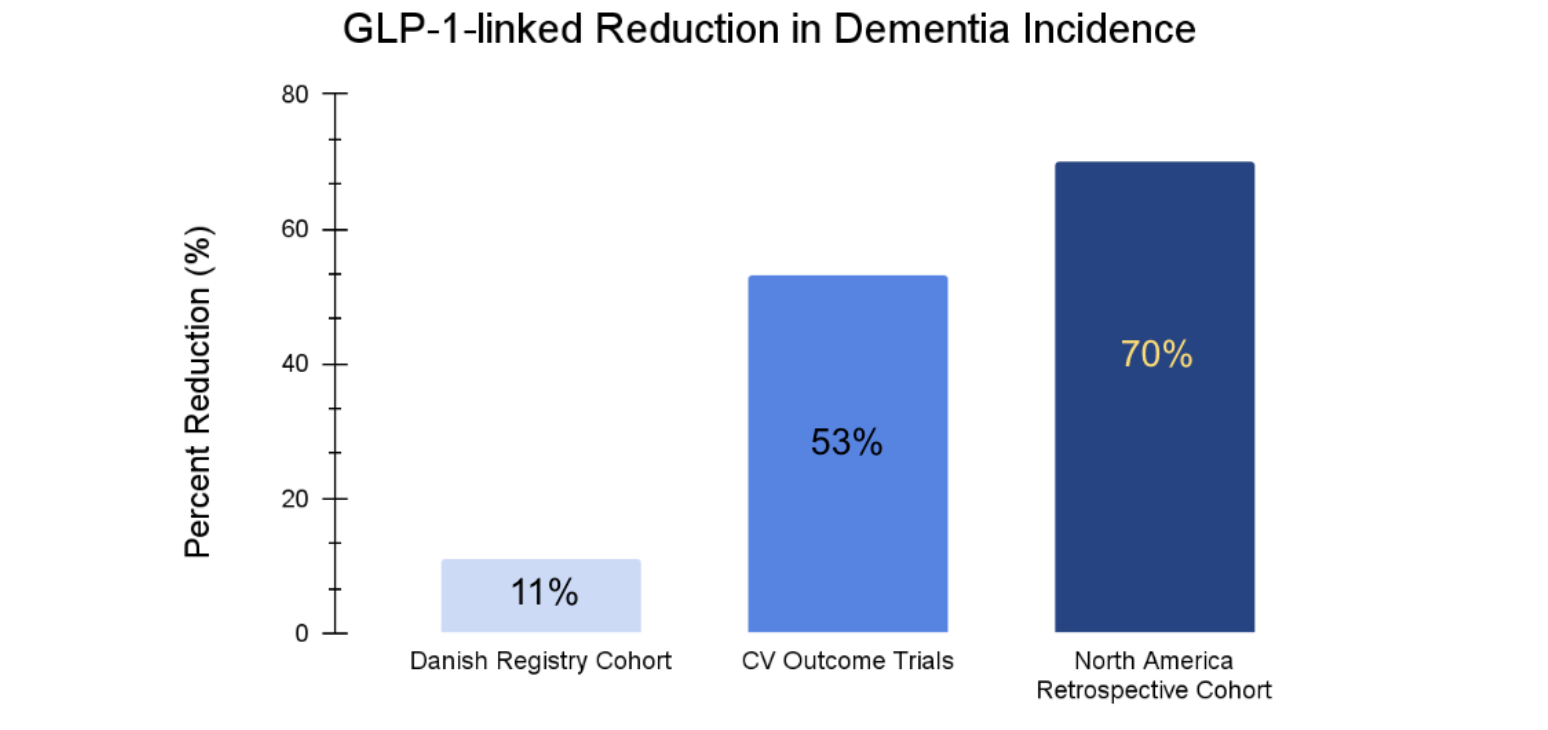

The optimism around GLP-1s and dementia is not speculative, it is data-driven. Large observational studies and post-hoc analyses consistently associate GLP-1RA exposure with lower incidence of dementia in people with type 2 diabetes. Multiple cohorts report hazard ratios in the range of 0.6–0.8, even after adjusting for weight loss and glycemic control [14].

For context, a hazard ratio compares how often an outcome occurs over time between two groups. A value of 1.0 indicates no difference in risk. Values below 1.0 indicate risk reduction. A hazard ratio of 0.7, for example, corresponds to roughly a 30% lower rate of developing dementia during the study period. In epidemiology, effects of this magnitude—especially when observed repeatedly across large populations—are considered clinically meaningful rather than trivial statistical artifacts.

That signal has now appeared across independent datasets. A recent U.S. claims-based analysis found approximately a 33% lower risk of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias among GLP-1 users compared with patients treated with other glucose-lowering therapies [9]. Importantly, these associations persist after accounting for improvements in glycemic control and body weight, suggesting that the observed neuroprotective signal may not be solely attributable to better metabolic management.

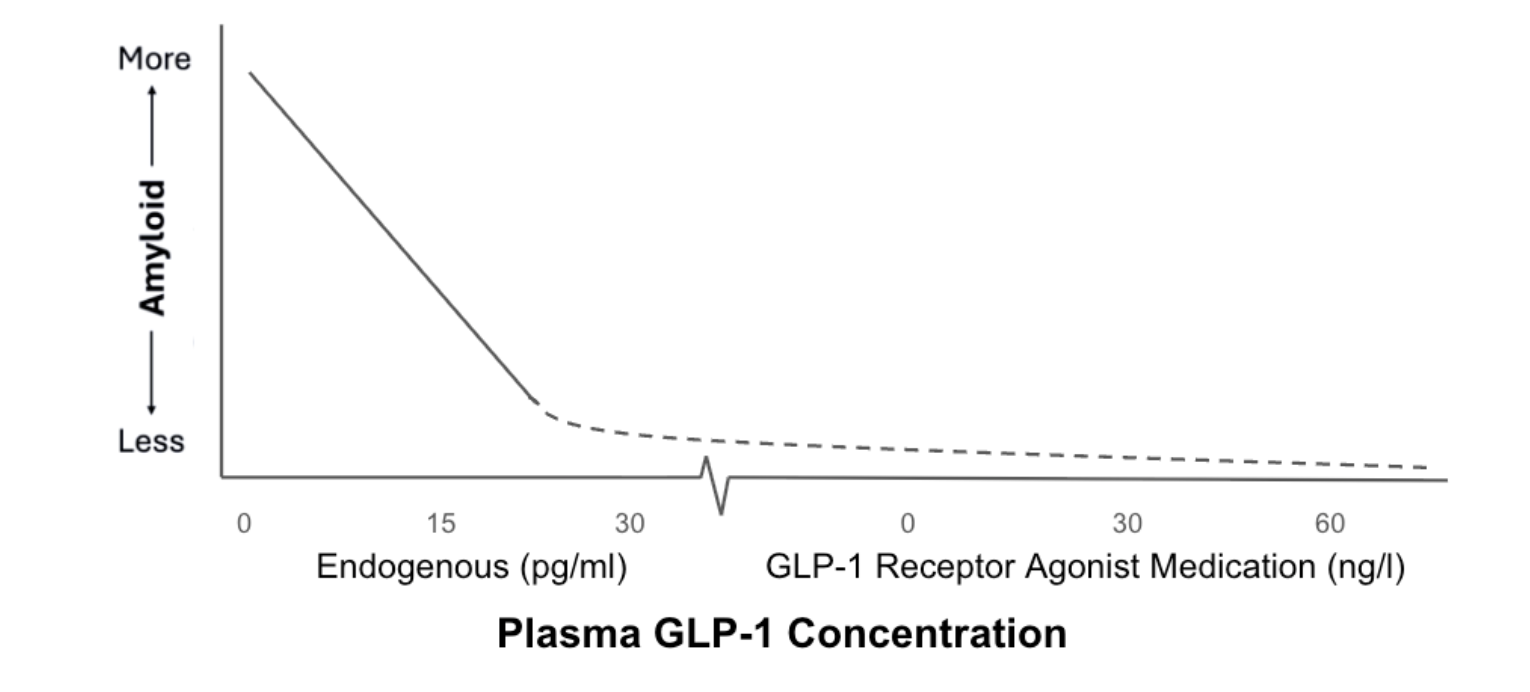

Supporting this epidemiologic signal, large cohort data also suggest an inverse relationship between GLP-1 exposure and a core pathological hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease: the accumulation of amyloid in the brain [32].While observational data cannot establish causality, the convergence of reduced clinical incidence and favorable biomarker associations strengthens the case that GLP-1 signaling may be influencing disease-relevant biology rather than serving as a passive metabolic proxy.

Figure 2. Inverse Relationship Between GLP-1 Concentration and Amyloid Burden. Solid line indicates reduction in amyloid burden associated with higher endogenous GLP-1 concentration (pg/ml). Dotted line suggests plausible asymptotic relationship with exogenous GLP-1 medications that produce concentrations that are 1000x higher (ng/ml).

Large-scale research data, including pooled data from three randomized double-blind placebo-controlled cardiovascular outcome trials, and a nationwide Danish registry-based cohort in over 120,000 patients, suggests GLP-1s reduce the incidence of dementia, especially in patients with type 2 diabetes [19]. Dementia rate was 53% lower in patients randomized to GLP-1 RAs versus placebo from the cardiovascular trials (HR = 0.47). In the Danish registry-based cohort, dementia risk was reduced 11% (HR = 0.89) with yearly increased exposure to GLP-1 RAs. Similarly, a retrospective cohort trial, published in 2025, which included over 295,000 patients from North America, reported GLP‑1RA use was associated with about a 70% lower risk of incident dementia vs non‑use (HR = 0.30), significant even after statistical matching and multivariable adjustments [20]. This consistency across datasets has elevated GLP-1s from metabolic drugs to legitimate neuroprotective candidates.

Figure 3. Dementia Incidence Reduction with GLP-1 Medications. Separate large scale clinical trials totaling over 450,000 participants demonstrate there are significant reductions in dementia incidence for individuals using GLP-1 medications based upon hazard ratio data.

GLP-1s Direct Biological Impact in the Brain

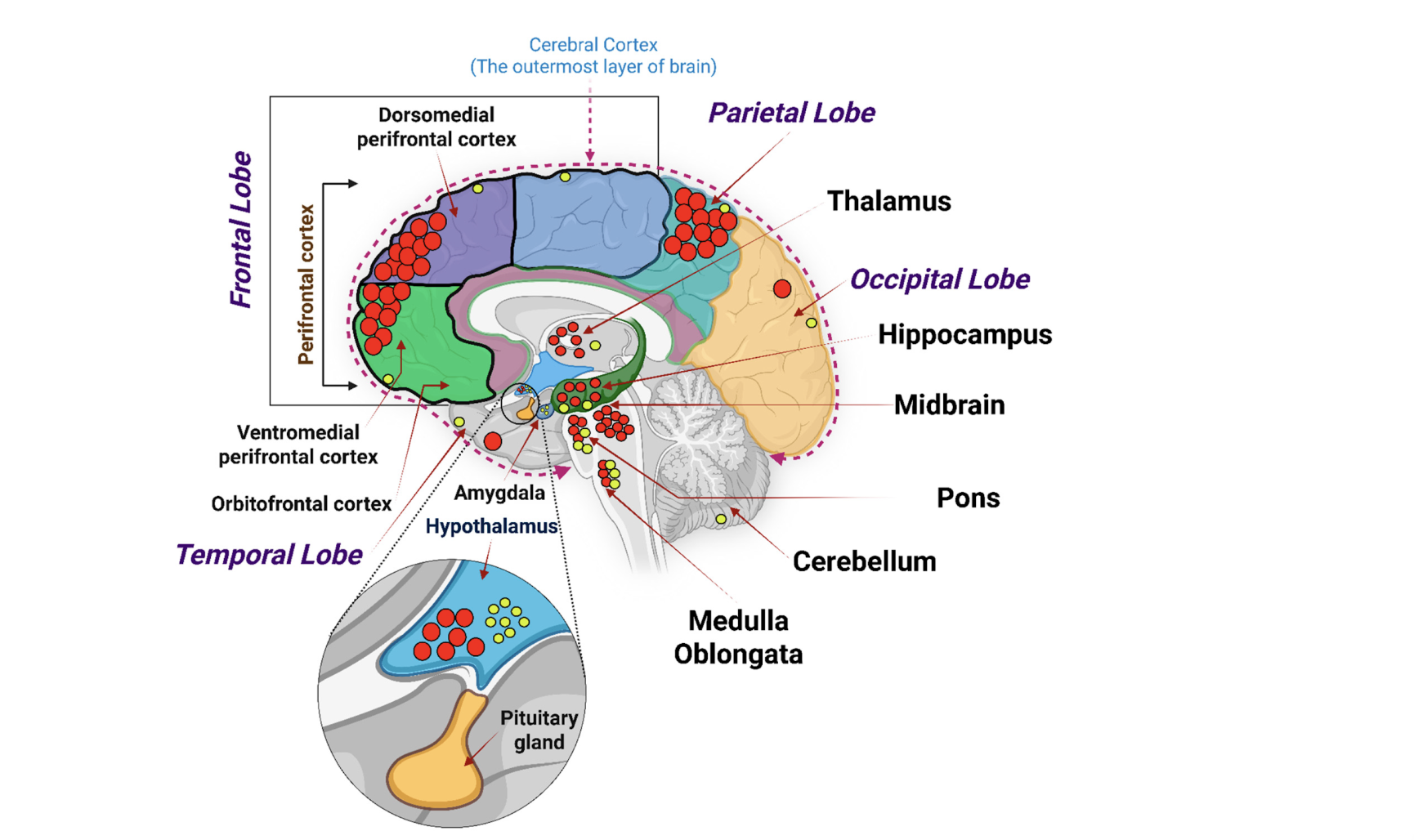

Beyond their systemic metabolic effects, GLP-1 medications exert direct biological actions in the brain through widespread expression of incretin (GLP-1) receptors in regions critical for cognition, including the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, and hypothalamus [14]. These are not passive metabolic relay stations. The hippocampus underpins memory formation, the prefrontal cortex governs executive function and attention, and the hypothalamus integrates energy status with neuroendocrine signaling—functions that are progressively disrupted early in neurodegenerative disease.

Activation of central GLP-1 receptors enhances neuronal insulin signaling, improves glucose uptake, and supports mitochondrial energy production. This is particularly relevant in the aging brain, where insulin resistance and impaired glucose metabolism emerge years before overt cognitive symptoms. Cerebral hypometabolism is one of the earliest detectable features of Alzheimer’s disease, often preceding amyloid deposition or clinical diagnosis. In this context, GLP-1–mediated improvements in brain insulin sensitivity address a foundational energetic deficit rather than a downstream consequence of neurodegeneration [15].

GLP-1 signaling also exerts potent anti-inflammatory effects within the central nervous system. Experimental models show that GLP-1 receptor activation suppresses microglial overactivation and pro-inflammatory cytokine signaling, while restoring diet-induced impairments in brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) pathways [21]. BDNF plays a central role in synaptic maintenance, plasticity, and learning—processes that deteriorate as neuroinflammation and metabolic stress accumulate. Recovery of BDNF signaling therefore represents not just symptom modulation, but preservation of synaptic infrastructure.

Importantly, GLP-1 receptor activation has also been shown to reduce amyloid-β accumulation in experimental models, linking metabolic signaling directly to canonical Alzheimer’s pathology [14]. This suggests that metabolic dysfunction, neuroinflammation, and protein aggregation are not independent processes, but interconnected nodes within the same disease network.

Taken together, the presence and activity of incretin receptors in the brain provide a mechanistic bridge between metabolic health and neurodegeneration. Rather than acting solely through weight loss or peripheral glucose control, GLP-1 therapies engage neural pathways involved in energy regulation, inflammation, synaptic integrity, and protein homeostasis—offering a biologically coherent explanation for their emerging association with preserved cognitive function and reduced dementia risk.

Figure 4. Incretin Receptors mRNA expression in human brain anatomy. Red and yellow circles indicate localized GLP-1 receptor mRNA transcription

Activation of incretin receptors initiates a cascade of neuroprotective effects:

- Improved brain insulin signaling, correcting neuronal energy deficits.

- Reduced amyloid-β accumulation and tau hyperphosphorylation, demonstrated repeatedly in animal models.

- Suppression of neuroinflammation, shifting microglia and astrocytes toward neuroprotective phenotypes.

- Enhanced synaptic plasticity and BDNF signaling, supporting learning and memory.

- Improved cerebral blood flow and vascular function, indirectly reducing vascular contributions to cognitive impairment.

Crucially, several of these effects appear independent of weight loss, strengthening the argument that GLP-1s promote direct neurobiological benefits for brain health and dementia prevention.

GLP-1 Therapeutic Potential

GLP-1 medications are compelling not simply because they influence body weight or glucose control, but because they engage several biological processes that converge on age-related cognitive decline, metabolic dysfunction, and dementia. Existing epidemiologic and mechanistic data support a potential role for GLP-1 receptor agonists in dementia risk reduction, particularly in metabolically vulnerable populations [14,15]. Promising data has fueled some scientific speculation and hypothesis generation that suggests there may be therapeutic and even curative potential for GLP-1s.

That signal has nonetheless fueled scientific speculation and hypothesis generation, including proposals that GLP-1 therapies could exert disease-modifying—and in some theoretical frameworks, even curative—effects in Alzheimer’s disease. In 2024, a provocative review published in the Journal of Clinical Medicine argued that GLP-1 receptor agonists might theoretically “cure” Alzheimer’s disease by targeting dysfunction across all major brain cell populations [22].

The argument rests on the unusually broad distribution of GLP-1 receptors throughout the central nervous system. Neurons, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, microglia, endothelial cells, and pericytes all express GLP-1 receptors, positioning incretin signaling to influence neuronal metabolism, synaptic support, neuroinflammation, myelination, vascular integrity, and blood–brain barrier function [22]. The review also highlighted preclinical evidence that GLP-1 receptor activation can counteract reactive oxygen species and mitigate oxidative cytotoxicity—processes that accelerate cellular injury across multiple neurodegenerative pathways.

Taken together, the paper effectively captured the field’s enthusiasm, framing GLP-1 therapies as uniquely positioned to act across the full pathological spectrum of Alzheimer’s disease rather than targeting a single downstream lesion. Among available agents, dulaglutide (Trulicity) was highlighted for its relatively high brain penetration—reported at approximately 62%—and its ability in experimental models to influence oxidative stress, amyloid handling, and neuronal energy metabolism [22].

While these hypotheses are biologically coherent and mechanistically intriguing, they currently extend beyond what has been demonstrated in human clinical trials. Claims of disease reversal or cure remain speculative. That said, more recent human trial data have begun to provide greater clarity regarding the translational potential of GLP-1 therapies in Alzheimer’s disease, helping to refine which aspects of these theoretical benefits may ultimately prove clinically meaningful.

Recent Clinical Trial Results: EVOKE and EVOKE+

Two recent large-scale, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials, known as EVOKE and EVOKE+ evaluated oral semaglutide (Rybelsus) in patients with early Alzheimer’s disease [23]. Despite high expectations, preliminary data reports indicated that EVOKE and EVOKE+ trials failed to meet their primary cognitive endpoints [24]. Clinically, semaglutide did not slow cognitive decline to a statistically meaningful degree compared with placebo.

When the EVOKE and EVOKE+ trials failed to meet their primary cognitive endpoints, some headlines framed the outcome as a major blow to the idea that GLP-1 medications could meaningfully impact Alzheimer’s disease. As is often the case, a “failure” in science, in reality, did not invalidate a strong GLP-1 hypothesis, rather it improves, or refines, it for follow up investigations.

EVOKE+ demonstrated that high-dose oral semaglutide engaged Alzheimer’s biology, producing favorable shifts in biomarkers of neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation, even though those changes did not translate into measurable clinical benefit over the trial period. That distinction matters. It suggests the drug reached the brain and affected disease-relevant pathways, but that timing, magnitude, delivery, or patient selection were insufficient to overcome established neurodegeneration when used as a stand-alone therapy.

The results of the EVOKE trials suggest:

- Timing matters: GLP-1s may be more effective in prevention or very early disease.

- Patient selection matters: Efficacy is likely higher in insulin-resistant, vascular, or metabolically impaired individuals.

- Dose, delivery, and brain absorption matter: Some GLP-1s are better absorbed and have more potential to improve cognitive endpoints than others

- Combination therapeutics may be required: GLP-1s may need to be paired with lifestyle interventions or complementary neuroprotective agents to produce measurable results in specific disease outcomes.

EVOKE+ demonstrated favorable shifts in Alzheimer’s-related biomarkers, including markers of neurodegeneration and inflammation [24]. In other words, semaglutide engaged Alzheimer’s biology but not strongly enough, or early enough, to translate into clinical benefit as a stand-alone therapy. There are several potential reasons for the reduced magnitude of effects on primary endpoints related to cognitive decline. Perhaps oral semaglutide is not an ideal mode of delivery to achieve measurable improvements in cognitive outcomes, and another variant of GLP-1 medication would be better suited. According to some of the most optimistic research published, dulaglutide has the highest brain uptake [22], and therefore, it may enable more significant positive effects.

Rather than disproving GLP-1s as brain-protective agents, EVOKE sharpened the field’s focus. It has accelerated interest in earlier intervention, vascular health strategies, exploring different GLP-1 formulations, and combination approaches that pair GLP-1s with complementary lifestyle or pharmacological synergists. The takeaway is not that GLP-1s failed, but that Alzheimer’s disease is harder than metabolic disease, and likely requires earlier, smarter, and multi-modal strategies.

Where the Science Stands Today

GLP-1 medications are not Alzheimer’s cures but they are no longer fringe candidates. The weight of evidence supports a role in dementia risk reduction, particularly among individuals with diabetes, obesity, metabolic syndrome, or APOE ε4 risk. The strongest effects likely lie in prevention and early intervention, not disease reversal. Despite exciting mechanistic and theoretical potential in GLP-1s, we lack human evidence at this point that demonstrates curative effects. The next phase of research is already underway: brain-penetrant GLP-1s, intranasal delivery, head-to-head neurocognitive trials, and combination approaches that pair metabolic repair with targeted neurobiology.

Synergistic GLP-1 Combination Strategies

While GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) are emerging as powerful tools for reducing dementia risk, the biology of cognitive decline strongly suggests that no single intervention is sufficient [25]. Dementia and Alzheimer’s disease appear to arise from a chronic brain energy crisis, driven by impaired glucose utilization, insulin resistance, mitochondrial dysfunction, vascular insufficiency, and sustained neuroinflammation. In this context, GLP-1s may function best not as stand-alone therapies, but as central hubs within a broader geroprotective strategy that targets complementary aging pathways.

Rapamycin

Several candidate interventions align naturally with GLP-1 biology. Rapamycin, for example, targets mTOR signaling, a central regulator of growth and metabolism that becomes chronically overactive with age. In experimental models, mTOR inhibition promotes autophagy, enhances cellular stress resistance, and supports vascular health—functions that are progressively impaired in the aging brain.

Conceptually, GLP-1 therapies and rapamycin act on complementary nodes of the same metabolic network. GLP-1 receptor activation enhances insulin signaling, activates AMPK, and suppresses inflammatory cascades, improving cellular energy balance and reducing metabolic stress. Rapamycin, by contrast, dampens excessive anabolic signaling and restores autophagic capacity, facilitating the clearance of damaged proteins and organelles. Together, these interventions may address multiple upstream drivers of neurodegeneration: dysregulated nutrient sensing, chronic inflammation, and impaired cellular maintenance [26].

This complementarity is particularly relevant to cerebrovascular health. Endothelial dysfunction and breakdown of the blood–brain barrier are now recognized as early contributors to cognitive decline, often preceding overt neuronal loss. Both GLP-1 signaling and mTOR modulation have been shown independently to support endothelial function, reduce vascular inflammation, and improve barrier integrity in preclinical models. From a translational perspective, this raises the possibility that combined modulation of these pathways could stabilize the neurovascular unit and preserve cerebral homeostasis.

At present, published human data examining combined GLP-1 and rapamycin therapy are lacking, and any claims of synergy remain hypothetical. Nonetheless, the mechanistic alignment between these pathways provides a biologically plausible rationale for future investigation—particularly in the context of dementia prevention, where upstream metabolic and vascular interventions may offer greater leverage than late-stage amyloid-targeted approaches.

SGLT2 Inhibitors

Similarly, SGLT2 inhibitors offer a distinct but partially overlapping metabolic benefit that may be especially relevant to the energetically vulnerable aging brain. By lowering plasma glucose through renal excretion and modestly increasing circulating ketone availability, SGLT2 inhibitors shift systemic and cerebral energy metabolism away from exclusive dependence on glucose [27].

Ketones provide neurons with an efficient alternative fuel source that bypasses several steps of insulin-dependent glucose metabolism. In the context of neurodegeneration, this may help stabilize neuronal energy production when glucose uptake and utilization are compromised. SGLT2 inhibitors therefore do not merely lower glycemia, but introduce a parallel energetic pathway that may buffer against progressive metabolic failure in vulnerable neural circuits.

When considered alongside GLP-1 therapies, a complementary framework emerges. GLP-1 receptor agonists improve insulin sensitivity, enhance cerebral blood flow, and reduce neuroinflammatory signaling, addressing upstream defects in glucose delivery and utilization. SGLT2 inhibitors, in contrast, expand the brain’s energetic flexibility by increasing access to ketone substrates. Together, this dual strategy may reduce the energetic bottleneck that characterizes early neurodegenerative states.

Observational data suggest that both drug classes are independently associated with lower dementia risk [14, 27]. While these findings do not establish additive or synergistic effects, they raise a biologically plausible hypothesis: that combined metabolic support—improving glucose handling while simultaneously supplying alternative fuels—may outperform either strategy alone. Determining whether this conceptual advantage translates into clinical benefit will require prospective trials specifically designed to assess cognitive and neurodegenerative outcomes.

Near Infrared, Methylene Blue

Beyond pharmaceuticals, mitochondrial-targeted interventions represent a complementary strategy that may amplify GLP-1–mediated benefits, particularly in brain regions that are disproportionately vulnerable to early metabolic failure. Near-infrared (NIR) light therapy, with or without low-dose methylene blue (MB), has been shown in experimental and early clinical contexts to enhance mitochondrial electron transport, improve ATP production, and reduce oxidative stress in neural tissue [28]. These effects target core bioenergetic deficits that emerge early in dementia, including impaired oxidative phosphorylation, regional hypometabolism, and accumulation of reactive oxygen species.

Mitochondrial dysfunction is not uniformly distributed across the brain. Regions such as the hippocampus and posterior cingulate cortex exhibit early declines in mitochondrial efficiency and energy availability, contributing to synaptic failure long before widespread neuronal loss occurs. By improving electron flow through the respiratory chain and reducing redox bottlenecks, NIR and methylene blue may help stabilize neuronal energy production in these metabolically fragile networks.

At present, direct clinical evidence supporting combined use of GLP-1 therapies with NIR or methylene blue in dementia is limited, and claims of additive or synergistic benefit remain hypothetical. Nonetheless, the mechanistic complementarity—spanning vascular delivery, metabolic signaling, and mitochondrial efficiency—offers a biologically plausible rationale for further investigation, particularly in early disease stages where restoring energy balance may yield the greatest protective effect.

Lithium

Lithium, particularly at low, non-psychiatric doses, represents another intriguing adjunct candidate. Recent research suggests that lithium deficiency is a prominent contributor to Alzheimer’s disease incidence [29]. Researchers conclude low dose lithium replacement with amyloid-evading salts is a potential approach to the prevention and treatment of AD [29]. Lithium activates neuroprotective pathways including GSK-3β inhibition, enhanced autophagy, and synaptic resilience, while also modulating inflammation and tau phosphorylation. In the context of GLP-1 therapy, lithium may reinforce downstream neurotrophic and anti-inflammatory signaling, potentially strengthening long-term synaptic maintenance and cognitive resilience.

Lifestyle Habits

Crucially, none of these strategies can substitute for foundational lifestyle interventions. Exercise, sleep, and nutrition remain indispensable for preserving metabolic health and preventing the chronic energy deficits that likely underlie dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Physical activity enhances insulin sensitivity, cerebral blood flow, mitochondrial biogenesis, and neuronal inflammation [30]. Sleep supports glymphatic clearance of metabolic waste, including amyloid-β, and maintains circadian alignment of brain energy use [31]. Nutrition, particularly adequate protein, micronutrients, and metabolic flexibility, ensures the brain is supplied with the substrates required to meet its exceptionally high energy demands [32]. Without these pillars in place, even the most sophisticated pharmacologic or device-based interventions are unlikely to fully succeed.

Taken together, GLP-1s may be best understood not as isolated “anti-dementia drugs,” but as cornerstone geroprotective agents that integrate naturally with other longevity molecules and lifestyle habits. Addressing dementia risk likely requires simultaneous support of metabolism, mitochondria, vascular health, and cellular health with GLP-1s providing a powerful foundation upon which multi-modal brain health strategies can be built.

Conclusion: A Field Maturing, Not Failing

We are now witnessing the scientific maturation story of GLP-1s for longevity. Dementia and Alzheimer's are experiencing a shift in the way we understand the science and treat the disease manifestations. GLP-1s may not cure Alzheimer’s as a monotherapy, but they are reshaping how we think about the interface of neurodegenerative disease etiology, metabolic health, vascular function and they likely will cement themselves as foundational tools in delaying cognitive decline across aging populations.

- Selman A, Burns S, Reddy AP, Culberson J, Reddy PH. The Role of Obesity and Diabetes in Dementia. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Aug 17;23(16):9267. doi: 10.3390/ijms23169267. PMID: 36012526; PMCID: PMC9408882.

- Chuansangeam M, Phadungsaksawasdi P, Park HJ, Yang Y-H. Exploring the link between GLP-1 receptor agonists and dementia: A comprehensive review. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease Reports. 2025;9.

- Comparative effectiveness of glucagon-like peptide-1 agonists, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors, and sulfonylureas on the risk of dementia in older individuals with type 2 diabetes in Sweden: an emulated trial study Tang, Bowen et al. eClinicalMedicine, Volume 73, 102689

- A Cellular Perspective on Brain Energy Metabolism and Functional Imaging Magistretti, Pierre J. et al. Neuron, Volume 86, Issue 4, 883 - 901

- Yassine HN, Self W, Kerman BE, et al. Nutritional metabolism and cerebral bioenergetics in Alzheimer's disease and related dementias. Alzheimer's Dement. 2023; 19: 1041–1066. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12845

- Cunnane SC, Trushina E, Morland C, Prigione A, Casadesus G, Andrews ZB, Beal MF, Bergersen LH, Brinton RD, de la Monte S, Eckert A, Harvey J, Jeggo R, Jhamandas JH, Kann O, la Cour CM, Martin WF, Mithieux G, Moreira PI, Murphy MP, Nave KA, Nuriel T, Oliet SHR, Saudou F, Mattson MP, Swerdlow RH, Millan MJ. Brain energy rescue: an emerging therapeutic concept for neurodegenerative disorders of ageing. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020 Sep;19(9):609-633. doi: 10.1038/s41573-020-0072-x. Epub 2020 Jul 24. PMID: 32709961; PMCID: PMC7948516.

- Cerasuolo, M.; Papa, M.; Colangelo, A.M.; Rizzo, M.R. Alzheimer’s Disease from the Amyloidogenic Theory to the Puzzling Crossroads between Vascular, Metabolic and Energetic Maladaptive Plasticity. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 861. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11030861

- Mekala A, Qiu H. Interplay Between Vascular Dysfunction and Neurodegenerative Pathology: New Insights into Molecular Mechanisms and Management. Biomolecules. 2025 May 13;15(5):712. doi: 10.3390/biom15050712. PMID: 40427605; PMCID: PMC12109301.

- Tang H, Donahoo WT, DeKosky ST, Lee YA, Kotecha P, Svensson M, Bian J, Guo J. Heterogeneous treatment effects of GLP-1RAs and SGLT2is on risk of Alzheimer's disease and related dementia in patients with type 2 diabetes: Insights from a real-world target trial emulation. Alzheimers Dement. 2025 Jun;21(6):e70313. doi: 10.1002/alz.70313. PMID: 40448382; PMCID: PMC12125485.

- Mélanie Fortier, Christian-Alexandre Castellano, Etienne Croteau, Francis Langlois, Christian Bocti, Valérie St-Pierre, Camille Vandenberghe, Michaël Bernier, Maggie Roy, Maxime Descoteaux, Kevin Whittingstall, Martin Lepage, Éric E. Turcotte, Tamas Fulop, Stephen C. Cunnane, A ketogenic drink improves brain energy and some measures of cognition in mild cognitive impairment, Alzheimer's & Dementia, Volume 15, Issue 5, 2019, Pages 625-634, ISSN 1552-5260,

- Cunnane SC, Courchesne-Loyer A, Vandenberghe C, St-Pierre V, Fortier M, Hennebelle M, Croteau E, Bocti C, Fulop T, Castellano CA. Can Ketones Help Rescue Brain Fuel Supply in Later Life? Implications for Cognitive Health during Aging and the Treatment of Alzheimer's Disease. Front Mol Neurosci. 2016 Jul 8;9:53. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2016.00053. PMID: 27458340; PMCID: PMC4937039.

- Chuansangeam M, Phadungsaksawasdi P, Park HJ, Yang YH. Exploring the link between GLP-1 receptor agonists and dementia: A comprehensive review. J Alzheimers Dis Rep. 2025 May 12;9:25424823251342182. doi: 10.1177/25424823251342182. PMID: 40370762; PMCID: PMC12075970.

- Michaelsen MK, Drasbek KR, Valentin JB, Svart M, Larsen JB, Kruuse C, Simonsen CZ, Blauenfeldt RA. GLP-1 receptor agonists as treatment of nondiabetic ischemic stroke—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2025. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.125.053075

- Moaket, O.S.; Obaid, S.E.; Obaid, F.E.; Shakeeb, Y.A.; Elsharief, S.M.; Tania, A.; Darwish, R.; Butler, A.E.; Moin, A.S.M. GLP-1 and the Degenerating Brain: Exploring Mechanistic Insights and Therapeutic Potential. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10743. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110743

- Liang Y, Doré V, Rowe CC, Krishnadas N. Clinical Evidence for GLP-1 Receptor Agonists in Alzheimer's Disease: A Systematic Review. J Alzheimers Dis Rep. 2024 May 7;8(1):777-789. doi: 10.3233/ADR-230181. PMID: 38746639; PMCID: PMC11091751.

- Gejl M, Gjedde A, Egefjord L, Møller A, Hansen SB, Vang K, Rodell A, Brændgaard H, Gottrup H, Schacht A, Møller N, Brock B, Rungby J. In Alzheimer's Disease, 6-Month Treatment with GLP-1 Analog Prevents Decline of Brain Glucose Metabolism: Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind Clinical Trial. Front Aging Neurosci. 2016 May 24;8:108. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2016.00108. PMID: 27252647; PMCID: PMC4877513.

- de la Torre JC. Vascular risk factors: a ticking time bomb to Alzheimer's disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2013 Sep;28(6):551-9. doi: 10.1177/1533317513494457. Epub 2013 Jun 28. PMID: 23813612; PMCID: PMC10852736.

- Nizari, S., Basalay, M., Chapman, P. et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor activation dilates cerebral arterioles, increases cerebral blood flow, and mediates remote (pre)conditioning neuroprotection against ischaemic stroke. Basic Res Cardiol 116, 32 (2021).

- Nørgaard CH, Friedrich S, Hansen CT, et al. Treatment with glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and incidence of dementia: Data from pooled double-blind randomized controlled trials and nationwide disease and prescription registers. Alzheimer's Dement. 2022; 8:e12268.

- AbuAlrob MA, Itbaisha A, Abujwaid YK, Abulehia A, Hussein A, Mesraoua B. Exploring the neuroprotective role of GLP-1 agonists against Alzheimer's disease: Real-world evidence from a propensity-matched cohort. J Alzheimers Dis Rep. 2025 Oct 16;9:25424823251388650. doi: 10.1177/25424823251388650. PMID: 41122341; PMCID: PMC12536097.

- Kopp KO, Glotfelty EJ, Li Y, Greig NH. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists and neuroinflammation: Implications for neurodegenerative disease treatment. Pharmacol Res. 2022 Dec;186:106550. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2022.106550. Epub 2022 Nov 11. PMID: 36372278; PMCID: PMC9712272.

- Fessel J. All GLP-1 Agonists Should, Theoretically, Cure Alzheimer's Dementia but Dulaglutide Might Be More Effective Than the Others. J Clin Med. 2024 Jun 26;13(13):3729. doi: 10.3390/jcm13133729. PMID: 38999294; PMCID: PMC11242057.

- Cummings JL, Atri A, Feldman HH, Hansson O, Sano M, Knop FK, Johannsen P, León T, Scheltens P. evoke and evoke+: design of two large-scale, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 studies evaluating efficacy, safety, and tolerability of semaglutide in early-stage symptomatic Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2025 Jan 8;17(1):14. doi: 10.1186/s13195-024-01666-7. PMID: 39780249; PMCID: PMC11708093.

- https://www.novonordisk.com/content/nncorp/global/en/news-and-media/news-and-ir-materials/news-details.html?id=916462

- Liu, PP., Xie, Y., Meng, XY. et al. History and progress of hypotheses and clinical trials for Alzheimer’s disease. Sig Transduct Target Ther 4, 29 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-019-0063-8

- Lin, Ai-Ling*; Aware, Chetan. Rapamycin as a preventive intervention for Alzheimer’s disease in APOE4 carriers: Targeting brain metabolic and vascular restoration. Neural Regeneration Research 21(2):p 685-686, February 2026. | DOI: 10.4103/NRR.NRR-D-24-01006

- Kostrzewska P, Kuca P, Witek P, Małyszko J, Madetko Alster N, Alster P. SGLT-2 Inhibitors in the Prevention and Progression of Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Narrative Review. Neurol Ther. 2025 Dec;14(6):2295-2312. doi: 10.1007/s40120-025-00832-9. Epub 2025 Oct 10. PMID: 41071460; PMCID: PMC12623600.

- Gonzalez-Lima F, et al. Mitochondrial respiration as a target for neuroprotection and cognitive enhancement. Biochem Pharmacol (2013), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2013.11.010

- Aron, L., Ngian, Z.K., Qiu, C. et al. Lithium deficiency and the onset of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 645, 712–721 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09335-x

- Govindugari, V.L.; Golla, S.; Reddy, S.D.M.; Chunduri, A.; Nunna, L.S.V.; Madasu, J.; Shamshabad, V.; Bandela, M.; Suryadevara, V. Thwarting Alzheimer’s Disease through Healthy Lifestyle Habits: Hope for the Future. Neurol. Int. 2023, 15, 162-187. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint15010013

- Targeting Sleep Physiology to Modulate Glymphatic Brain Clearance Timo van Hattem, Lieuwe Verkaar, Elena Krugliakova, Nico Adelhöfer, Marcel Zeising, Wilhelmus H. I. M. Drinkenburg, Jurgen A. H. R. Claassen, Róbert Bódizs, Martin Dresler, and Yevgenia Rosenblum Physiology 2025 40:3, 271-290

- Nutrition state of science and dementia prevention: recommendations of the Nutrition for Dementia Prevention Working Group Yassine, Hussein N et al. The Lancet Healthy Longevity, Volume 3, Issue 7, e501 - e512

Related studies