Emergence of Specialized Mitochondrial Networks: A ‘Divide and Conquer’ Strategy for Metabolic Demands

Mitochondrial Origin and Structure. Mitochondria evolved from ancient bacterial symbionts, preserving unique genetic material and a double membrane. This evolutionary heritage explains their exceptional roles in eukaryotic cells, where they must constantly adjust to varying metabolic demands.

Balancing Energy and Biosynthesis. Rather than serving as mere “power plants,” mitochondria orchestrate both ATP production and biosynthetic processes. Enzymes like P5CS allow them to pivot between fueling immediate energy needs and synthesizing essential building blocks for cell growth, repair, and proliferation.

Specialized Subpopulations. Within a single cell, mitochondria can form distinct subpopulations, each optimized for different tasks. Some focus on oxidative phosphorylation, while others drive biosynthesis—creating an internal “division of labor” that boosts overall cellular efficiency.

Health Impacts. When mitochondrial balance falters, a range of conditions—metabolic disorders, cancers, neurodegeneration, and poor wound healing—can develop. Inadequate ATP production, stalled biosynthesis, and toxic intermediates all contribute to disease progression.

Introduction

In our ongoing series on mitochondrial health, we’ve often emphasized how critical these organelles are for sustaining a robust healthspan—and how their dysfunction can drive age-related diseases. Known popularly as the “powerhouses of the cell,” these tiny organelles sit at the heart of our metabolic machinery, converting nutrients into energy that keeps tissues and organs running smoothly. But as we look across a range of age-related conditions—from neurodegenerative disorders to cardiovascular disease—we see a common thread: when mitochondria falter in their ability to power our cells, the seeds of cellular and tissue dysfunction are sown.

However, focusing solely on their role as “power plants” overlooks mitochondria’s extensive metabolic, biosynthetic, and signaling capacities. Most mammalian cells house anywhere from 50 to over 1,000 of these organelles, and they don’t just work in isolation. Instead, they form an intricate network—constantly fusing, dividing, and communicating with one another—much like an orchestrated ensemble.

Mitochondria carry out two particularly important jobs that help cells survive and grow. The first and most widely understood is energy production through a process called oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). Within the folds of the mitochondrion’s inner membrane—known as cristae—energy-rich molecules like glucose and fatty acids are broken down into high-energy intermediates (NADH and FADH₂). These intermediates feed electrons to the electron transport chain (ETC), a sequence of four protein complexes (I–IV) embedded in the cristae. Picture a factory conveyor belt: electrons move from one complex to the next, releasing energy along the way to pump protons (H⁺) across the membrane. Finally, that proton gradient drives ATP synthase—an enzyme that “prints” molecules of ATP, the universal energy currency for cells.

Just as a modern factory doesn’t only produce power, mitochondria also serve as cellular construction sites. In resource-rich environments—well-supplied tissues or lab cultures overflowing with nutrients—these organelles channel a portion of their “fuel” into biosynthetic pathways. You can imagine these pathways as specialized assembly lines, where carbon and other key elements are pieced together to form amino acids, lipids, nucleotides, and more. Proline and ornithine, for instance, are two amino acids partly manufactured in mitochondria. They play a vital role in protein synthesis, wound healing, polyamine production (the creation of small, nitrogen-rich molecules critical for cell growth), and collagen formation.

Given these dual roles—energy production and biosynthesis—one question looms large: how do mitochondria decide which job to prioritize when resources are limited? A new study in Nature titled “Cellular ATP demand creates metabolically distinct subpopulations of mitochondria” has begun to shed light on this puzzle. The researchers found that within a single cell, mitochondria can organize themselves into specialized subsets, some prioritizing ATP production while others focus on making the building blocks needed for cellular growth. This discovery hints that “decision-making” within our cells may be more nuanced than previously imagined, and that mitochondria themselves may respond dynamically to local demands.

In the sections that follow, we’ll examine the evolutionary roots of this adaptability, the mechanisms enabling “divide and conquer” resource allocation, and how these principles manifest in both health and disease.

Evolutionary Perspective: A Deeply Rooted Adaptability

Having explored how mitochondria might juggle two essential roles—fuel generation and biosynthesis—one might wonder how these organelles acquired such a multifaceted skill set in the first place. The answer lies in their ancient origins and the evolutionary forces that transformed them from free-living bacteria into key contributors to complex life on Earth.

The Endosymbiotic Origin

The leading hypothesis—often called the endosymbiotic theory—proposes that an ancestral host cell engulfed a proteobacterium capable of aerobic respiration. In exchange for shelter and nutrients, the bacterium provided ATP to its host, gradually surrendering many of its genes to the host’s nucleus. Despite billions of years of evolution, modern mitochondria still bear the hallmarks of this primordial partnership—such as a small circular genome and a double membrane.

Why Multiple Subpopulations?

Early eukaryotic cells likely gained a survival edge by toggling between catabolism and anabolism to match changing environmental demands. Specialized mitochondrial subpopulations may have emerged as a natural extension of this strategy, enabling cells to pivot quickly from high-energy activities (like movement or stress responses) to biosynthetic endeavors (like reproduction or growth). Over time, these adaptive pathways became embedded in mitochondrial biology, ensuring that mitochondria could respond flexibly when resources or conditions shifted.

Not all eukaryotes use mitochondria for the same exact processes. For example, parasites like Trypanosoma (the culprit behind sleeping sickness) house specialized mitochondrial forms known as kinetoplasts, demonstrating how evolutionary pressures can radically reshape mitochondrial functions. Studying these wide-ranging adaptations can illuminate the fundamental plasticity of mitochondrial networks and help explain how subpopulations might evolve in more complex species.

As life moved from single-celled to multicellular forms, the need for carefully orchestrated energy production and biosynthesis soared. Features like mitochondrial fusion, fission, and the emergence of discrete subpopulations likely played key roles in supporting larger, more specialized tissues. Those same cellular “divide and conquer” tactics may have underpinned the rise of complex multicellular life. By keeping different metabolic responsibilities in separate mitochondrial pools, cells could tailor their internal resources to specific developmental stages or environmental stresses.

Altogether, these evolutionary insights remind us that mitochondria’s dual roles in energy production and biosynthesis are deeply rooted in the past. Their capacity for flexible resource allocation—refined across billions of years—still underlies much of their adaptability today.

Divide and Conquer: A New Perspective on Mitochondrial Resource Allocation

Building on our understanding of how mitochondria evolved to handle multiple metabolic responsibilities, let’s turn to the question of how these organelles manage competing demands in real time—particularly under challenging conditions. While it might seem intuitive that mitochondria would devote all their resources to ATP production when nutrients run scarce, research reveals a more nuanced “divide and conquer” strategy.

Indeed, our bodies are constantly shifting between nutrient surplus and shortage, and cells must allocate limited resources carefully. One might assume that under nutrient-poor conditions, mitochondria would focus exclusively on churning out ATP—curtailing other operations like proline synthesis. Surprisingly, recent findings suggest otherwise: rather than shutting down biosynthesis, mitochondria distribute tasks among distinct subpopulations. Much like a city with specialized districts, certain mitochondria handle high-efficiency energy production while others dedicate themselves to anabolic (building) processes. This division of labor keeps cells supplied with both the energy and the construction materials necessary for survival and growth.

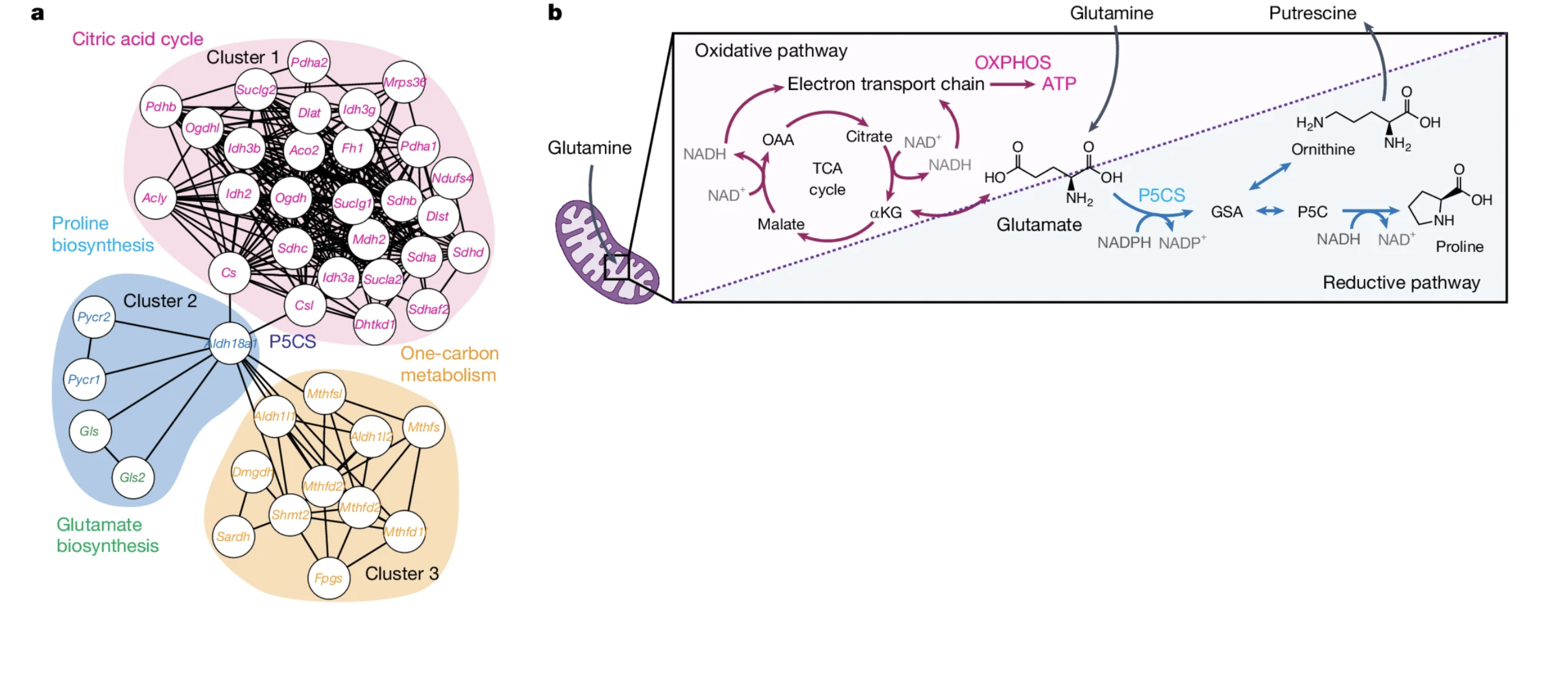

At the heart of this metabolic multitasking lies an enzyme called pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthase (P5CS)—a central switchboard connecting the TCA (Krebs) cycle, amino acid biosynthesis, and one-carbon metabolism. By routing molecules across these pathways, P5CS effectively tunes the cell’s metabolic outputs, shifting the balance between robust ATP generation and the production of essential biomolecules.

Why Is P5CS So Pivotal?

- Proline and Ornithine Production: P5CS channels TCA cycle intermediates (i.e. glutamate from α-ketoglutarate) into proline and ornithine biosynthesis (Berg et al., Biochemistry, 8th ed.). Proline not only serves as a protein building block but also influences cell signaling, redox balance, and stress resilience. Ornithine feeds into the urea cycle and supports polyamine synthesis—molecules crucial for cell proliferation.

- Adaptive Resource Management: With P5CS acting as metabolic “traffic control,” cells avoid using up all potential building materials for ATP alone. Instead, they can seamlessly pivot among producing more ATP, synthesizing extra amino acids, or stockpiling one-carbon units for nucleotide formation.

- Dynamic Modulation: In nutrient-rich environments, P5CS ramps up anabolic machinery, stockpiling critical building blocks for growth and repair. Under tougher conditions, its activity can be dialed back, maintaining baseline ATP levels without fully shutting off biosynthesis.

Together, these features highlight just how deeply interwoven energy production and biosynthetic demands are within mitochondria. By modulating P5CS—and thus the flow of metabolic intermediates—cells fine-tune the balance between fueling immediate energy needs and constructing vital macromolecules. Ultimately, mitochondria are not passive power stations, but decision-making hubs with the ability to adapt rapidly to environmental cues.

Key Takeaways (Divide and Conquer)

- Mitochondria employ a “divide and conquer” strategy, assigning different subpopulations to either ATP production or biosynthesis.

- P5CS serves as a key regulatory enzyme, routing metabolic intermediates between energy needs and anabolic pathways.

- This flexibility ensures cells can meet both immediate energy demands and long-term growth requirements.

Balancing Energy Production and Biosynthesis Under Nutrient Stress

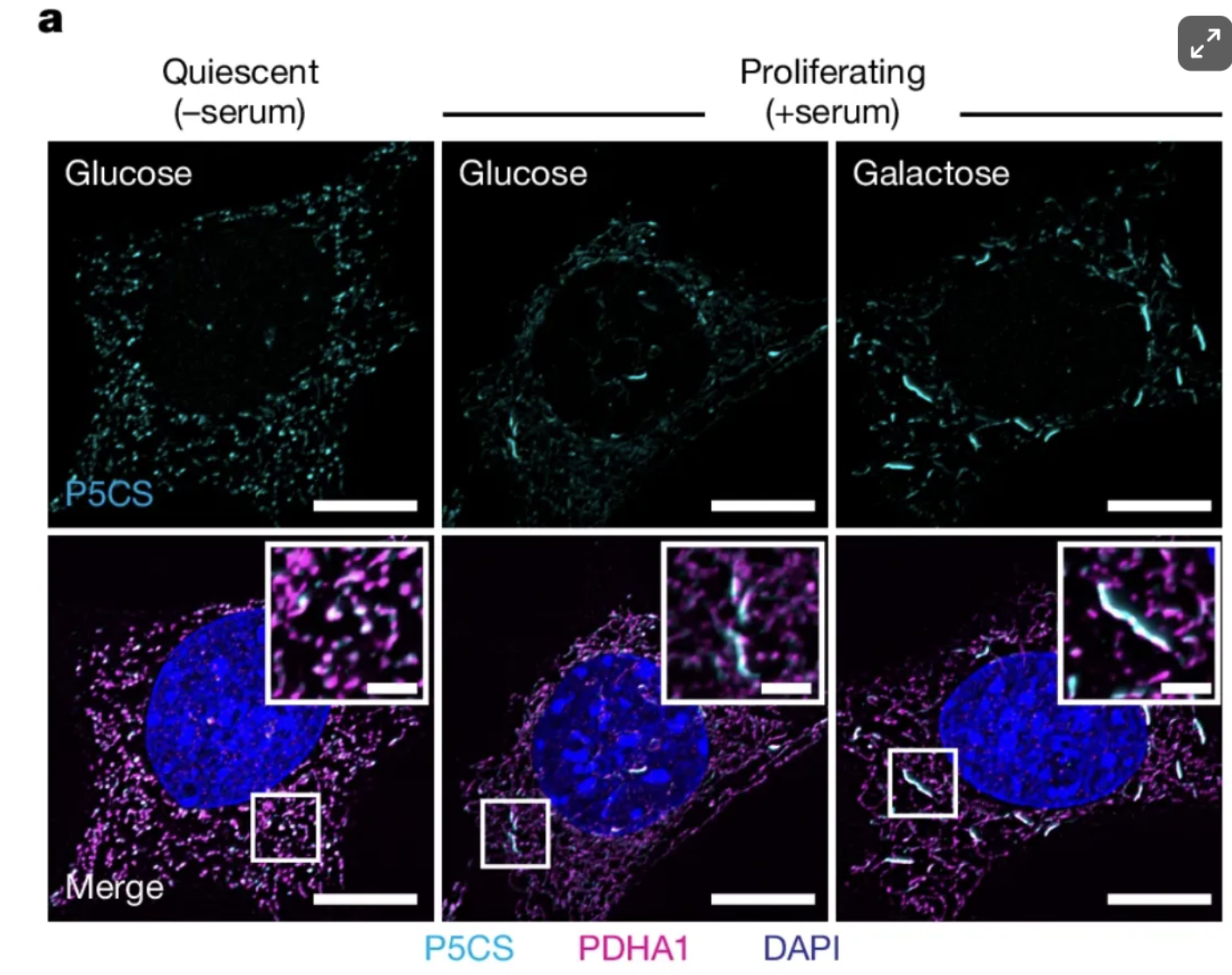

One of the study’s most surprising findings arose under conditions of glucose deprivation—a scenario that pushes cells to rely on oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) for ATP. In theory, you’d expect cells to funnel every available nutrient into ATP generation, sacrificing amino acid biosynthesis in the process. Instead, the researchers observed that even under glucose-starved conditions, cells managed to maintain their intracellular levels of proline. It’s a striking example of how cells can juggle high-priority needs—like energy production—without abandoning other essential tasks.

How do cells pull off this metabolic balancing act? The study points back to P5CS as a key player. Under stressors that ramp up OXPHOS—such as glucose deprivation—P5CS reconfigures itself into filamentous clusters within a select subset of mitochondria. This localization is significant because it physically concentrates the biosynthetic machinery where it can operate in tandem with heightened energy production. By forming filaments in only certain mitochondria, P5CS can maintain proline (and ornithine) synthesis without monopolizing the entire mitochondrial network—allowing other mitochondria to keep prioritizing ATP generation. The result is a division of labor that ensures the cell’s limited carbon sources are simultaneously funneled into both immediate energy needs and the creation of vital building blocks.

What makes these P5CS filaments especially intriguing is that the process can be reversed on the fly. When proline or ornithine is added externally—essentially removing the cell’s urgent need to manufacture these amino acids—P5CS filaments break down. In other words, the cell “knows” when it can shift resources elsewhere, and it neatly disassembles the P5CS clusters once their job is done. This built-in feedback loop keeps mitochondria tuned to the cell’s immediate needs, whether that’s fueling OXPHOS or stocking up on vital amino acids.

Such reversible enzyme clusters highlight an important concept: when metabolic pathways are physically organized into clusters—often called “metabolons”—they work more efficiently because the necessary reactions happen side by side. In other words, if enzymes like P5CS gather near the main sites of energy production in mitochondria, the cell can quickly reroute carbon to either ATP generation or biosynthesis, depending on what it needs at the time. This rapid-response arrangement keeps vital metabolic processes running smoothly and prevents bottlenecks when resources are tight.

In essence, P5CS filament formation serves as a litmus test for how cells fine-tune metabolic priorities. Even in lean times, they find ways to support both the “power plant” functions of mitochondria and their “assembly lines” for critical molecules. This dynamic framework illustrates just how adept our cells are at making the most of limited resources—an evolutionary survival skill refined across eons.

Key Takeaways

- Under nutrient deprivation, certain mitochondria form P5CS filaments, preserving amino acid biosynthesis alongside ATP production.

- The reversibility of filament formation offers a rapid-response mechanism, fine-tuning metabolic output according to changing demands.

- Spatial clustering of enzymes (metabolons) enhances efficiency and prevents resource bottlenecks.

Emergence of Functionally Distinct Mitochondria

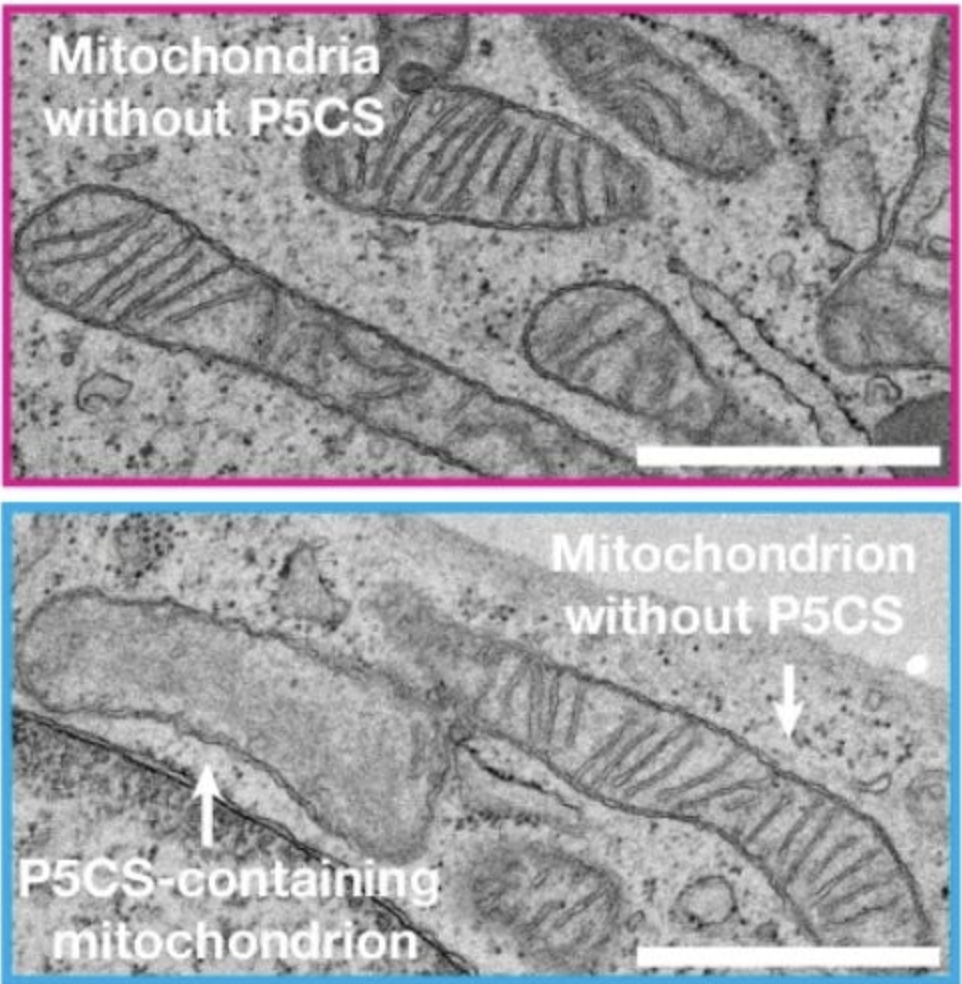

Shifting our focus from enzyme organization to the organelles themselves, another key insight from the study was the identification of functionally distinct mitochondrial subpopulations. Researchers noticed that mitochondria hosting P5CS filaments lacked ATP synthase, the enzyme crucial for generating ATP. This finding challenges the long-standing assumption that all mitochondria in a cell operate uniformly as “powerhouses.” Instead, it suggests that some mitochondria specialize in biosynthesis, while others continue to produce ATP.

The study revealed that filament-rich mitochondria also had few or no cristae—the folded structures in the inner membrane where the electron transport chain typically resides. In their place were layered protein formations most likely composed of assembled P5CS, signifying a structural pivot toward anabolic processes rather than oxidative phosphorylation.

This architectural shift highlights mitochondria’s adaptability. Different groups of mitochondria within the same cell can reorganize both their membranes and metabolic focus. By downplaying ATP synthase and altering their internal structure, these specialized mitochondria devote more resources to proline and ornithine biosynthesis, while neighboring mitochondria maintain fully developed cristae for robust ATP generation.

Ultimately, these observations paint a portrait of a finely tuned system in which subpopulations of mitochondria function as “factory lines” for building materials, while others act as “power plants.” Such a division of labor not only enriches our understanding of metabolic balance under shifting or stressful conditions but also illustrates why mitochondria remain a central focus in biomedical research.

Key Takeaways (Distinct Mitochondria)

- Certain mitochondria lack ATP synthase and focus on anabolic tasks, while others maintain ATP generation.

- Structural differences (i.e. fewer cristae) reflect a pivot toward biosynthesis.

- This division of labor underscores the specialized roles mitochondria can assume within a single cell.

Clinical and Disease Implications

Why does it matter that mitochondria can skillfully juggle energy production and biosynthesis? Because disruptions in these balancing acts have been linked to a range of diseases—from metabolic syndromes like type 2 diabetes to cancer and beyond.

Metabolic Diseases: Diabetes and Obesity

Mitochondria lie at the core of nutrient handling and energy balance, making them pivotal in the development of obesity and type 2 diabetes. In these conditions, chronic mismatches between calorie intake and energy expenditure often go hand-in-hand with mitochondrial dysfunction. For example, an overload of fatty acids can swamp the mitochondria’s oxidative pathways, generating harmful intermediates (i.e. acylcarnitines) that interfere with insulin signaling. Meanwhile, incomplete oxidation of glucose or fats elevates reactive oxygen species (ROS), further impairing the mitochondrial network.

Under normal conditions, mitochondria deftly switch between ATP production and biosynthetic tasks—activating, for instance, the P5CS pathway to produce proline as needed. But in type 2 diabetes or obesity, this “divide and conquer” approach can falter. Instead of smoothly reallocating resources, dysfunctional mitochondria may accumulate unprocessed metabolites or fail to produce enough ATP. These shortfalls often manifest as insulin resistance—where cells can’t properly respond to insulin’s glucose-lowering signal—and broader metabolic stress such as elevated blood sugar and abnormal lipid levels.

By targeting pathways that govern this metabolic balancing act—like adjusting P5CS activity or improving mitochondrial dynamics—researchers hope to restore the cell’s ability to handle both ATP demands and biosynthetic needs. Early studies suggest that recalibrating these mitochondrial functions may help normalize glucose and lipid metabolism, hinting at new therapeutic strategies for managing or even preventing metabolic diseases.

Cancer: The Warburg Effect and Proline Metabolism

Early in the 20th century, biochemist Otto Warburg observed that many cancer cells favor glycolysis—a relatively inefficient way to generate ATP—over oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), even when oxygen is abundant. This phenomenon, now called the Warburg effect, helps fuel rapid cell growth by funneling carbon-based nutrients (like glucose) into building blocks for nucleotides, amino acids, and lipids. In other words, cancer cells often sacrifice ATP efficiency to ramp up the production of molecules they need for prolific division.

At the same time, emerging evidence shows that OXPHOS remains integral in numerous tumors. Far from being abandoned, mitochondria still help bolster ATP levels and produce key metabolic intermediates—such as aspartate and other TCA cycle products—that support aggressive proliferation. Rather than a strict “either/or” scenario, many cancer cells skillfully toggle between glycolysis and OXPHOS, depending on immediate demands.

Alongside these shifts in energy generation, certain cancers lean heavily on amino acid biosynthesis, including the metabolism of proline. Although often dismissed as just another building block for proteins, proline offers much more. It can help stabilize redox balance by shuttling electrons within the cell, modulate levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and influence signaling pathways that drive tumor growth.

Crucially, some cancer cells appear to “uncouple” their mitochondria: certain subpopulations are optimized for ATP production, while others focus on proline synthesis and related biosynthetic tasks. This division of labor enables tumors to fulfill both energy needs and the construction of biomolecules needed for rapid cell proliferation—giving them a competitive edge over normal cells.

In light of this metabolic flexibility, targeting proline metabolism—for instance, by inhibiting the enzyme P5CS—has emerged as a promising therapeutic approach. By disrupting a tumor’s supply of proline, researchers may effectively cut off a key resource that fuels rapid proliferation. Crucially, inhibiting this pathway might spare healthy tissues that can rely on alternative metabolic routes or lower proline requirements. This selectivity is a key consideration in oncology, where conventional treatments can inadvertently damage normal cells alongside cancer cells. By homing in on P5CS-driven proline biosynthesis, researchers aim to capitalize on the unique metabolic vulnerabilities of tumor cells, paving the way for more precise and potentially less toxic anticancer interventions.

Neurodegenerative Conditions: Impaired Mitochondrial Dynamics

Neurons—the brain’s key communicators—have exceptionally high energy demands. Although they comprise only a small fraction of the body’s mass, they consume a disproportionately large share of its oxygen and glucose. This constant requirement for ATP powers synaptic transmission, maintains ion gradients, and supports the elaborate architecture of neuronal networks. At the same time, neurons need a continuous supply of amino acids and other essential precursors to repair and remodel synapses and axons. When the normal fusion-fission cycles of mitochondria—or the activities of crucial enzymes like P5CS—are disrupted, neurons struggle to meet these dual demands.

This dysfunction is especially evident in Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Huntington’s diseases, where damaged mitochondria and oxidative stress converge to undermine neural health. Under such conditions, mitochondria may fail to generate sufficient ATP or synthesize enough building blocks, leaving neurons vulnerable to energy deficits and toxic protein aggregates. Over time, these stresses accelerate neuronal death, progressively eroding cognitive abilities and motor control.

By preserving or restoring healthy mitochondrial subpopulations—those adept at both ATP production and amino acid synthesis—researchers aim to bolster neuronal resilience. Promoting mitochondrial fusion, for instance, can create more interconnected networks capable of meeting localized ATP demands, while fine-tuning P5CS helps ensure a reliable flow of proline and related metabolites. Together, these targeted strategies hold promise for reinforcing neuronal function and potentially slowing—or even reversing—the degenerative cascades that characterize debilitating brain disorders.

Conclusion

From powering our cells with ATP to forging amino acids that form collagen and other biomolecules, mitochondria are far more than simple “powerhouses.” Their ability to dynamically juggle energy production and biosynthesis underpins myriad physiological processes—tissue repair, neuronal maintenance, and metabolic homeostasis among them. At the center of this versatility lie pivotal factors like P5CS and the fine-tuned equilibrium of fusion and fission, which direct how and when mitochondria channel resources into ATP or vital building blocks like proline and ornithine.

Such insights reveal not just the complexities of mitochondrial biology but also how subtle dysfunctions in these organelles can reverberate across multiple cellular pathways. Conditions ranging from type 2 diabetes to cancer and neurodegeneration often share a theme of derailed mitochondrial dynamics—further highlighting the importance of these organelles in both health and disease. By viewing mitochondria as adaptable “control rooms” rather than static “power plants,” we open new therapeutic avenues—strategies that could selectively target dysfunctional mitochondrial subsets or fine-tune the balance between energy generation and biosynthesis.

As our understanding of these “divide and conquer” tactics grows—whether through insights on P5CS filament assembly or the regulatory interplay between fusion and fission—we move closer to more targeted interventions. In doing so, we continue to unearth the astonishing adaptability of mitochondria: a legacy of billions of years of evolution, still shaping how life flourishes and survives even under the most challenging conditions.