Harnessing Chronobiology for Metabolic Health: The Role of Brown Fat and Circadian Rhythms

Prefer to listen? Hit play for a conversational, audio‑style summary of this article’s key points.

Circadian rhythms strongly influence metabolism, orchestrating daily fluctuations in hormones, enzymes, and nutrient handling. When disrupted—due to shift work, irregular meals, or nighttime light exposure—metabolic health deteriorates, increasing the risk of insulin resistance and obesity. For instance, chronic circadian misalignment can diminish rhythmic expression of key metabolic regulators like AMPK, SIRT1, and mTOR, contributing significantly to impaired energy balance.

Brown adipose tissue (BAT) actively contributes to metabolic health by burning calories through thermogenesis. Unlike white adipose tissue, BAT expresses high levels of uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1), enabling it to dissipate energy as heat. Recent studies confirm adults possess functional BAT that, although modest in quantity, can substantially enhance metabolism, particularly when activated by mild cold exposure, with documented metabolic improvements such as enhanced glucose tolerance and fat oxidation.

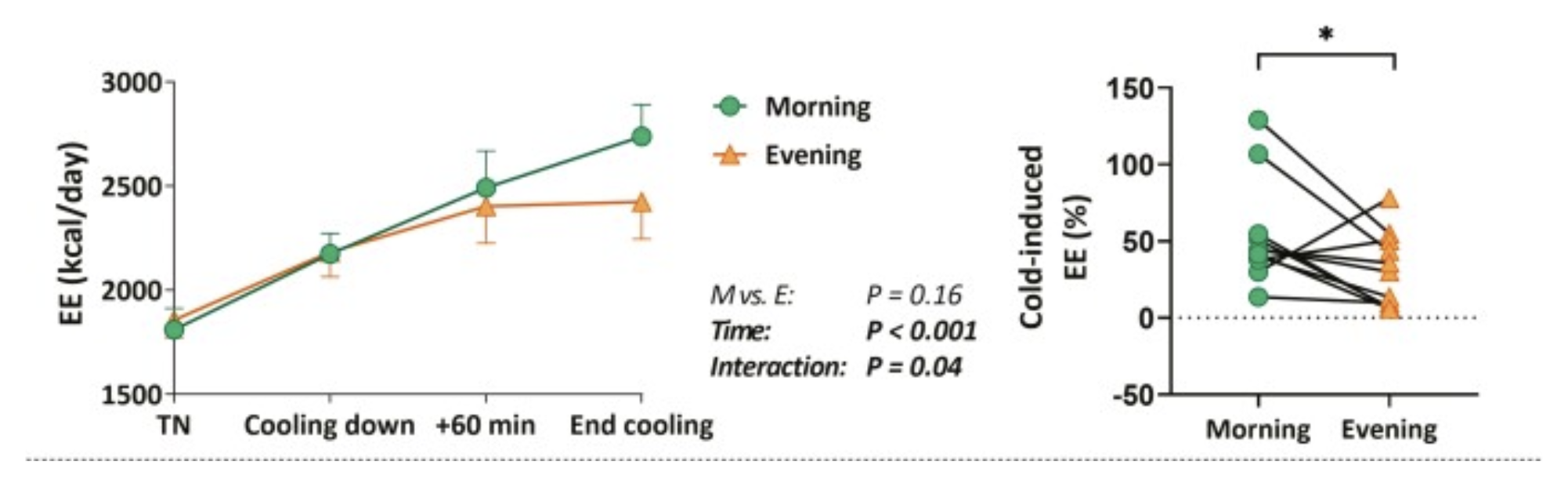

Recent studies indicate strong circadian variations in brown fat activity. Matsushita et al. (2021) observed that men exhibit significantly higher BAT thermogenesis and fat oxidation rates in the morning compared to the evening. Similarly, Straat et al. (2022) found that morning cold exposure increased men's energy expenditure significantly more (~30% higher) than evening exposure, highlighting the circadian sensitivity of thermogenic fat activation.

Gender differences in circadian BAT activation were also notable. While men showed approximately a 54% increase in cold-induced energy expenditure in the morning versus just 30% in the evening, women displayed a more consistent thermogenic response (30–37%) regardless of time. However, women experienced notably greater mobilization of free fatty acids in the morning (a 94% increase) compared to evening exposure (20% increase), indicating distinct sex-specific circadian metabolic responses.

Meal timing plays a critical role in optimizing BAT activity and energy expenditure. Time-restricted feeding (TRF), which confines caloric intake to an 8–10-hour window aligned with daylight, leverages circadian patterns when metabolic and BAT thermogenic responses naturally peak. Studies demonstrate that aligning meal schedules with the body's metabolic rhythm enhances energy utilization and may support metabolic improvements such as enhanced insulin sensitivity and better lipid handling.

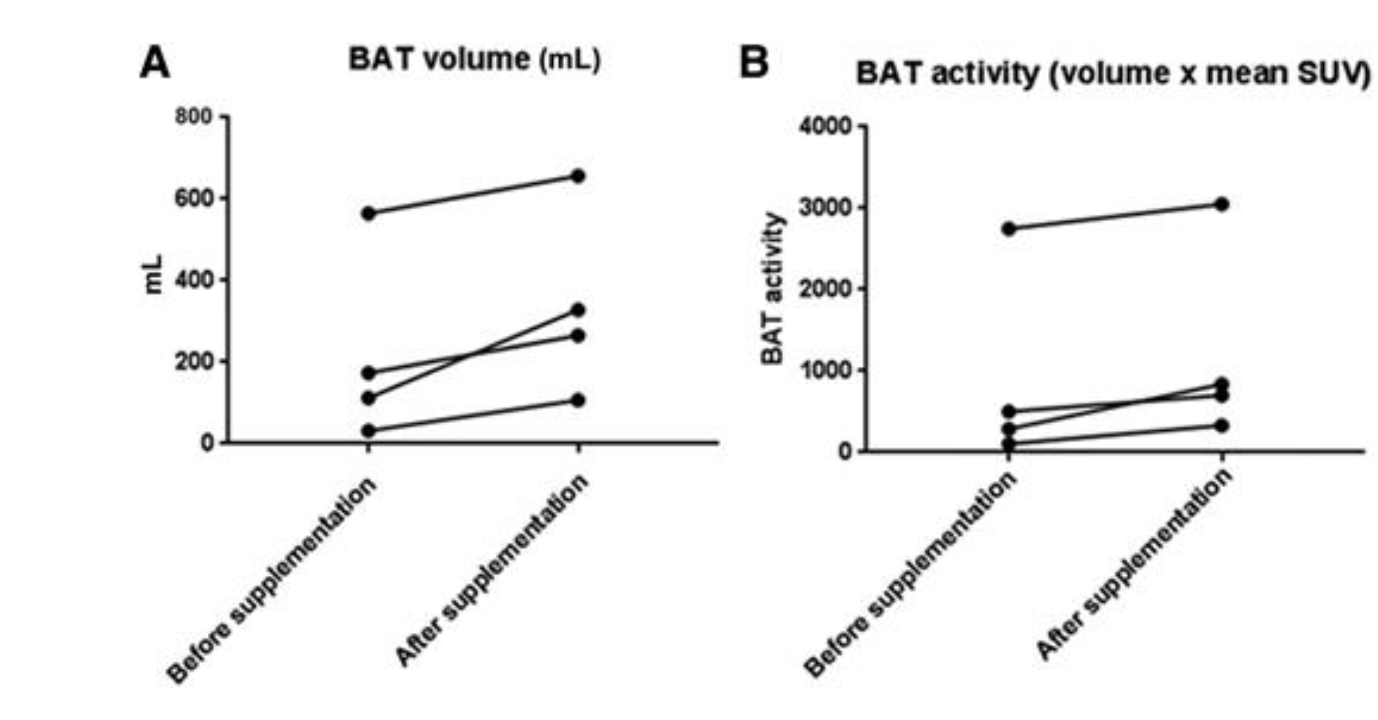

Melatonin, the hormone that signals nighttime to the body, significantly influences brown fat activation. Halpern et al. (2019) demonstrated that melatonin supplementation in individuals increased BAT volume and activity, improved insulin sensitivity, and reduced cholesterol and triglyceride levels. This underscores the importance of preserving natural melatonin rhythms through consistent light-dark cycles to maximize metabolic health.

Lifestyle practices, such as regular morning cold exposure, strategically timed meals, and proper management of light exposure, are promising ways to leverage circadian biology. Morning cold exposure can boost daily calorie burning by as much as ~150 kcal/day in individuals with active BAT, suggesting a practical window for enhancing metabolic outcomes through circadian-aligned behavior.

Introduction: Why Circadian Rhythms and Brown Fat Matter

Most of us recognize that our bodies follow daily patterns—we grow sleepy around the same time each night, experience surges of alertness or hunger at familiar hours, and generally operate on a predictable cycle. These rhythms, known scientifically as circadian rhythms, extend far beyond sleep and wakefulness. They also regulate key aspects of metabolism: how we process glucose, burn fats, and respond to hormones like insulin.

Against the backdrop of rapidly escalating rates of obesity and diabetes, researchers have begun digging deeper into the ways circadian misalignment—from shift work, irregular meal times, or chronic sleep deprivation—might undermine our metabolic health. At the same time, renewed interest has centered on an intriguing form of body fat that bucks the traditional “calorie storage” role. Brown adipose tissue (BAT), once considered necessary only for infants, exists in adults and can burn calories by generating heat, a process known as thermogenesis. When conditions are right—such as exposure to mild cold—BAT ramps up energy expenditure, often leading to improvements in glucose metabolism and overall metabolic function.

Recent findings show that these two worlds—our daily biological rhythms and the heat-generating power of brown fat—may be more interlinked than anyone suspected. In a 2021 study titled Diurnal variations of brown fat thermogenesis and fat oxidation in humans, for instance, BAT proved significantly more active in the morning for the male participants than in the evening, suggesting that timing can directly influence how many calories this specialized fat burns. Such evidence highlights an interesting possibility: by aligning our behavior—meal schedules, exercise routines, and even light exposure—with our innate circadian rhythms, we might harness brown fat’s thermogenic capabilities more effectively. [1]

In this review, we will explore in detail not only how diurnal fluctuations in brown fat activity can translate into tangible metabolic gains but also how broader circadian principles underpin these shifts in energy balance. We begin by dissecting the 2021 study, which demonstrated a striking morning-versus-evening difference in brown fat thermogenesis, particularly in men. From there, we’ll expand our scope to include two additional investigations that reveal how factors like cold exposure, meal timing, and melatonin release modulate brown fat function across the day. By looking at both the molecular underpinnings—such as the expression of clock genes and thermogenic proteins—and the real-world interventions these findings suggest, we aim to give readers a comprehensive view of why timing matters for metabolic health. Ultimately, we’ll consider practical steps—ranging from structured cold exposure in the early hours to shifting mealtimes to better coincide with the body’s natural peaks in fat oxidation—that could help individuals sync their lifestyles to their internal clocks.

What Are Circadian Rhythms?

Simply put, a circadian rhythm is your body’s internal 24-hour “timer.” Yet behind that simplicity lies a sophisticated genetic program. At its core, a set of “clock genes”—notably CLOCK and BMAL1—form a molecular feedback loop. Early in the morning, CLOCK and BMAL1 proteins pair up and bind to DNA, boosting the production of other clock-related genes, such as PER and CRY. As PER and CRY build up in the cell over several hours, they eventually suppress the activity of CLOCK and BMAL1, halting their own production. By nightfall, when PER and CRY degrade, the repression lifts, and CLOCK-BMAL1 can restart the cycle. This constant rise and fall of gene products effectively creates a built-in clock that repeats every 24 hours. [1]

Although the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in the brain’s hypothalamus acts as a “master conductor,” peripheral tissues—including the liver, muscle, pancreatic islets, and even fat—run local versions of these cycles. The SCN synchronizes them via signals such as melatonin release (rising at night), cortisol patterns (peaking in early morning), and fluctuations in body temperature. Meanwhile, external cues such as light exposure, meal timing, and ambient temperature help “set” the SCN clock daily. When all these clocks are in sync, the body can coordinate energy metabolism with the time of day—for instance, gearing up to handle a breakfast meal soon after sunrise and powering down for cellular repair at night. [1]

Why does this matter for metabolism? In healthy rhythms, enzymes and hormones that manage fat storage, glucose uptake, and energy burning appear at just the right time. For example, the energy-sensing enzyme AMPK might peak in activity during certain hours, promoting the breakdown of stored fats when you’re most active. Meanwhile, mTOR (another central metabolic regulator) becomes more active at other times, aiding tissue repair and growth. The NAD⁺-dependent protein SIRT1, known for its role in aging and metabolism, also interacts closely with the clock machinery, fine-tuning energy balance and stress resistance. If these oscillations proceed normally, your body can efficiently manage blood sugar, lipid levels, and energy expenditure without excess strain. [1]

How Circadian Disruptions Drive Metabolic Dysfunction

Modern lifestyles often push our internal clocks to operate under unnatural conditions. Late-night screen exposure, rotating shift work, and irregular eating patterns can all scramble the delicate gene networks designed to keep us in sync with natural light-dark cycles. When these networks—centered on regulators like CLOCK, BMAL1, PER, and CRY—are chronically misaligned, enzymes that govern nutrient metabolism and cellular repair, such as AMPK, SIRT1, and mTOR, lose their rhythmicity. As a result, cells may struggle to detect energy surpluses or deficits at the appropriate times, leading to an increased risk of insulin resistance and weight gain. Rather than efficiently channeling glucose and lipids into or out of storage when needed, a misaligned system can over- or under-respond, slowly undermining the body’s metabolic stability. [2]

A study led by Straat and colleagues (2022) reveals just how sensitive our daily biology can be. In that work, 24 young adults (12 men and 12 women) each underwent a mild cold exposure twice—once in the morning (around 7:45 AM) and again in the evening (about 7:45 PM). Participants wore water-cooled suits that gradually lowered their skin temperature, prompting the body to generate heat either by shivering or activating brown fat, a process known as non-shivering thermogenesis. Throughout this challenge, researchers measured energy expenditure via indirect calorimetry (tracking oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production), monitored core and skin temperatures, and drew blood to gauge markers like free fatty acids and triglycerides. [2]

In men, the cold-induced energy expenditure in the morning shot up by approximately 54%, whereas the evening exposure only produced a 30% rise. Women exhibited a more uniform response, around 30–37% regardless of time of day, yet they still showed intriguing circadian variations—particularly in the release of free fatty acids. For instance, women saw a surge of around 94% in free fatty acid levels under morning cold conditions compared to just 20% in the evening, hinting at a more robust mobilization of stored energy earlier in the day. Women also appeared to tolerate cold better in the morning, reaching a lower shivering threshold. While men’s morning-to-evening gap was more pronounced, these findings collectively highlight how circadian fluctuations can shape how many calories are burned and how the body decides to tap into fat stores. [2]

Figure 1 shows how cold-induced energy expenditure (EE) was impacted by time of day and gender. In males, the increase in EE during cold exposure differed between morning and evening. [2]

This underscores that our internal clocks act as metabolic choreographers, cueing the right processes at the right time. When people consistently push these rhythms off-balance—by eating large meals late at night, skimping on sleep, or exposing themselves to bright light at 2 a.m.—they may be working against their built-in efficiencies for energy regulation. Over time, these cumulative missteps can fuel metabolic disorders, including obesity and type 2 diabetes. Conversely, aligning daily activities with an optimal circadian window may pay dividends, whether it’s timing a brisk walk or a cool shower to harness higher thermogenic potential in the morning or ensuring nighttime behaviors reinforce, rather than disrupt, our natural biological nighttime. By seeing the day not just as a horizon for work and leisure but as an unfolding cycle of cellular processes, we can grasp why circadian rhythms are fundamental to metabolic health. [2]

What Is Thermogenic Fat? The Role of Brown and Beige Adipose Tissue

Adipose tissue often conjures images of unwanted body fat or energy storage gone awry, yet it is far more than a passive depot. In truth, there are multiple types of adipose tissue, each with unique molecular properties and physiological roles. White adipose tissue (WAT) is the most abundant form in adults, composed predominantly of large, lipid-filled cells that store excess calories and secrete various hormones—such as leptin and adiponectin—to help regulate appetite, metabolism, and inflammation. Although WAT is sometimes villainized in discussions of obesity, it does serve critical purposes, including cushioning organs, insulating the body, and delivering key signals that govern systemic energy balance. [2]

Brown adipose tissue (BAT), in contrast, has a completely different mission. Rather than hoarding energy, brown fat is specialized for burning it. Under the microscope, BAT appears darker because it is loaded with mitochondria—tiny organelles responsible for producing energy in cells—and contains a distinct protein called uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1). These features endow brown fat with the capacity for non-shivering thermogenesis. Rather than generating ATP, which is the usual energy currency for cellular work, BAT redirects the energy from nutrient oxidation into heat production. This capacity makes brown fat integral for thermoregulation, particularly in infants, who rely heavily on BAT to maintain body temperature before their ability to shiver matures. For decades, researchers believed BAT essentially vanished after infancy, but advances in imaging techniques revealed that many adults retain functional brown fat depots along the neck, spine, and shoulder blades. Although the quantity is typically small, its metabolic potential is significant—particularly if it can be coaxed into higher activity through environmental or pharmacological means. [2]

Adding further nuance to the story is the existence of beige adipose tissue (often abbreviated as bAT). Beige fat cells share features of both white and brown adipose tissue and can “flip” between states depending on external stimuli. When exposed to cold, certain hormones, or even specific food ingredients (such as capsaicin), white fat cells can take on a more “brown-like” profile and begin expressing UCP1, boosting their thermogenic activity. Conversely, if these signals subside, beige fat can revert closer to a white-fat phenotype, storing rather than burning energy. This malleability underscores an exciting possibility: if researchers can harness the browning process in humans, they may be able to expand the body’s energy-burning capacity and thereby combat obesity or metabolic syndrome more effectively. [2]

At the heart of brown and beige fat’s heat-generating ability is the protein UCP1, located in the inner mitochondrial membrane. Typically, mitochondria use an electrochemical gradient—built up by pumping protons (H⁺) across the inner membrane—to power ATP synthesis. However, in cells expressing UCP1, protons can flow back across the membrane without driving ATP production, releasing energy as heat. This “uncoupling” of fuel oxidation from ATP generation explains why brown fat is so metabolically active: instead of packaging energy into an immediately usable currency, it deliberately wastes it as warmth. In many ways, brown fat represents a physiological mechanism for dissipating excess caloric energy, a capacity that has drawn intense interest from researchers seeking new treatments for metabolic diseases. [2]

Activating BAT, or converting more white adipose tissue to the beige state, can be triggered by cold exposure, which stimulates the sympathetic nervous system to release norepinephrine. That norepinephrine, in turn, binds to receptors on brown or beige fat cells, setting off a cascade that enhances UCP1 production. Exercise may also help spur the browning process by producing certain irisin-like signals. At the same time, hormones such as melatonin can modulate BAT function by reinforcing circadian cues that govern when thermogenesis should peak. Although much remains to be learned about manipulating these pathways safely and effectively, the revelation that adults maintain a functional capacity for thermogenesis through brown and beige adipose tissue has prompted new possibilities. By understanding and harnessing these specialized cells, we may ultimately develop more refined strategies to bolster metabolic health—strategies that complement or even surpass traditional diet and exercise interventions. [2]

The Circadian Control of Thermogenic Fat

Our body’s ability to produce heat from stored energy is not merely “on” or “off.” Instead, brown adipose tissue (BAT) follows its own biological rhythms, much like the sleep-wake cycle that affects our other bodily functions. Genetic studies confirm that BAT contains clock genes similar to those in the brain and other tissues, cycling over 24-hour periods and influencing how effectively this specialized tissue can oxidize fats and release energy as heat. [1]

One of the most illuminating demonstrations of BAT’s daily fluctuations comes from a 2021 study by Matsushita and colleagues. In that investigation, 44 healthy young men were grouped according to their levels of brown fat, assessed via PET-CT scans. The researchers then used a metabolic chamber to monitor how these individuals burned calories after meals and during mild cold exposure at two distinct times of day: early morning (8–11 AM) versus evening (7–10 PM). The differences they observed were striking. Men with high amounts of BAT showed substantially greater diet-induced thermogenesis (the extra calories burned from processing a meal) and higher rates of fat oxidation when tested after breakfast. By contrast, in the evening test session, the energy-burning edge that high-BAT men held over their low-BAT counterparts largely disappeared. [1]

The pattern was even more pronounced under mild cold conditions. When exposed to temperatures ranging from 27°C down to 19°C, men in the high-BAT group experienced a boost in energy expenditure of about +150 kcal/day in the morning—a figure that dropped to roughly +50 kcal/day when the same participants underwent the cold challenge in the evening. Low-BAT individuals, meanwhile, showed only modest increases at both times of day. Notably, the high-BAT men also oxidized significantly more fat in the morning compared to the evening, supporting the notion that the body is biologically primed to burn more calories and mobilize more fat earlier in the day. [1]

From a practical standpoint, these findings help explain why certain lifestyle habits—like skipping breakfast—may interfere with weight management. If one of the prime windows for activating brown fat (through meal ingestion or minor cold exposure) is missed, the metabolic advantage that BAT can offer might be diminished for the rest of the day. More broadly, this work underscores the value of considering when we eat or cool our bodies, not just what we consume or how cold we get. Aligning daily routines with the natural upswing in BAT activity, especially in the morning, could prove to be a valuable strategy for enhancing energy expenditure and maintaining a healthier body weight. [1]

The Role of Light Exposure in BAT Activation

Light is one of the most potent cues for setting our internal clocks, influencing much more than just our sleep-wake cycle. In particular, exposure to bright or blue-tinged light in the evening can suppress the body’s production of melatonin, a hormone deeply involved in signaling nighttime to tissues throughout the body. Typically, melatonin levels rise after dark, peaking in the late evening to help regulate everything from sleep onset to metabolic processes in peripheral organs. When we flood our eyes with intense blue light at night—through late TV watching, smartphone use, or harsh indoor lighting—this circadian cue is blunted, and melatonin release is delayed or diminished. Recent research suggests that this reduction in melatonin could undercut brown adipose tissue (BAT) function, as melatonin has been implicated in driving certain thermogenic pathways. [3]

Conversely, catching early morning sunlight helps reset our master clock, located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), by providing a clear daytime signal. This morning synchronization not only stabilizes the daily rhythm of melatonin release (ensuring it remains confined to nighttime) but may also fortify the circadian cycles of peripheral tissues like brown fat. Studies of BAT activity have often reported enhanced thermogenesis early in the day—coinciding with a natural transition from elevated nighttime melatonin to the more active, wakeful phase of the circadian cycle. Although the exact mechanisms remain an active area of investigation, it is thought that well-synchronized melatonin rhythms could improve the sensitivity of BAT cells to cues such as norepinephrine, which is critical for non-shivering thermogenesis. [3]

From a practical standpoint, these insights underscore that maintaining a consistent light-dark schedule—optimally receiving bright, full-spectrum light in the morning and reducing blue-light exposure after sunset—can help preserve the normal melatonin surge at night. By extension, this nighttime melatonin rise may reinforce BAT’s cyclical readiness for thermogenesis, a process that peaks in the early hours and can be harnessed to manage energy balance and metabolic health more effectively. [3]

Meal Timing and BAT Activation

When we eat can be just as important as what we eat, especially when harnessing brown fat’s thermogenic potential. Research shows that the body’s metabolic machinery is tuned to process nutrients more efficiently earlier in the day, partly because of a natural spike in thermogenesis—including brown adipose tissue (BAT) activity—around morning and midday. By contrast, consuming large meals late in the evening or at night risks colliding with a period when BAT is relatively subdued and when overall insulin sensitivity may be lower. This mismatch can disrupt the body’s carefully orchestrated cycles of energy storage and expenditure, leading to greater fat accumulation and even pushing blood glucose levels higher than they might be at earlier hours. [3]

Time-restricted feeding (TRF)—one concentrates most daily caloric intake into a roughly 8–10-hour window aligned with daylight—builds on this principle. The idea is to optimize meal timing to coincide with the body’s natural surge in metabolic function. By limiting eating to a shorter span during the day, individuals effectively extend the overnight fast, during which insulin drops and tissues become more receptive to energy-burning cues. Evidence suggests that such an approach may not only bolster weight control and glucose tolerance but could also enhance brown fat function. When nutrients enter the bloodstream at a time when BAT is already more inclined to burn fuel, the overall thermogenic response can be amplified. Over days and weeks, this amplified response may cumulatively improve energy balance and curb excessive fat deposition. In short, meal timing that respects our circadian rhythms can help ensure that we are fueling the body when it is best equipped to handle, and even dissipate, incoming calories. [3]

How to Leverage Circadian Biology and Brown Fat Activation

One of the most intriguing insights from circadian research is how daily habits—when carefully timed—can amplify brown fat’s capacity to burn energy. Modern science has begun to tease out a few practical ways to make this happen. First, cold exposure stands out as a potent BAT stimulator. Whether through a brisk morning walk in cool air or a quick cold shower, exposing the body to lower temperatures can trigger non-shivering thermogenesis. In the work of Straat and colleagues (2022), the effect of such exposure was shown to vary significantly by time of day.

Men tested in the morning experienced a remarkable 54% rise in energy expenditure, while their evening sessions produced only a 30% jump. Women had a less stark contrast across morning and evening, but there was still evidence that thermogenesis and fatty acid mobilization were more pronounced early in the day. These findings suggest that morning cold exposure may yield the greatest metabolic payoff, making the first hours after waking an optimal window for anyone hoping to tap into BAT’s energy-burning benefits. [2]

Another avenue for leveraging circadian biology is to align meal timing with the body’s natural metabolic peaks. Time-restricted eating (TRE) or similar intermittent fasting approaches concentrate daily caloric intake into a shorter daytime window, reducing the chance of late-night meals that clash with a more dormant metabolic state. Early studies of TRE show improvements in weight control, insulin sensitivity, and markers of cardiovascular health, likely because these plans respect the body’s inherent rhythms. Additionally, the types of nutrients consumed can further support brown fat activation. Spicy compounds like capsaicin, catechins from green tea, and omega-3 fatty acids have all shown promise in promoting thermogenesis, especially when consumed during a period of heightened metabolic readiness. Thus, selecting the right foods—and eating them at biologically appropriate times—may work synergistically with BAT’s intrinsic schedule. [2]

Light exposure and melatonin regulation form the final piece of this circadian puzzle. Getting a healthy dose of bright light early in the day can help reset the master clock in the brain, reinforcing a robust rhythm that encourages energy-burning when we’re awake and rest when it’s dark. Equally important, limiting blue light after sunset helps ensure a solid rise in melatonin, the hormone that cues various tissues, including brown fat, to prepare for nighttime. In a 2019 investigation by Halpern and colleagues, researchers examined four patients with pineal gland damage who produced little to no melatonin. At baseline, these individuals had minimal brown fat detectable on PET–MRI scans. However, after three months of taking 3 mg of melatonin each night—mimicking a normal nocturnal surge—they showed a significant increase in BAT volume and activity and notable improvements in cholesterol levels, triglycerides, and insulin sensitivity. Although their body weights did not dramatically change in such a short timeframe, the bolstered BAT and improved metabolic markers speak to melatonin’s central role in thermogenesis. [3]

Figure 2 illustrates the changes in brown adipose tissue (BAT) volume (A) and BAT metabolic activity (B) in four patients before and after melatonin replacement therapy. The data show a statistically significant increase in both BAT volume and activity following three months of nightly melatonin supplementation. This suggests that melatonin directly modulates BAT function, potentially by enhancing thermogenic capacity through increased expression of UCP1 and heightened mitochondrial activity. [3]

Ultimately, this research emphasizes that circadian alignment—through early-day cold exposure, well-timed meals, and optimized light-dark cycles—can be a powerful driver of brown fat activation. For those looking to optimize metabolic health, these findings imply that it may be more effective to tweak the timing and context of daily activities than to focus solely on the total amount of calories consumed or burned. By leveraging the body’s natural rhythms and storing heat-generating adipose tissue, it becomes possible to nudge metabolism in a healthier, more energy-expending direction.

Future Directions and Open Questions

Despite the growing body of evidence that synchronizing daily habits with circadian rhythms can boost brown fat activity and improve metabolic health, many unanswered questions remain. One key area concerns the clinical translation of these findings into practical therapies. While small studies suggest that interventions like scheduled cold exposure, time-restricted eating, or melatonin supplementation can nudge the body toward a more energy-expending state, scientists have yet to determine how these strategies might be best combined or prescribed for individuals at high risk of metabolic disease. People with prediabetes, for instance, might benefit greatly from carefully timed exposure to cooler temperatures or strict meal windows if such measures consistently lower fasting glucose or enhance insulin sensitivity. However, implementing these protocols in real-world settings—especially with large, diverse populations—presents logistical and adherence challenges that have yet to be thoroughly explored.

A second open question involves gender differences. In Straat et al.’s investigation, men showed a distinctly larger jump in thermogenesis in the morning compared to the evening, whereas women’s metabolic responses were more balanced across time. At the same time, women’s blood markers indicated potentially greater fatty acid mobilization under certain conditions. The reasons behind these divergent responses could be rooted in hormonal factors, baseline variations in brown fat distribution, or even subtle differences in circadian gene expression. Pinpointing these mechanisms will be essential for designing targeted interventions that account for sex-based physiologies rather than assuming a one-size-fits-all approach.

Finally, there is a need for long-term studies that go beyond short-term markers like acute changes in energy expenditure or shifts in plasma lipids. While short-term improvements—such as enhanced non-shivering thermogenesis or modest weight reduction—are encouraging, it remains uncertain whether these gains can be maintained over months or years. Researchers must also clarify whether a sustained circadian-based protocol, anchored by strategies like cold exposure in the morning and consistent nighttime melatonin production, leads to enduring weight loss, durable improvements in insulin sensitivity, or a meaningful drop in long-term health risks. If the initial promise of circadian alignment holds up in multi-year clinical trials, it could mark a transformative step toward integrating chronobiology into mainstream preventive medicine.

Key Takeaways: Synchronizing Your Body Clock with Brown Fat for Better Health

It’s increasingly clear that managing our metabolism hinges not just on what we do but also on when we do it. By aligning brown fat activation with the body’s natural circadian peaks—especially in the morning, when both diet-induced and cold-induced thermogenesis appear most robust—we can amplify calorie burning, improve glucose and fat metabolism, and optimize various hormonal pathways. Equally critical is preserving a healthy nighttime rhythm. As demonstrated by human trials where melatonin supplementation restored normal nocturnal hormone profiles and reignited brown fat activity, ensuring adequate melatonin release can further boost thermogenesis. Collectively, these insights offer a novel, safe, and potentially impactful way to tackle chronic metabolic conditions. Whether through morning cold exposure, time-restricted eating, or deliberate management of light and dark cycles, leveraging our innate biological clock may be key to more effective weight control, enhanced insulin sensitivity, and better cardiometabolic health.

- Matsushita M, Nirengi S, Hibi M, Wakabayashi H, Lee SI, Domichi M, Sakane N, Saito M. Diurnal variations of brown fat thermogenesis and fat oxidation in humans. Int J Obes (Lond). 2021 Nov;45(11):2499-2505. doi: 10.1038/s41366-021-00927-x. Epub 2021 Aug 2. PMID: 34341470; PMCID: PMC8528701.

- Straat ME, Martinez-Tellez B, Sardjoe Mishre A, Verkleij MMA, Kemmeren M, Pelsma ICM, Alcantara JMA, Mendez-Gutierrez A, Kooijman S, Boon MR, Rensen PCN. Cold-Induced Thermogenesis Shows a Diurnal Variation That Unfolds Differently in Males and Females. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022 May 17;107(6):1626-1635. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgac094. PMID: 35176767; PMCID: PMC9113803.

- Halpern B, Mancini MC, Bueno C, Barcelos IP, de Melo ME, Lima MS, Carneiro CG, Sapienza MT, Buchpiguel CA, do Amaral FG, Cipolla-Neto J. Melatonin Increases Brown Adipose Tissue Volume and Activity in Patients With Melatonin Deficiency: A Proof-of-Concept Study. Diabetes. 2019 May;68(5):947-952. doi: 10.2337/db18-0956. Epub 2019 Feb 14. PMID: 30765337.