Plasmalogens and Cognitive Longevity: A Lipid-Centric Perspective on Dementia Risk

Vinyl Ether Bond: Plasmalogens are characterized by a vinyl ether bond at the sn-1 position of the glycerol backbone, differentiating them from more common phospholipids. This structural feature makes them exceptionally resistant to oxidative stress and confers potent free radical–scavenging properties.

Protective Role in Cell Membranes: By preferentially oxidizing at the vinyl ether bond, plasmalogens act as “sacrificial” molecules that absorb oxidative damage. This spares other membrane components—including critical phospholipids like cardiolipin and cholesterol—from peroxidation.

Influence on Membrane Fluidity: Their unique structure also affects how lipids pack together in the bilayer, enhancing membrane flexibility and stability, which is essential for maintaining cellular homeostasis under varying physiological conditions.

High Abundance in Key Tissues: Plasmalogens are concentrated in organs with high metabolic demand, such as the brain, heart, and skeletal muscle.

Neuronal Communication and Myelination: In the brain, these lipids foster efficient synaptic transmission and contribute to the formation and maintenance of myelin sheaths around nerve fibers. Healthy myelin promotes rapid signal conduction and protects neurons from damage.

Mitochondrial Support: Plasmalogens help stabilize cardiolipin, a specialized phospholipid in the inner mitochondrial membrane. This bolsters the electron transport chain, aiding ATP production and reducing harmful reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated during metabolism.

Cardiovascular Benefits: Beyond the brain, plasmalogens help regulate lipid efflux and reduce oxidative stress, potentially lowering the risk of atherosclerosis and other heart conditions.

Gradual Decrease Over Time: Plasmalogen levels typically begin to fall after midlife, with a sharper decline observed in older age. Peroxisomal dysfunction, oxidative stress, and dietary insufficiencies can exacerbate this process.

Association with Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s: Lower plasmalogen levels have been documented in patients with Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, suggesting a possible contributory role in disease pathogenesis. Reduced antioxidant capacity and poorer neuronal membrane integrity may accelerate β-amyloid and α-synuclein toxicity.

Reduced Dementia Risk in Individuals with High Plasmalogen Levels: One of the landmark observations from this cohort study was that older adults (e.g., those aged 85) with elevated plasmalogen levels showed a dementia risk comparable to younger adults (e.g., those aged 75) with lower levels.

Relevance for APOE4 Carriers: Individuals with the APOE ε4 allele often display reduced plasmalogen levels alongside impaired cholesterol transport and heightened risk for Alzheimer’s. Targeted therapies aimed at bolstering plasmalogen status may provide significant neuroprotection in this genetically susceptible group.

In 2019, the Rush University Memory and Aging Project revealed a compelling finding in its dementia research: an 85-year-old with elevated levels of a particular lipid exhibited the same risk of dementia as a 75-year-old with relatively lower levels of that same lipid. This observation raised a crucial question: could these lipids—known as plasmalogens—serve as a cornerstone of cognitive longevity?

Plasmalogens are a specialized class of phospholipids, found abundantly in the brain, heart, and other vital organs. Unlike more common phospholipids, they contain a vinyl ether bond, rendering them highly resistant to oxidative stress. Visualize them as reinforced bricks in cellular walls—providing essential structure while shielding cells from damage. By preferentially oxidizing at the vinyl ether bond, plasmalogens act as “sacrificial” molecules that absorb oxidative damage.

Given that oxidative damage is a major driver of cellular aging and neurodegeneration, the protective role of plasmalogens suggests that their decline with age could leave neurons increasingly vulnerable to dysfunction. A dwindling supply may contribute to the accumulation of oxidative stress, impairing synaptic activity and accelerating cognitive decline.

As a result, plasmalogen levels naturally decline with age, particularly within the brain, leading to potential consequences for cognitive and systemic health. This loss has been strongly associated with an increased risk of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, as well as cardiovascular issues and systemic inflammation.

In this research narrative review, we present a comprehensive examination of plasmalogens’ biochemical roles and their clinical relevance—elucidating how they function, why they diminish over time, and the interventions that may replenish these vital lipids to slow or possibly reverse aspects of aging and neurodegeneration.

What Are Plasmalogens?

Before exploring their role in brain health and disease, it is essential to understand what plasmalogens are, how they function at a molecular level, and why their loss may accelerate aging and cognitive dysfunction.

A Unique Class of Phospholipids

At first glance, plasmalogens resemble their more common phospholipid cousins. They share the familiar glycerol backbone, fatty acid chains, and a phosphate-containing head group, creating the classic design that allows them to form bilayers in cell membranes. But their vinyl ether bond sets them apart. This subtle structural twist dramatically enhances their antioxidant capacity and membrane fluidity, making plasmalogens crucial for cell protection and metabolic efficiency.

Imagine standard phospholipids as ordinary bricks in a wall. They hold things together, but under stress, they can crumble. Plasmalogens, by contrast, are like fortified bricks, containing a built-in defense system that prevents them—and by extension, the cell membrane—from succumbing to oxidative “rust”. This structural advantage gives plasmalogens a distinctive role in protecting cells against the relentless bombardment of reactive oxygen species (ROS).

One striking feature of plasmalogens is where they are made. Their production begins in peroxisomes, specialized organelles often described as miniature biochemical factories for lipid metabolism. There, a precursor called dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) undergoes multiple enzymatic steps to become a plasmalogen intermediate. The process finishes in the endoplasmic reticulum, yielding the fully formed plasmalogen that is then inserted into cell membranes.

If these factories don’t work correctly, plasmalogen levels drop, leading to widespread issues in the body, especially in the brain and nervous system, which rely on these molecules for protection and function.

Individuals with peroxisomal disorders often exhibit severely reduced plasmalogen levels, leading to neurological impairments and systemic dysfunctions. In other words, when peroxisomes don’t function properly, the body struggles to make plasmalogens, resulting in problems like muscle weakness, developmental delays, and cognitive decline. The brain and nervous system depend highly on plasmalogens to keep neurons healthy and ensure smooth cell communication. Without enough plasmalogens, signals between brain cells slow down, increasing the risk of neurodegenerative diseases. This underscores their indispensable role in cellular health, signaling, and protection against oxidative stress.

Plasmalogens are Key Structural Components

Plasmalogens excel at reinforcing cell membranes when conditions turn hostile—whether due to oxidative stress, mechanical strain, or metabolic byproducts. To envision how they do this, think of a cell membrane as a balloon: it needs enough flexibility to adapt to changing pressures but must remain sturdy to avoid ruptures. Plasmalogens help fine-tune this balance by integrating into the lipid bilayer, where their distinctive vinyl ether bond influences both fluidity and stability.

From a biochemical standpoint, membrane fluidity depends on how tightly lipid molecules pack together. The double bonds and ether linkage in plasmalogens create slight kinks and altered electronic configurations, preventing the rigid stacking of fatty acid tails. This spacing effect fosters a more adaptable membrane—one capable of withstanding the rapid shifts in temperature, pH, and oxidative conditions seen in high-energy organs like the brain and heart. Additionally, their polar head groups help maintain proper hydrophilic (water-attracting) and hydrophobic (water-repelling) balance, further strengthening the membrane against external stressors.

Yet, maintaining membrane stability isn’t just about elasticity. It also requires protection against lipid peroxidation, a destructive chain reaction initiated by reactive oxygen species (ROS). In scientific terms, once a free radical attacks an unsaturated lipid in the bilayer, it forms lipid radicals that, in turn, target neighboring lipids. This process can escalate like a row of dominoes, swiftly compromising membrane integrity and leading to the creation of toxic byproducts.

Plasmalogens serve as molecular “blockers” in this sequence. Their vinyl ether bond is strategically prone to oxidation, meaning it preferentially reacts with free radicals before they can damage other membrane components. By sacrificing themselves in this way—similar to a firebreak halting a spreading blaze—plasmalogens effectively terminate the peroxidation chain reaction. This built-in protective mechanism prevents further harm to critical lipids like cardiolipin, which is essential for mitochondrial function, or cholesterol, which supports membrane structure and hormone synthesis.

Moreover, by neutralizing the initial surge of free radicals, plasmalogens reduce the secondary inflammatory responses that often accompany lipid peroxidation. Inflammation-inducing molecules, including various cytokines, are less likely to proliferate when oxidative stress is kept in check. As a result, the presence of ample plasmalogens in neuronal membranes and cardiac cells can help maintain not only membrane integrity but also overall cellular homeostasis during periods of stress.

In short, plasmalogens act as both architects and defenders of membrane structure. They mold the bilayer to remain sufficiently fluid for cell signaling and nutrient transport, while shielding it from the damaging effects of uncontrolled oxidation. This dual role is particularly vital in organs that demand high metabolic output, like the brain, where tiny disruptions in membrane dynamics can have outsized effects on cognition, and the heart, where even minor impairments can jeopardize cardiovascular function.

Scavenging Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

While plasmalogens reinforce the physical structure of cell membranes, their true hallmark may be their capacity to neutralize reactive oxygen species (ROS)—byproducts of normal metabolism that can spiral out of control when produced in excess. Chronic oxidative stress has long been implicated in a host of conditions, from neurodegenerative diseases to cardiovascular disorders and metabolic syndromes. By carrying a vinyl ether bond, plasmalogens act as molecular shock absorbers, drawing the oxidative strike toward themselves and sparing more vulnerable lipids and proteins from damage.

Beyond directly intercepting free radicals, plasmalogens appear to regulate wider redox homeostasis. Studies indicate that a healthy plasmalogen pool may help curb the activity of pro-inflammatory signaling pathways, such as NF-κB, which can be activated by unrestrained ROS levels. By lowering overall oxidative burden, plasmalogens potentially reduce the downstream release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, limiting damage to surrounding tissues and preserving cellular function.

Just as crucially, plasmalogens collaborate with the cell’s existing antioxidant arsenal, including glutathione—the body’s master detoxifier—and superoxide dismutase (SOD), which disarms a particularly reactive form of oxygen called the superoxide radical. Research suggests that adequate plasmalogen levels may help maintain optimal glutathione cycling, ensuring that glutathione stays in its active, reduced form and can continue repairing oxidative harm throughout the cell. By absorbing the initial oxidative hit, plasmalogens lessen the burden on these antioxidant systems, effectively prolonging their functional capacity.

Furthermore, emerging evidence points to a link between plasmalogen deficiency and elevated oxidative biomarkers in certain disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease and diabetic complications. This correlation underscores the broader physiological importance of plasmalogens in minimizing oxidative damage across multiple organ systems—not just the brain. In this way, plasmalogens act as coordinators of cellular defense, bridging the gap between membrane resilience and the enzymatic antioxidant network that keeps cells functioning smoothly even under metabolic duress.

By reinforcing the body’s built-in defenses, plasmalogens help ensure that a spike in ROS—whether from intense exercise, environmental toxins, or normal aging—doesn’t escalate into widespread oxidative damage. In essence, they buy time for other antioxidant molecules to do their job and maintain the delicate balance that keeps our cells from tipping into chronic inflammation and dysfunction.

Mitochondrial Support & Energy Production

Plasmalogens also play a pivotal role in helping cells meet their continuous energy demands, largely by optimizing mitochondrial function. Often described as the “powerhouses of the cell,” mitochondria convert nutrients into adenosine triphosphate (ATP)—the chemical fuel that drives nearly every biological process. Yet this transformation comes at a cost: mitochondria must operate under high metabolic flux, where even small perturbations in membrane composition can compromise energy output.

Stabilizing the Electron Transport Chain

A central aspect of plasmalogens’ influence on mitochondrial efficiency lies in their support of the electron transport chain (ETC). This series of protein complexes, situated in the inner mitochondrial membrane, orchestrates the sequential transfer of electrons that culminates in ATP generation. Any disruption in the organization of these complexes can lower ATP yield and increase the leakage of electrons—a phenomenon associated with excess reactive oxygen species (ROS) production.

- Maintaining Cardiolipin Integrity: By bolstering cardiolipin, a specialized phospholipid critical for ETC stability, plasmalogens help preserve the conformation of ETC proteins. Studies suggest that altered or insufficient cardiolipin can hinder the formation of supercomplexes (aggregates of ETC complexes), thereby impairing electron flow and reducing the efficiency of ATP synthesis. Plasmalogens, through their distinct molecular structure, may minimize cardiolipin oxidation and keep these supercomplexes functionally intact.

- Promoting Electron Flux: Beyond merely “holding” ETC complexes in place, plasmalogens contribute to a membrane environment that reduces electron leak. This controlled environment lessens the formation of superoxide radicals—an especially reactive type of ROS—thereby conserving energy for ATP production rather than diverting it into damage control.

Enhancing Fatty Acid Utilization

Plasmalogens also support energy metabolism by facilitating fatty acid utilization. During periods of fasting, exercise, or low carbohydrate intake, cells increasingly rely on beta-oxidation to convert stored fats into acetyl-CoA, which then enters the TCA (Krebs) cycle to produce ATP. Research indicates that lipid membrane composition can modulate the activity of enzymes involved in these metabolic pathways.

- Optimizing Enzymatic Activity: By integrating into mitochondrial membranes, plasmalogens can stabilize the enzyme complexes that regulate the transport and breakdown of fatty acids. This ensures steady substrate flow, enabling cells to tap into fat reserves efficiently—a key advantage for endurance and metabolic flexibility.

- Sustaining Cellular Energy Output: With beta-oxidation functioning at peak levels, plasmalogens help maintain an ample supply of ATP over extended periods. This can translate to improved endurance during physical exertion, reduced reliance on glucose stores, and more robust energy availability for high-demand tissues like the brain and muscles.

Protecting Mitochondrial DNA and Proteins

While oxidative stress has been discussed in broader terms, mitochondria have their own genetic material (mtDNA) and a unique set of proteins. The inner mitochondrial membrane is densely packed with the machinery for ATP production, making it a hot spot for oxidative byproducts.

- Localizing Defense: The presence of plasmalogens in this membrane region can contain ROS generated as a natural byproduct of the ETC. By neutralizing reactive species closer to their source, plasmalogens help prevent damage to mtDNA—whose stability is crucial for the ongoing synthesis of ETC components—and key mitochondrial proteins responsible for ATP synthesis and ion transport.

- Supporting Mitochondrial Quality Control: Emerging evidence suggests that membrane lipid composition can influence mitophagy (the selective removal of damaged mitochondria). By maintaining a healthier mitochondrial membrane profile, plasmalogens may indirectly enhance the cell’s ability to identify and recycle dysfunctional mitochondria, preserving overall metabolic efficiency.

The ability of plasmalogens to shore up mitochondrial function and preserve energy production becomes particularly significant when we consider the brain’s intense metabolic demands. Neurons are voracious consumers of ATP, and any compromise in their energy supply or membrane integrity can undermine synaptic communication and accelerate neurological decline.

It is here—at the crossroads of high energy needs and long-term neural protection—that the role of plasmalogens becomes especially compelling. Research by neuroscientist and biochemist Dr. Dayan Goodenowe has provided more context of how these specialized lipids not only support synaptic function and neurotransmitter release but may also protect against the very processes that drive age-related neurodegeneration.

Plasmologens, Cognitive Health, and Neurodegenerative Diseases

When Dr. Goodenowe noticed that healthy older adults often maintained higher levels of certain lipids in their brains, he began to suspect that these molecules—plasmalogens—might be doing more than simply strengthening cell membranes. Over years of research, he and other scientists found that plasmalogens actually play a pivotal role in protecting cognitive function and fending off neurological decline. [1]

Synaptic Function and Neurotransmission

One of the brain’s most critical tasks is efficient communication between neurons, and that largely hinges on the health of synapses—the tiny gaps across which neurotransmitters pass. Plasmalogens appear to fortify these neural junctions by enhancing membrane flexibility, allowing signals to flow seamlessly. In particular, they help ensure the steady release of acetylcholine, a chemical messenger that underpins learning, memory formation, and recall. When acetylcholine levels drop, cognitive processes slow—a hallmark of conditions like Alzheimer’s disease. Thus, maintaining high plasmalogen levels could mean better neural “conversation” and a greater defense against memory decline.

β-Amyloid Clearance and Tau Stability

Beyond aiding everyday brain function, plasmalogens also protect neurons from two notorious threats in Alzheimer’s disease: β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques and tau tangles. β-amyloid fragments originate from the abnormal cleavage of amyloid precursor protein (APP) and can aggregate outside neurons, interfering with synaptic communication. Meanwhile, tau proteins, which normally stabilize microtubules inside cells, can become hyperphosphorylated, twisting into filamentous tangles that disrupt intracellular transport and weaken cell architecture.

Plasmalogens appear to support the cell’s innate pathways for eliminating these toxic proteins. One proposed mechanism involves maintaining the membrane fluidity and integrity required for efficient vesicular transport and endocytosis—processes by which cells internalize and degrade β-amyloid peptides. Studies also suggest plasmalogen-rich membranes can enhance or organize certain receptor proteins involved in Aβ uptake, helping neurons and glial cells recognize and clear the accumulating fragments. [1]

Although more research is needed, some scientists hypothesize that higher plasmalogen levels may help optimize the glymphatic system—the brain’s waste-clearance mechanism that flushes out β-amyloid during sleep. By preserving the structural integrity of perivascular channels, plasmalogens could facilitate the flow of cerebrospinal fluid, improving toxin clearance in the extracellular environment.

Collectively, these roles position plasmalogens as potential mediators of “brain housekeeping,” spanning membrane-level maintenance, protein trafficking, and waste disposal. Indeed, clinical observations often link low plasmalogen levels with higher β-amyloid deposition and more advanced tau pathology in Alzheimer’s patients—suggesting that restoring or augmenting plasmalogens may slow or mitigate disease progression.

In addition to these protective effects, plasmalogens are potent antioxidants that shield neurons from oxidative stress. Their unique vinyl-ether bond makes them highly effective at neutralizing harmful molecules, preventing oxidative damage, and maintaining neuron integrity. This built-in antioxidant defense helps reduce inflammation and protect the brain from age-related decline.

Myelin Function: Supporting Nervous System Health and Signal Transmission

Plasmalogens play a critical role in nerve insulation and communication, helping ensure that signals travel rapidly and efficiently along the nervous system’s extensive network. They are integral to the myelin sheath—a protective layer encasing nerve fibers that functions much like insulation around electrical wires. When myelin is compromised, neural impulses are slowed or disrupted, contributing to serious neurological conditions such as multiple sclerosis (MS) and various neurodegenerative diseases.

One of plasmalogens’ primary contributions is to reinforce and regenerate the myelin sheath. This sheath is composed of specialized lipids and proteins, with plasmalogens acting as key structural components that promote both stability and resilience. Think of myelin as a high-grade protective coating on a data cable—if it’s damaged, signals degrade, leading to impaired communication between neurons. By stabilizing myelin architecture, plasmalogens support smooth, high-speed transmission of nerve impulses and assist in recovery from everyday wear and tear.

Importantly, plasmalogens also help ward off demyelination, a process in which the myelin sheath breaks down due to oxidative stress, inflammation, or autoimmune attacks. In conditions like MS, the immune system mistakenly targets and destroys myelin, often resulting in muscle weakness and cognitive difficulties. By acting as potent antioxidants and modulators of inflammation, plasmalogens reduce oxidative damage and inhibit inflammatory mediators that contribute to myelin breakdown. This protective environment can lower the risk of progressive neurodegeneration and curb further loss of myelin.

Beyond immediate protection, plasmalogens enhance nerve plasticity and repair mechanisms, ensuring the nervous system can adapt and recover from injury or disease. They support oligodendrocytes—the cells responsible for producing and maintaining myelin—helping them stay efficient even as the body ages or experiences stress. By keeping oligodendrocytes in top form, plasmalogens facilitate continuous myelin maintenance and regeneration, underlining their value for lifelong neurological health. [1, 2]

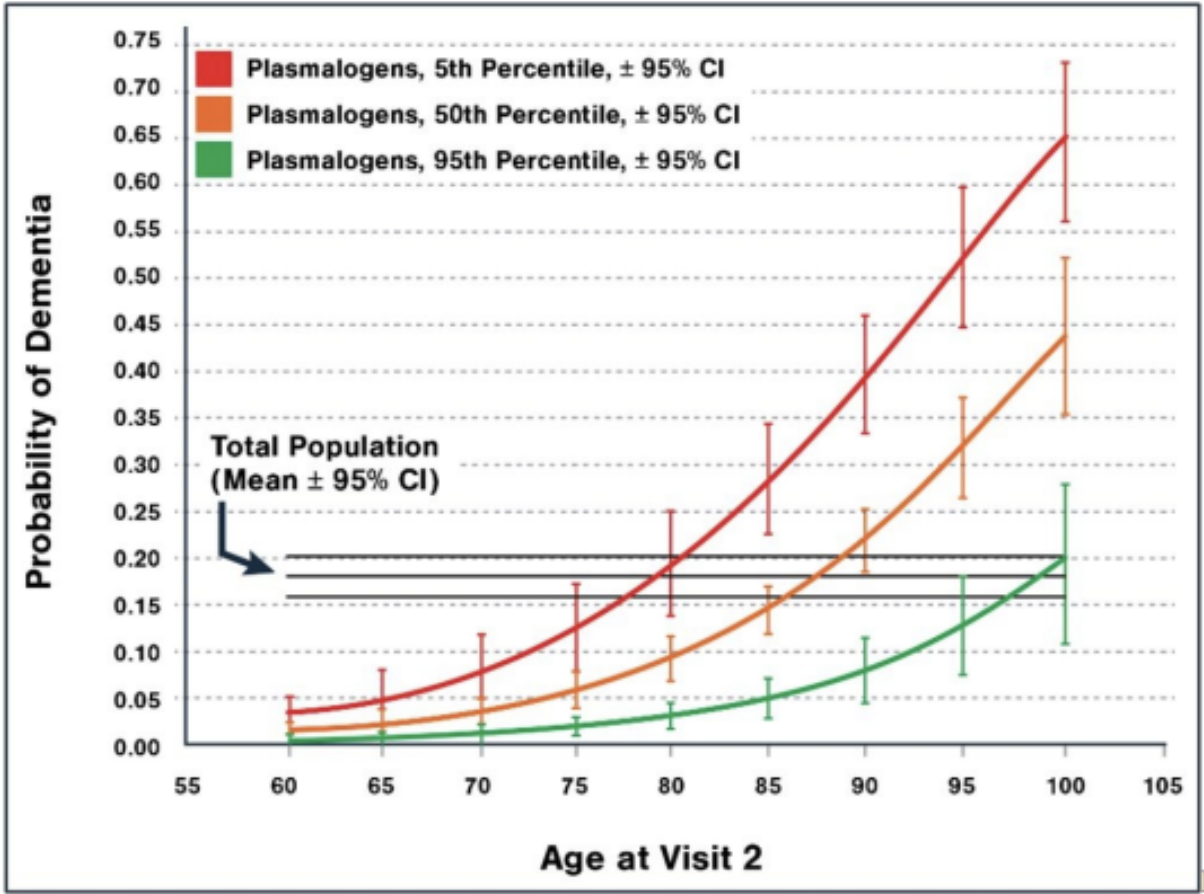

Association Between Blood Plasmalogen Levels, Age, and the Probability of Dementia

A study conducted by the Rush University Memory and Aging Project examined the relationship between blood plasmalogen levels, age, and the likelihood of developing dementia. The study compared individuals with high, average, and low plasmalogen levels to assess how these differences impacted cognitive health across different age groups. The results are shown in the graph below. They illustrate how higher blood plasmalogen levels may be associated with a lower probability of developing dementia, reinforcing their potential role as a biomarker for cognitive health and a target for neuroprotective interventions.

Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between blood plasmalogen levels, age, and the probability of developing dementia. An 85-year-old with high plasmalogen levels had only a 5% chance of having dementia. In contrast, an 85-year-old with average plasmalogen levels had a 14% chance, and an 85-year-old with low plasmalogen levels had a significantly higher risk at 28%. Additionally, the data shows that a 95-year-old with high plasmalogen levels had the same likelihood of developing dementia as a 75-year-old with low plasmalogen levels, emphasizing the potential protective role of plasmalogens in cognitive aging. This figure highlights the importance of plasmalogen levels as a possible biomarker for dementia risk and suggests that maintaining higher plasmalogen levels may help preserve cognitive function over time. [1]

The Latest Research on Plasmalogens and Cognitive Impairment

Plasmalogens play a critical role in brain health and longevity by supporting neuronal function, protecting against oxidative damage, and reducing neuroinflammation. These specialized phospholipids are essential for maintaining synaptic integrity, enhancing neurotransmission, and preventing β-amyloid accumulation—three key factors in developing neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

As natural plasmalogen levels decline with age—particularly after 50—the brain becomes more vulnerable to oxidative stress and inflammation, two major drivers of cognitive decline. Plasmalogens act as powerful antioxidants, shielding brain cells from damage, supporting mitochondrial energy production, and maintaining myelin integrity, essential for efficient neural communication.

This decline is even more pronounced in individuals with neurodegenerative conditions, where accelerated plasmalogen depletion has been observed. Low plasmalogen levels have been linked to:

- Cognitive decline and memory loss

- Increased oxidative stress and chronic inflammation

- A higher risk of cardiovascular diseases

Conversely, studies consistently show that higher plasmalogen levels are associated with improved memory, better cognitive function, and a reduced risk of neurodegenerative diseases. As research continues to uncover their significance, plasmalogens are emerging as a promising target for interventions to preserve brain health and slow age-related decline. [1, 2]

Role of Plasmalogen Levels in APOE4 Carriers

Of the many genetic factors linked to Alzheimer’s disease, one stands out as the strongest and most well-documented: the APOE ε4 allele. Individuals carrying one or two copies of APOE4 are at significantly higher risk for cognitive decline and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. This heightened susceptibility is not due to a single mechanism but rather a cascade of disruptions in lipid metabolism, synaptic function, and neuroprotection—many of which are closely tied to plasmalogen biology.

ApoE4 carriers exhibit altered cholesterol transport and lipid homeostasis, leading to impaired cholesterol efflux from neurons and glial cells. This dysfunction affects not only membrane integrity but also cardiovascular health, further compounding neurodegenerative risk. Unlike ApoE3, which facilitates a well-regulated lipid transport system, ApoE4 mismanages cholesterol recycling, creating imbalances in brain lipid metabolism, increasing oxidative stress, and ultimately compromising neuronal resilience. In the brain, this failure to properly recycle cholesterol leads to disruptions in synaptic plasticity, neuronal repair, and the clearance of neurotoxic β-amyloid peptides—all of which converge to increase the likelihood of Alzheimer’s and cognitive decline.

Building on the well-established link between APOE4 and Alzheimer’s risk, researchers have begun uncovering a critical biochemical connection: lower plasmalogen levels in APOE4 carriers may contribute directly to neurodegeneration. A study by Dr. Goodenowe titled Relation of Serum Plasmalogens and APOE Genotype to Cognition and Dementia in Older Persons in a Cross-Sectional Study found that lower serum plasmalogen levels correlate with cognitive impairment and dementia. Additionally, individuals carrying the APOE ε4 allele exhibited reduced plasmalogen levels. These findings suggest that decreased plasmalogen levels may contribute to cognitive decline. The APOE ε4 genotype may influence plasmalogen metabolism, potentially offering a biomarker for early detection of cognitive impairment and dementia. [3]

Plasmalogens seem to regulate multiple processes that intersect with APOE4-related vulnerabilities. Specifically, by facilitating reverse cholesterol transport, plasmalogens help counteract ApoE4’s impaired lipid trafficking, ensuring that cholesterol is properly redistributed for synaptic maintenance and repair. In parallel, plasmalogens contribute to β-amyloid clearance, potentially mitigating one of APOE4’s most damaging effects: the accumulation of neurotoxic amyloid plaques. Plasmalogens also supply DHA (docosahexaenoic acid)—a crucial structural component that nourishes brain gray matter, strengthens synapses, and ensures smooth neuromuscular communication. When plasmalogen levels drop, the entire system becomes strained, accelerating APOE4-driven neurodegeneration.

Plasmalogens and Other Neurodegenerative Conditions

Plasmalogens are increasingly recognized for their potential role in various neurodegenerative and neurological conditions, including Parkinson’s disease (PD), multiple sclerosis (MS), and autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Research in Parkinson’s disease suggests that plasmalogens help protect dopaminergic neurons from oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation, both of which contribute to disease progression. Studies indicate that plasmalogen levels are significantly reduced in PD patients, and supplementation may support mitochondrial function and reduce neuroinflammation, key factors in slowing disease progression.

Plasmalogens are crucial in myelin integrity in multiple sclerosis (MS). They are a fundamental component of the myelin sheath that insulates neurons. MS is characterized by demyelination and chronic inflammation, and studies suggest that low plasmalogen levels correlate with disease severity. Restoring plasmalogen levels may promote remyelination, reduce inflammation, and support immune system balance, potentially improving neurological function in MS patients.

Research in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) also points to a link between plasmalogen deficiency and impaired neurodevelopment. Plasmalogens are involved in synaptic function, neurotransmitter regulation, and neural connectivity, all of which are altered in ASD. Some studies suggest that children with autism have lower plasmalogen levels, which may contribute to oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and altered lipid metabolism in the brain. Researchers are investigating whether plasmalogen supplementation could enhance cognitive function, reduce inflammation, and improve behavioral outcomes in ASD individuals.

Plasmalogens appear to be a critical factor in neuroprotection, mitochondrial health, and inflammation control across multiple neurological disorders. While more clinical trials are needed, research suggests that restoring plasmalogen levels may be a promising strategy for supporting brain health and reducing neurodegeneration.

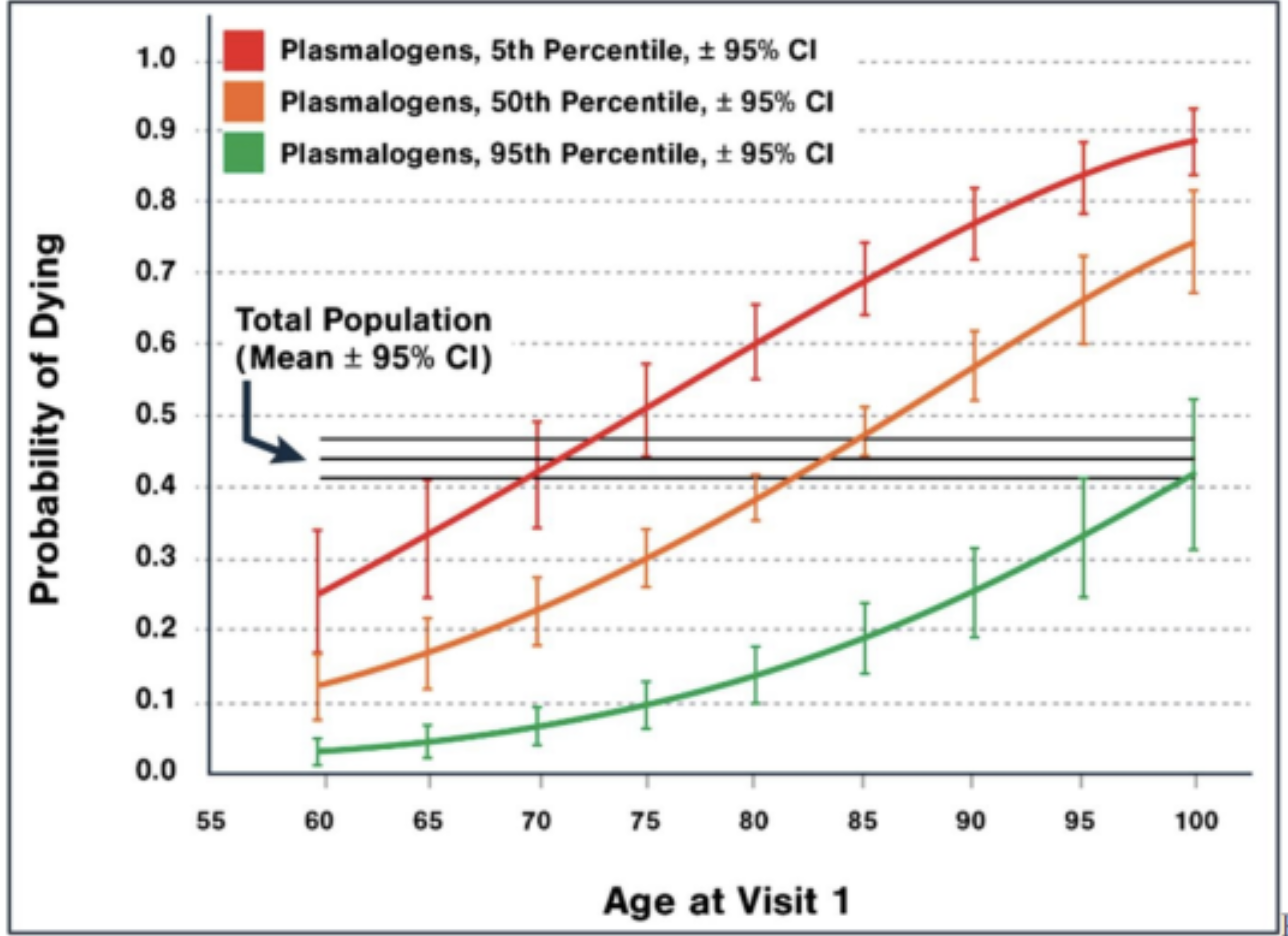

Plasmalogens’ Impact Beyond Neurological Health

While most research on plasmalogens focuses on their role in neurological health, several studies have also identified their benefits in other body areas. Studies have found that plasmalogen levels are linked to overall mortality. The figure below highlights the strong association between plasmalogen levels, age, and long-term survival. Regardless of sex or dementia status, a 95-year-old with high plasmalogen levels has the same 5.3-year mortality risk as a 65-year-old with low plasmalogen levels, suggesting that higher plasmalogen levels may be a marker of biological resilience. While these benefits may be linked to the neuroprotective benefits of plasmalogens, there may be a link between other bodily systems.

Figure 2. This figure demonstrates that, regardless of sex or dementia status, a 95-year-old with high plasmalogen levels has the same 5.3-year mortality risk as a 65-year-old with low plasmalogen levels. Additionally, a 95-year-old with high plasmalogen levels has nearly a 70% chance of reaching 100, whereas a 95-year-old with low plasmalogen levels has less than a 20% chance of achieving the same longevity. [1]

Plasmologens and Cardiovascular Health

Some of plasmalogens' benefits may also come from their role in maintaining heart and blood vessel health, helping to regulate cholesterol balance, protecting arteries, and reducing inflammation that can contribute to cardiovascular disease. Since heart disease is often driven by oxidative stress, cholesterol imbalances, and inflammation, plasmalogens are a natural defense mechanism, supporting overall cardiovascular function and longevity.

One of their main benefits is regulating cholesterol and lipid efflux, which refers to how cholesterol is transported and removed from the body. Plasmalogens support the function of high-density lipoprotein (HDL), often referred to as "good cholesterol," which helps transport excess cholesterol away from the arteries and back to the liver for disposal. At the same time, plasmalogens help reduce low-density lipoprotein (LDL) oxidation—a key factor in developing heart disease. When LDL cholesterol oxidizes, it can stick to artery walls and form plaques, increasing the risk of blockages and heart attacks. By preventing this oxidation, plasmalogens help keep arteries clear and blood flowing smoothly.

In addition to cholesterol regulation, plasmalogens enhance vascular protection and nitric oxide (NO) modulation, which improves blood vessel elasticity and reduces arterial stiffness. The endothelium, the thin layer of cells lining blood vessels, produces nitric oxide—a molecule that relaxes blood vessels and allows blood to flow freely. Plasmalogens support endothelial function by ensuring a steady release of nitric oxide, preventing blood vessels from becoming stiff and reducing strain on the heart. Think of nitric oxide as the body's natural way of widening highways to ease traffic—when nitric oxide levels are high, blood moves smoothly, lowering the risk of high blood pressure and heart disease.

Plasmalogens also have anti-inflammatory effects in the arteries, reducing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines—molecules that contribute to chronic inflammation and atherosclerosis (the buildup of plaques in the arteries). When cytokine levels are too high, the immune system mistakenly attacks healthy blood vessel walls, leading to thickening and hardening of the arteries. By lowering inflammation, plasmalogens help prevent this damage, keeping arteries flexible and reducing the risk of heart disease, strokes, and other cardiovascular complications.

Challenges in Plasmalogen Absorption

Healthy brains have higher plasmalogen reserves, which protect them from neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. Building these reserves takes decades and can be lost quickly when exposed to excessive inflammation, injury, or toxins.

Brain cells must restore and maintain these reserves, specifically the peroxisomes in neurons and oligodendrocytes. The optimal way to enhance plasmalogen levels in the brain is to provide these cells with pre-made plasmalogen precursors, along with exercise, fasting, and proper nutrition.

Despite their importance, dietary intake of plasmalogens is insufficient to replenish depleted levels. While some dietary plasmalogens are absorbed, levels in food are often too low to replenish what the body needs—especially in aging or disease. Plasmalogen precursors—such as those developed by Prodrome Sciences—are viable for addressing this issue. These precursors are designed for optimal absorption and assimilation, ensuring effective restoration of plasmalogen levels in tissues, including the brain and heart. Plasmalogen precursor supplementation is scientifically proven to enable the brain to maintain integrity even during exposure to toxic demyelinating and neurodegenerative toxins. [2]

Supplements to Build Your Plasmalogen Reserve

- ProdromeGlia supports brain health by enhancing glial cell function and reducing neuroinflammation. It is generally recommended to start with ProdromeGlia for one week at a dose of ½ - 1 tsp daily. This product is very calming and relaxing, so it is best to take it at night.

- ProdromeNeuro targets overall neuronal health, improving synaptic function and antioxidative defenses. After 1-4 weeks on ProdromeGlia, add the Prper day. This is more energizing and turns the brain on, so taking it in the morning is best.

- Most people need at least 3-4 months to build their plasmalogen reserves and can continue to maintain them long-term over time. [1]

Conclusion: Plasmalogens as a Target for Healthy Aging

The growing body of plasmalogen research highlights their critical role in brain function, cardiovascular health, mitochondrial efficiency, and immune regulation. These specialized lipids serve as a structural foundation for cell membranes, protect against oxidative stress, and support efficient neural communication. Their decline with age has been strongly linked to neurodegeneration, cognitive impairment, and an increased risk of age-related diseases, making them a promising target for longevity interventions.

The evidence suggests that maintaining optimal plasmalogen levels may not only protect against conditions like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease but also enhance overall resilience to aging-related decline. Studies have demonstrated a clear association between higher plasmalogen levels and lower dementia risk, improved cognitive function, and even increased lifespan, reinforcing their significance as a biomarker for health and longevity.

Despite their importance, plasmalogen depletion remains a challenge due to limited dietary sources and natural age-related reductions. However, innovations in plasmalogen precursor supplementation offer a viable solution for replenishing and sustaining these essential lipids. Individuals may support brain health, metabolic function, and long-term vitality by incorporating strategies such as plasmalogen supplementation, exercise, fasting, and a nutrient-rich diet.

As research expands, plasmalogens are emerging as a critical tool for extending healthspan and preventing age-related diseases.

Want to Learn More?

- Schedule a Consult: To discuss how plasmalogens may support your longevity strategy, email

- Further Reading: For insights into the aging brain, cognitive decline, Alzheimer’s, and frailty, see this in-depth lecture.

- Goodenowe, D. B., & Senanayake, V. (2019). Relation of serum plasmalogens and APOE genotype to cognition and dementia in older persons in a cross-sectional study. Brain Sciences, 9(4), 92.

- Senanayake, V., & Goodenowe, D. B. (2019). Plasmalogen deficiency and neuropathology in Alzheimer's disease: Causation or coincidence? Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions, 5, 524-532.

- Wood, P. L., Mankidy, R., Ritchie, S., Heath, D., Wood, J. A., Flax, J., & Goodenowe, D. B. (2010). Circulating plasmalogen levels and Alzheimer Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive scores in Alzheimer patients. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience, 35(1), 59-62.

- Goodenowe, D. B., Cook, L. L., Liu, J., Lu, Y., Jayasinghe, D. A., Ahiahonu, P. W., Heath, D., Yamazaki, Y., Flax, J., Krenitsky, K. F., Sparks, D. L., Lerner, A., Friedland, R. P., Kudo, T., Kamino, K., Morihara, T., Takeda, M., & Wood, P. L. (2007). Peripheral ethanolamine plasmalogen deficiency: A logical causative factor in Alzheimer's disease and dementia. Journal of Lipid Research, 48(11), 2485-2498. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.P700023-JLR200