Reevaluating Midlife Metabolic Decline: A Four-Factor Framework Integrating Muscle, Mitochondrial Function, Hormones, and Inflammation

Introduction

We often hear that once you blow out the candles on your 30th (or 40th) birthday, your metabolism slams on the brakes. Conventional wisdom holds that the “middle-age spread” is simply an unavoidable part of getting older. Yet a growing body of research reveals a far more nuanced picture, including recent work published by the American Society for Clinical Investigation.

Yes, metabolism does tend to slow with age, but not merely because the candles on your cake keep multiplying. In fact, metabolic rate arises from a delicate balance in muscle mass, mitochondrial efficiency, hormones, and inflammation, all of which can shift in surprising ways over time. When the body’s metabolic engine starts sputtering—whether it’s from underperforming mitochondria or creeping insulin resistance—that could be the first sign of deeper imbalances.

Further complicating this narrative are several misconceptions that exist about metabolism. One such misconception is that menopause single-handedly derails a woman’s metabolism. While menopause does influence fat distribution and appetite regulation, it is not necessarily the main driver of midlife metabolic slowdowns. Recent studies suggest that the age-related decline in resting metabolic rate (RMR) is largely independent of menopause. Similarly, the belief that metabolism nosedives in early adulthood is increasingly at odds with large-scale human energy expenditure studies.

Two landmark investigations challenge the notion of a steep midlife metabolic decline, showing instead that metabolism stays far more stable into adulthood than previously assumed. The first, Daily Energy Expenditure through the Human Life Course, led by Dr. Herman Pontzer and colleagues, analyzed thousands of individuals across various age groups to reveal that total daily energy expenditure often remains steady from early adulthood until about age 60. The second, Metabolic Changes in Aging Humans: Current Evidence and Therapeutic Strategies, by Palmer and Jensen at the Mayo Clinic, highlights how hormonal shifts, organ size reductions, and chronic low-grade inflammation can further erode resting metabolic rate beyond what can be explained by muscle loss alone. Below, we explore why these findings diverge from conventional wisdom and examine what the data show about when—and how—our metabolic machinery begins to slow. Pinpointing these root causes of metabolic dysfunction opens the door to precisely targeted interventions.

A Brief Primer on TEE, BMR, RMR, and the Thermic Effect of Food

When discussing human metabolism, four concepts often arise: total daily energy expenditure (TEE), basal metabolic rate (BMR), resting metabolic rate (RMR), and the thermic effect of food (TEF). Energy expenditure science can feel alphabet-soup–heavy, so let’s clarify these key terms in more depth:

- Total Daily Energy Expenditure (TEE): TEE is the total energy (calories) you burn in 24 hours. It encompasses every energy-demanding process in your body—from keeping your heart pumping to walking the dog. In other words, TEE is the sum of all calories you burn in a day—this includes everything from keeping your organs running (which we generally call BMR or RMR) to the energy cost of digesting your meals (the TEF) and the calories used during physical activity or exercise.

- Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR): BMR is the minimum energy your body needs to support vital functions at complete rest—heartbeat, breathing, cellular repair, brain function—in a true baseline condition. It’s measured under very controlled circumstances: after waking up from at least 8 hours of sleep, in a fasted state, lying quietly in a temperature-controlled room. Because BMR accounts for about 50–70% of TEE in a typical adult, small changes in BMR can impact overall metabolism. The gold standard for measuring BMR is indirect calorimetry, where you breathe into a device that measures oxygen intake and carbon dioxide output, which can be converted into the calories you burn at rest.

- Resting Metabolic Rate (RMR): RMR is similar to BMR but is measured under less strict conditions—perhaps you’ve had a light rest (not necessarily 8 hours of sleep) or are sitting quietly instead of lying in a bed. RMR tends to be slightly higher than BMR (~5–10%) because it may reflect minor activities like being awake and seated. Nonetheless, many studies (and clinicians) use RMR and BMR almost interchangeably to indicate baseline metabolic rate.

- Thermic Effect of Food (TEF): Every time you eat, your body expends energy to chew, digest, absorb, transport, and store nutrients. This post-meal energy expenditure is called the thermic effect of food. TEF generally contributes about 10% of total daily energy expenditure. However, it can vary based on meal composition (protein has a higher thermic effect than fats or carbohydrates) and individual metabolic differences.

Large-Scale Evidence From Doubly Labeled Water Studies

In a recent study, Professor Herman Pontzer’s team at the Duke Global Health Institute assembled data from over 6,600 people, ranging in age from a few days to 95 years, across 29 countries. They employed the doubly labeled water (DLW) method, currently the best technique for capturing an individual’s total energy expenditure (TEE) in real-world conditions. Because TEE naturally includes basal metabolism, activity, and the thermic effect of food, the researchers could tease apart how daily caloric burn changes once adjusted for body size (e.g., muscle mass) and age-related factors. [1]

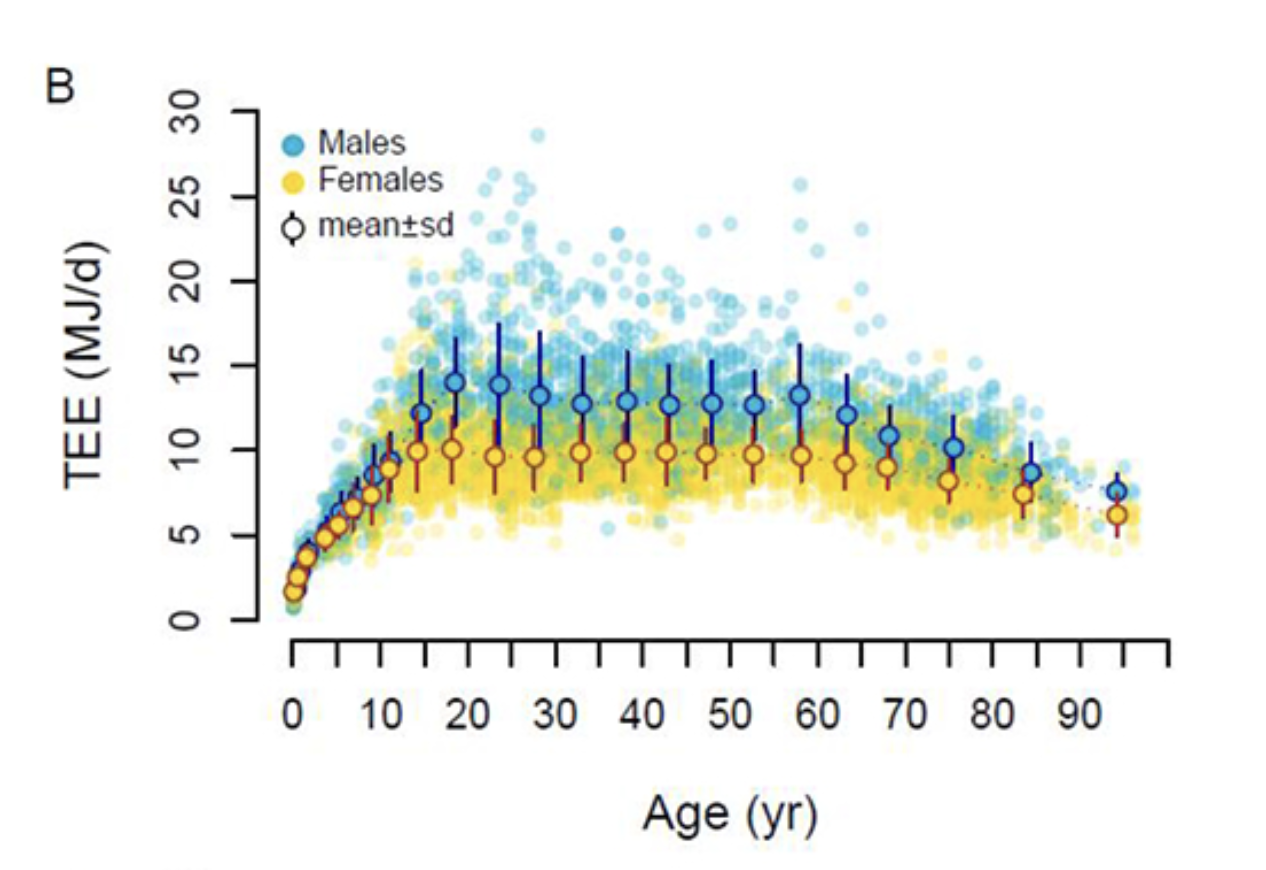

The research showed that metabolism changes over four distinct life changes. Newborns have particularly high, size-adjusted energy demands, peaking around 50% above adult levels in the first year. From ages 1 to 20, daily energy expenditure (per unit body weight) gradually declines until it stabilizes at “adult” levels. Contrary to popular belief, it stays there from about 20 until roughly 60. Only around age 60 does energy expenditure begin a steady decline of about 0.7% per year, culminating in about 26% fewer calories burned by one’s 90s than midlife. [1]

This late-life drop involves more than just losing muscle: the body’s underlying cellular machinery also appears to shift gears. The study suggests that total daily energy expenditure (which includes basal metabolic rate, thermic effect of food, and activity) remains steady for a long period, implying that the weight gain some experience in their 40s or 50s may have more to do with gradual lifestyle changes rather than an inevitable metabolic nosedive. [1]

Figure A. This graph illustrates Total Energy Expenditure (TEE), which represents the total amount of energy burned by the body per day across different age groups. Notably, TEE increases exponentially during youth, stabilizes through adulthood until age 60, and declines gradually. [1]

Decline Beyond Lean Mass Alone

A complementary review, "Metabolic Changes in Aging Humans: Current Evidence and Therapeutic Strategies" by Palmer and Jensen, provides deeper insight into why resting metabolism starts slipping after 60. They note that muscle loss (sarcopenia) is only part of the story. Even when studies account for changes in muscle and fat mass, older adults display a small but consistent drop in resting metabolic rate—about four fewer calories per year once you cross into older adulthood. Over decades, that adds up. The underlying mechanisms include shrinkage and decreased efficiency of metabolically active organs such as the liver, brain, and kidneys, as well as potential mitochondrial changes and shifts in hormone balance. Chronic, low-grade inflammation also appears to dampen the body’s energy use at the cellular level. [2]

Thus, older adults don’t only burn fewer calories because they have less muscle; they also face a complex interplay of hormonal and mitochondrial alterations that further slow metabolism. This points to interventions (like targeted exercise, hormone therapies, or anti-inflammatory diets) aimed at preserving muscle and maintaining organ and mitochondrial function. [2]

Given these data, the oft-repeated lament that “your metabolism tanks in your 30s” doesn’t align well with what long-term research shows. Instead, your metabolic rate is relatively stable from your early 20s through your 50s after adjusting for body composition. Many people gain weight in their 40s or 50s. Still, the evidence suggests that declining activity levels, changing diets, and other lifestyle factors are more to blame than a sudden collapse in metabolic rate. Hormonal shifts (e.g., during menopause) certainly affect how and where the body stores fat, but they do not uniformly reduce resting metabolism as sharply as traditionally believed.

Measuring and Monitoring Metabolic Rate

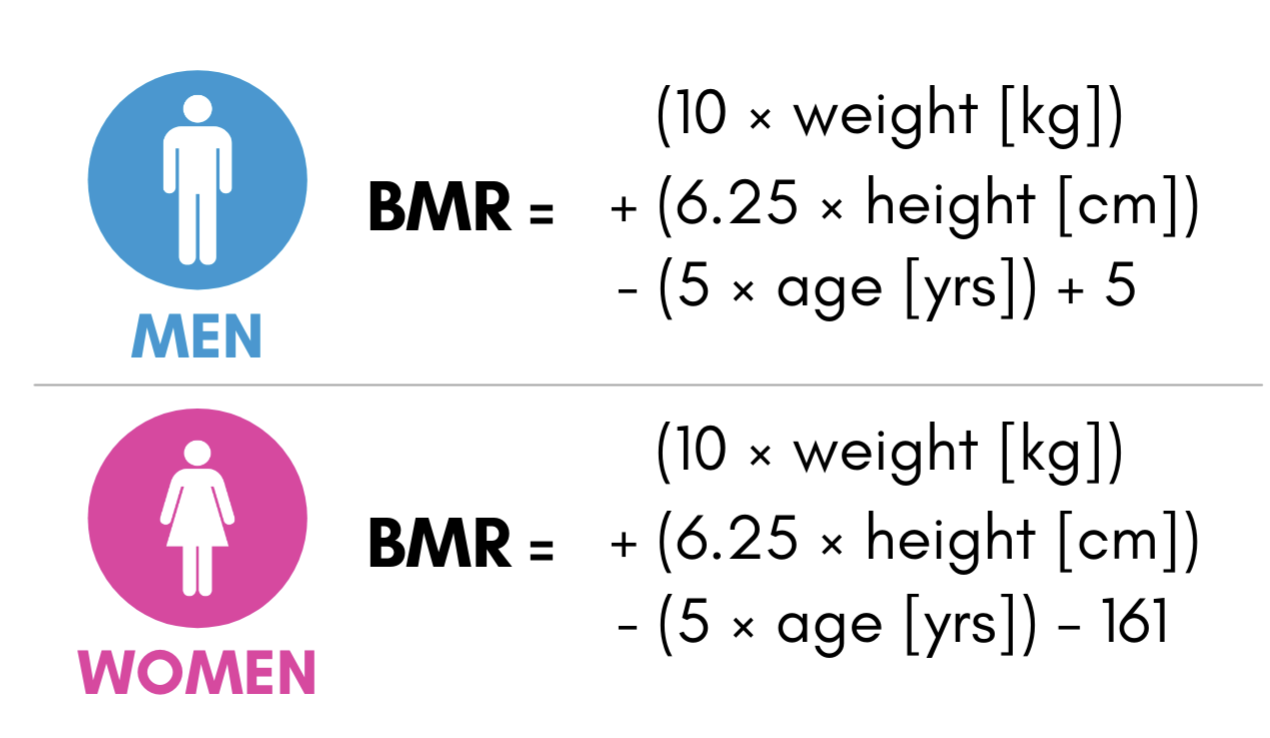

Equations such as Harris-Benedict and Mifflin-St Jeor provide an empirical approach to estimating daily energy needs based on demographic and anthropometric variables, including age, sex, height, and weight. These models approximate Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR)—the minimum energy required to sustain essential physiological functions such as cardiac activity, respiration, thermoregulation, and cellular maintenance.

While these formulas offer practical estimates, they do not account for individual variations in body composition, metabolic efficiency, or hormonal influences. For greater precision, indirect calorimetry can be employed in clinical settings, analyzing oxygen consumption (VO₂) and carbon dioxide production (VCO₂) to determine metabolic rate based on substrate oxidation.

At the highest level of accuracy, the doubly labeled water (DLW) technique serves as the gold standard in metabolic research. By tracking the turnover rates of deuterium (²H) and oxygen-18 (¹⁸O) in body fluids, DLW enables precise measurement of Total Energy Expenditure (TEE) over several days. However, its cost and logistical demands make it impractical for routine use outside of academic and clinical studies. [2]

Figure B. This image presents the Mifflin-St Jeor Equation, a widely used model for estimating Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR)—the number of calories the body requires at rest to sustain basic physiological functions such as breathing, circulation, and cellular repair. The equation calculates BMR separately for men and women, incorporating variables such as age, weight, height, and sex to provide individualized metabolic estimates. [2]

Muscle Mass and Activity Levels as Metabolic Fuel

Skeletal muscle often gets dubbed the body's metabolic powerhouse, and for good reason: pound for pound, it burns significantly more calories at rest than fat tissue. By contrast, though crucial for energy storage and hormone signaling, adipose tissue is far less energetically demanding. As a result, even modest shifts in the balance between muscle and fat can noticeably impact your total daily calorie burn.

Research consistently pinpoints lean mass (particularly skeletal muscle) as the strongest resting metabolic rate (RMR) predictor. This remains true across various ages, sexes, and body sizes. Aging typically brings about a slow but steady decline in muscle, known as sarcopenia, beginning around midlife and accelerating after 60. Part of this is fueled by hormonal changes—such as dips in testosterone, growth hormone, or estrogen—and part by a more sedentary lifestyle. When muscles aren’t regularly challenged, the body concludes that maintaining them simply isn’t worth the metabolic “overhead.” [2]

Over time, losing muscle means the body requires fewer calories to stay alive. If daily food intake remains the same while RMR trends downward, that energy surplus can be shuttled into body fat. This vicious cycle—less muscle, more fat, lower energy expenditure—can lead to creeping weight gain and diminished metabolic health. Indeed, the synergy between sarcopenia and rising fat mass (sometimes termed “sarcopenic obesity”) is associated with elevated risk for cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes.

The Role of Exercise and Protein: Evidence From a 2022 Trial

Fortunately, muscle loss can be slowed—or even partly reversed—through targeted interventions. A compelling 2022 study published in Physiological Reports explored how resistance training (RE) and a high-protein diet (via whey protein supplementation) influenced energy expenditure and body composition in healthy older men (average age: ~67 years). Over 12 weeks, participants trained two days a week, doing upper- and lower-body exercises (e.g., leg and chest presses). They also followed either a whey protein–enriched diet (roughly 1.6 g of protein per kilogram of body weight per day, around 25% of total calories) or a control diet with similar calories but less protein. [3]

Men in the resistance-training group (with or without extra protein) gained around 1.0 kg of fat-free mass. They boosted their resting metabolic rate by about 36 kcal/day relative to a non-exercising group. While 36 kcal might sound modest, small daily differences accumulate over months and years, and higher muscle mass also confers better insulin sensitivity and overall metabolic health. [3]

In a notable twist, the high-protein diet itself (even without exercise) resulted in reduced fat mass. When combined with resistance training, the protein supplementation led to a more pronounced drop in body fat—suggesting that preserving or slightly expanding muscle and optimizing macronutrient intake can help older adults better manage their weight. [3]

The study also detected a drop in daily physical activity among some participants who exercised, hinting that older adults might unconsciously rest more or move less in their free time to “compensate” for formal workouts. Over the longer term, however, the gains in muscle, RMR, and strength could outweigh this short-term decrease in incidental activity, especially if participants gradually adopt a lifestyle that reinforces staying active all day, not just at the gym. [3]

This points to a simple truth: muscle mass is essential for staying metabolically healthy as we age. By building or maintaining muscle, you increase your resting metabolic rate, helping to ward off gradual weight gain. Resistance training is the most effective way to challenge and preserve muscle tissue. Even when done twice a week, as shown in the 2022 Physiological Reports study, it can help older adults add lean mass and nudge their metabolic rate upward. For those in their 60s or beyond, a well-designed strength routine ensures that each muscle group is stimulated enough to promote growth or at least stave off loss. [3]

Protein intake is another indispensable piece of the puzzle. Aging muscle can become “resistant” to lower doses of protein, so aiming for 1.2–1.6 grams per kilogram of body weight per day can tip the balance in favor of muscle maintenance. In the Griffen et al. trial, simply adding whey protein supplementation not only helped participants hold onto muscle but also lowered their body fat. Consistency seems to be key here: brief interventions already bring measurable changes, and sustained, long-term adherence multiplies those gains. [3]

Tracking Muscle Mass and Metabolic Shifts

To see how effectively you’re maintaining or building muscle, methods like DEXA (dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry) scans offer a detailed look at lean tissue versus fat mass. This imaging-based approach is widely considered one of the best available for dissecting changes in body composition over time. Certain lab markers can also provide indirect clues. For instance, creatinine and cystatin C, which are commonly used to assess kidney function, may hint at muscle status because healthy muscle tissue contributes to creatinine production. If either marker changes without a clear kidney-related cause, it may reflect broader shifts in muscle mass and overall metabolism.

Metabolic Flexibility, Mitochondria, and Aging: Insights from Older Active Women

Mitochondria—the dynamic power plants of our cells—are central to how well we generate energy and adapt to different fuel sources (carbohydrates vs. fats). These cellular engines can become less effective with age, reducing the body’s ability to efficiently harness fats and carbohydrates for fuel. This phenomenon is sometimes labeled “metabolic inflexibility.”

Metabolic flexibility refers to how easily and efficiently our bodies switch between different fuel sources—most importantly, fats and carbohydrates—depending on our needs. For instance, during moderate-intensity exercise, an individual with high metabolic flexibility will smoothly transition to burning more fat when carbohydrate stores dip. This flexibility is crucial because relying too heavily on one single fuel (especially carbohydrates) can lead to various metabolic issues over time, such as insulin resistance and fatigue. In practical terms, a person with robust metabolic flexibility often experiences steadier energy levels and better exercise endurance.

One common method of measuring metabolic flexibility involves observing “fuel usage” during exercise. By analyzing the gases a person exhales, researchers can determine whether they are burning a higher proportion of fats or carbohydrates. The greater the capacity for fat oxidation—meaning the ability to tap into fat stores—the higher one’s metabolic flexibility tends to be. The opposite scenario, in which the body struggles to use fats, is frequently called “metabolic inflexibility.”

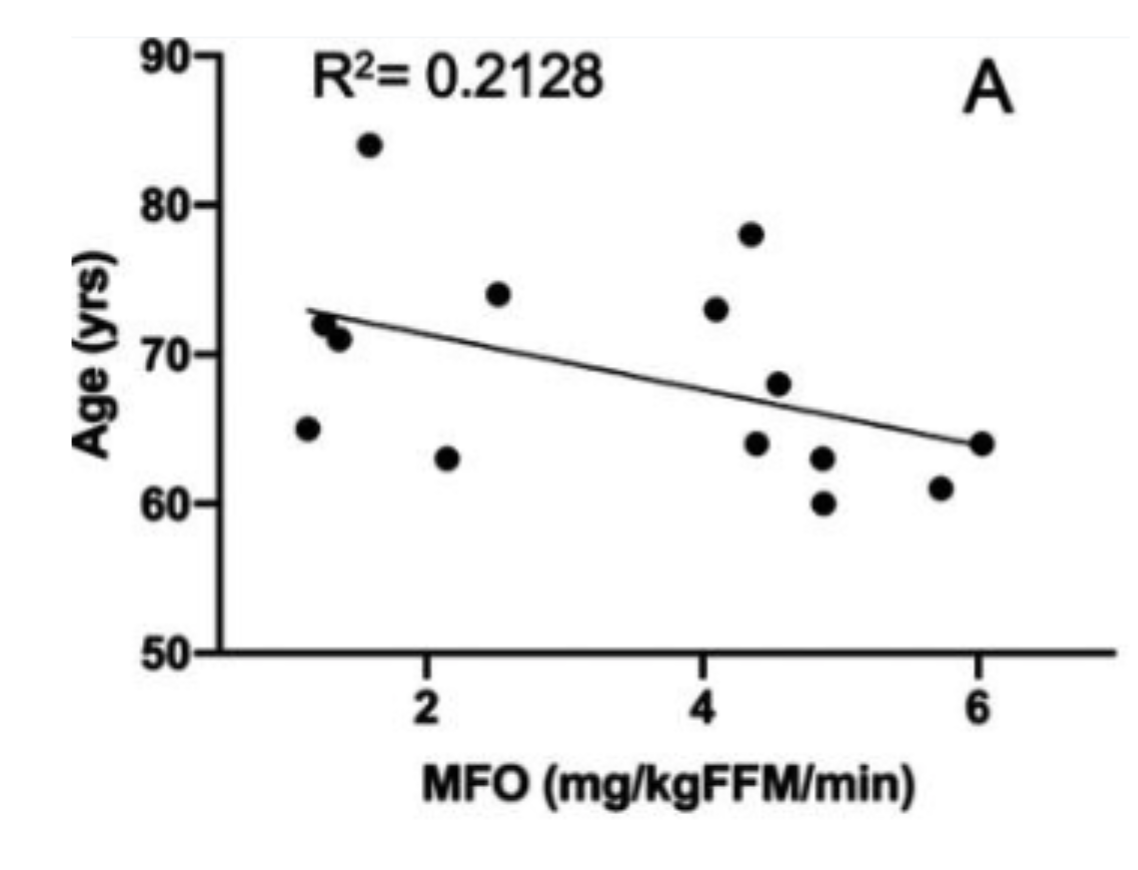

Although many older adults experience some decline in mitochondrial function, it remains possible to slow or mitigate these changes through an active lifestyle. A recent pilot study examined a group of women over 60 who were already physically active, mostly through Nordic walking and regular daily movement (Monferrer-Marín et al., 2022). Researchers had these women complete incremental cycling tests, starting at low power outputs and gradually increasing them every few minutes. They monitored several factors throughout the test, including how efficiently the participants burned fat (fat oxidation or FATox) and carbohydrates (CHOox). [4]

Despite regular physical activity, the results showed that these older women displayed strikingly low maximal fat oxidation (often referred to as MFO). Their MFO was roughly half of what one might see in younger or middle-aged populations. This diminished fat-burning capacity became evident at relatively modest exercise intensities—essentially, their muscle cells began to favor carbohydrates more quickly. Meanwhile, total energy expenditure was lower than expected, suggesting these older muscles couldn’t generate as much energy (in calories per minute) when pushed. [4]

Figure C. This graph plots maximal fat oxidation (MFO) along the x-axis against age on the y-axis. MFO refers to the highest rate at which an individual’s body can burn fat during exercise, serving as a key indicator of metabolic flexibility. In this study, younger participants (closer to 60) display higher MFO values, implying more robust fat-burning capacity, while older individuals, though very physically active, exhibit lower MFO, signaling a notable decline in the ability to utilize fat as a primary fuel source. [4]

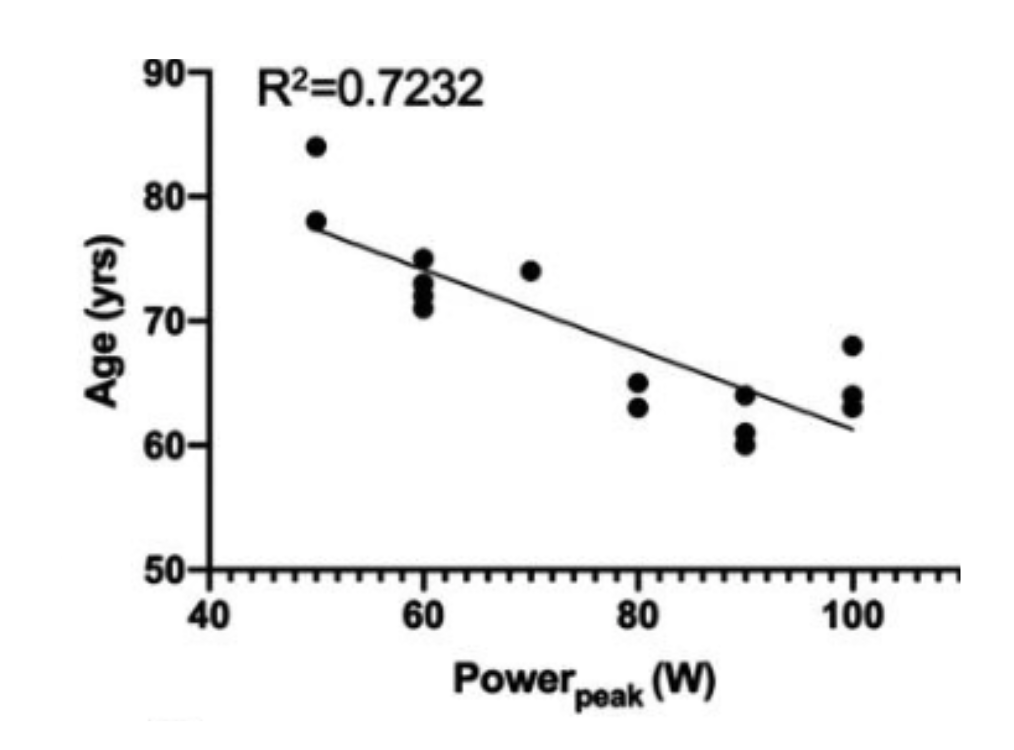

Interestingly, muscle power—essentially, how forcefully and quickly their muscles could contract—emerged as a protective factor. Women who could produce greater power during cycling tended to oxidize more fat, implying that exercises focused on strength or power could help older adults maintain better overall metabolic flexibility. The study also found that blood lactate, a byproduct of carbohydrate metabolism, rose normally, which means carbohydrate-burning pathways were still intact. The real shortfall lay in the ability to tap into fat reserves. [4]

Figure D. This graph compares peak power output on the x-axis with age on the y-axis. The term “peak power” describes the maximum wattage or force an individual can generate, reflecting muscle strength and neuromuscular efficiency. Here, younger subjects produce higher peak power. In contrast, although very physically active, older participants show a clear decline, underscoring how advancing age can erode muscular performance even in an active population. [4]

A major reason behind this drop in fat oxidation is a decline in the quality and number of mitochondria inside muscle cells. Over time, mitochondria may suffer structural damage—particularly to a specific internal membrane where the electron transport chain (ETC) resides. The ETC is a series of protein complexes that pass electrons along, much like an assembly line, to produce ATP. If these complexes or the membrane itself is damaged, the cell’s ability to churn out energy efficiently falters. As a result, the muscle shifts to burning carbohydrates at lower exercise intensities, and overall energy production is blunted. [4]

This phenomenon is sometimes referred to as a loss of mitochondrial density and enzyme function. Weaker mitochondria translate into a lower capacity to handle aerobic (oxygen-dependent) metabolism, so the body resorts to carbohydrates earlier than normal. Although this shift isn’t necessarily harmful in small doses, it does mean that an older adult might tire more quickly and rely on carbohydrates in situations where a younger person would still be burning.

Mitochondrial Interventions and Ways to Measure Progress

Evaluating the health of our mitochondria is a key first step in designing interventions that protect or restore their function. Clinicians and researchers often rely on specific lab markers to spot potential weaknesses in energy production. For instance, lactic acid (lactate) levels can rise prematurely during exercise if muscle cells are forced to burn carbohydrates instead of fat, suggesting that mitochondria may not meet aerobic metabolism's demands. Additionally, fasting insulin and glucose values provide insight into how well the body manages blood sugar since metabolic inflexibility (often tied to poor mitochondrial function) can show up in elevated insulin resistance. In organic acid tests (OAT), certain urine metabolites flag inefficiencies in the biochemical pathways that govern mitochondrial energy production, while measuring coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) helps determine whether key components of the electron transport chain are in short supply. [4]

Tracking these markers enables clinicians to shape personalized strategies for enhancing mitochondrial health. Approaches range from dietary adjustments—such as ensuring adequate protein intake and a balanced macronutrient profile—to structured exercise plans targeting mitochondrial capacity. In some instances, experimental therapies like elamipretide (an agent that stabilizes the inner mitochondrial membrane) may be considered for individuals who qualify for clinical trials or specialized treatment protocols. [4]

Beyond these medical and biochemical measures, a substantial body of research underscores that many age-related declines in mitochondrial function are neither permanent nor inevitable. Both endurance training and strength/power training have consistently shown to be beneficial. Endurance activities like brisk walking, jogging, or moderate cycling appear to help preserve mitochondrial volume and enzyme activity, as observed in studies of older endurance athletes with higher-than-average citrate synthase levels—a key indicator of mitochondrial density. Meanwhile, power-focused routines that emphasize resistance or explosive movements can significantly boost muscle output. In a pilot study of active older women, those who achieved greater power during cycling also demonstrated superior fat-burning capacity, suggesting that training for both endurance and power may be especially important for maintaining metabolic flexibility. By combining targeted lab assessments with a tailored exercise regimen and possible medical interventions, individuals can work toward preserving robust mitochondrial function and improving overall energy metabolism well into older age. [4]

Hormonal Changes Impact Metabolism

Aging is accompanied by progressive alterations in endocrine function, which exert significant effects on body composition, energy homeostasis, and disease susceptibility. Declining levels of sex hormones, including testosterone and estrogen, contribute to changes in muscle mass, fat distribution, and insulin sensitivity, all of which influence metabolic efficiency. Understanding the mechanistic links between hormonal fluctuations and metabolic regulation is essential for developing targeted interventions aimed at preserving physiological function and mitigating age-related metabolic decline.

Testosterone in Men

For men, testosterone levels typically peak in early adulthood and gradually decline with each passing decade. This gradual decline, often referred to as “andropause,” can be subtle but may manifest as increased fat mass—especially in the visceral region—along with decreased muscle mass, lower bone density, and a reduced sense of well-being. Notably, emerging research suggests that this decline in testosterone is linked to age-related mitochondrial dysfunction in the testes, which may impair Leydig cell function and reduce androgen production.

Clinical trials focusing on older men with low testosterone (sometimes called “late-onset hypogonadism”) provide strong evidence that testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) can modestly improve body composition. Patients may see modest drops in total body fat and some gains in lean muscle mass, coupled with potential improvements in insulin sensitivity. [5]

A pivotal example is the “T4DM trial” (Testosterone for the Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in High-Risk Men). In this study, men with obesity and prediabetes were assigned to a lifestyle intervention or the same intervention plus testosterone therapy. Results showed that men receiving testosterone had fewer progressions to type 2 diabetes, indicating that restoring testosterone in this population could positively influence glucose handling and metabolic regulation. [5]

However, it is essential to note that testosterone therapy is not a blanket solution. Risks can include fluid retention, sleep apnea exacerbation, and concerns about prostate health. Additionally, given the link between mitochondrial function and testosterone production, interventions targeting mitochondrial health—such as exercise-induced mitochondrial biogenesis or Urolithin A—may also play a role in preserving testosterone output. Consequently, clinicians typically conduct thorough evaluations before prescribing TRT, including assessing prostate-specific antigen (PSA), hematocrit, and cardiovascular status.

Estrogen in Women

In women, estrogen levels drop significantly during the menopausal transition. This change has often been cited as a major driver of altered body composition and metabolism. However, a 2023 study revealed that while postmenopausal women commonly experience shifts such as increased abdominal fat, the overall decline in resting metabolic rate (RMR) during midlife appears more strongly linked to chronological aging than to menopause itself. These findings suggest that low estrogen may not always be the root cause of metabolic slowdown at this life stage, underscoring the importance of evaluating other factors such as thyroid function, muscle mass, physical activity levels, and dietary habits. [6]

Although estrogen may not solely dictate changes in RMR, it still influences fat distribution—with lower estrogen frequently associated with a shift toward central (visceral) fat—and can affect appetite regulation. Some postmenopausal women also notice increased insulin resistance. For those experiencing pronounced menopausal symptoms or adverse changes in body composition, hormone replacement therapy (HRT) with estrogen (sometimes combined with progesterone) can be beneficial. However, any form of HRT must be considered carefully in the context of individual risk profiles, including factors like breast cancer and cardiovascular history. [6]

Addressing Hormonal Imbalances

Improving hormonal balance and mitigating age-related metabolic shifts often begins with lifestyle modifications that encompass exercise, nutrition, and stress management. To start, resistance training—including weightlifting, resistance bands, or bodyweight exercises—can be particularly advantageous. Such workouts help sustain or even boost resting metabolic rate (RMR) by promoting muscle maintenance and stimulating the GH/IGF-1 axis. In men, resistance training has been associated with healthier testosterone levels, while in women, it helps counteract the muscle loss that often accompanies midlife hormonal transitions. [5, 6]

Engaging in endurance or cardiovascular activity adds another layer of protection against unwanted metabolic changes. Brisk walking, jogging, cycling, or swimming boosts insulin sensitivity and encourages a more favorable distribution of body fat. These benefits are relevant for both men and women but may be especially important during midlife when shifts in sex hormones can accelerate fat gain and reduce muscle mass. By combining strength training and aerobic workouts, individuals often see synergistic effects on muscle tone, fat reduction, and metabolic rate—key factors in navigating hormonal changes effectively. [5, 6]

Beyond these lifestyle foundations, some individuals may benefit from more direct hormone replacement or medical interventions. For women experiencing significant menopausal symptoms or unusual weight gain, estrogen or combined hormone replacement can limit central fat accumulation and help stabilize mood and energy levels. Yet since low estrogen is not always the sole cause of metabolic shifts, it is crucial to investigate alternative explanations, including reduced physical activity, suboptimal thyroid function, or diminished lean mass. Tailoring hormone therapy to address each person’s unique medical history is essential for balancing the potential benefits against possible risks, such as increased breast cancer or cardiovascular risk. [6]

Inflammation & Insulin Resistance Undermining Metabolic Health

A growing consensus in aging and obesity research pinpoints chronic low-grade inflammation, often termed “inflammaging,” as a significant driver of metabolic decline. Under normal conditions, the body’s immune response is finely tuned to eliminate threats such as pathogens or tissue damage, then subside. However, in individuals who are older or carry excess weight, the immune system can become overactive at a low level and fail to return to equilibrium. This persistent inflammatory state is fueled by immune cells and fat cells alike, with both releasing high levels of signaling molecules called cytokines—particularly TNF-α (tumor necrosis factor-alpha) and IL-6 (interleukin-6)—as well as increased amounts of C-reactive protein (CRP).

What makes these molecules so detrimental to metabolic health is their capacity to disrupt insulin signaling pathways. Under normal conditions, insulin binds to receptors on muscle and liver cells, prompting them to absorb glucose from the bloodstream. When pro-inflammatory cytokines are abundant, they interfere with multiple steps in this signaling process. For example, TNF-α can promote the phosphorylation of proteins in a way that shuts down glucose uptake, forcing insulin levels to spike in an attempt to clear blood sugar. Over time, this scenario results in insulin resistance, wherein cells become progressively less responsive to insulin, blood glucose levels remain high, and the pancreas strains to produce more and more insulin.

A body of large-cohort studies supports this connection. One project used the Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index (SII) to categorize participants according to their inflammatory status and found that those in the highest tertile of inflammation had both significantly higher fasting insulin and higher HOMA-IR (homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance) scores than those in the lowest tertile. Even after accounting for lifestyle variables, body weight, and comorbidities, inflammation-rich participants showed about a 35% greater risk of insulin resistance. Such figures suggest that inflammation does more than just accompany metabolic disorders—it may also help drive them. [7]

Yet, inflammation and insulin resistance form a vicious cycle. As cells become more resistant to insulin, blood glucose rises, prompting the pancreas to release additional insulin. Excess glucose frequently converts to fat, increasing adipose tissue stores that can act like an endocrine organ, secreting more pro-inflammatory factors. This means that once systemic inflammation and insulin resistance become entrenched, each can worsen the other, creating a complex web of metabolic dysfunction that is challenging to unravel without targeted intervention. [7]

Identifying and Managing Inflammation to Improve Insulin Sensitivity

Determining whether chronic inflammation undermines metabolic health often starts with targeted laboratory assessments. High-sensitivity CRP (hs-CRP), for instance, detects subtle elevations in the inflammatory protein CRP, making it a key early-warning signal for cardiometabolic risk. Elevated HbA1c can hint at longer-term difficulties controlling blood sugar, which inflammation may exacerbate. Measuring fasting insulin and fasting glucose can uncover hyperinsulinemia—an early hallmark of insulin resistance—before overt changes show up on an HbA1c test. Meanwhile, adiponectin and leptin levels can offer additional clues about adipose tissue’s contribution to inflammation: low adiponectin correlates with reduced insulin sensitivity. In contrast, leptin resistance can trigger overeating and systemic metabolic stress. [7]

Once markers indicate that inflammation plays a significant role in metabolic dysfunction, addressing the issue typically involves a multi-pronged strategy. Weight loss and dietary adjustments are often the first line of defense. Reducing overall adiposity lowers the production of inflammatory signals from fat cells, and research on caloric restriction or intermittent fasting (IF)—such as alternate-day fasting or time-restricted feeding—shows noteworthy improvements in insulin sensitivity alongside decreases in inflammatory markers. In one eight-week alternate-day fasting study, obese adults not only lost weight but did so without experiencing spikes in stress-related cytokines. Beyond simple calorie cuts, emphasizing anti-inflammatory foods (e.g., rich in omega-3 fatty acids, antioxidants, and fiber) can help tamp down chronic inflammation and improve glycemic control, as observed in Mediterranean-style diets. [8]

Pairing nutritional measures with regular physical activity further intensifies the anti-inflammatory effect. Aerobic exercise like walking or swimming helps burn visceral (or “active”) fat, which is particularly prone to releasing inflammatory mediators. Resistance exercises, on the other hand, preserve or enhance lean muscle mass—an important tissue for insulin uptake—while also boosting resting metabolism. Over time, these combined benefits ease the body’s inflammatory burden and improve insulin-mediated glucose disposal. [8]

When lifestyle interventions are insufficient, targeted pharmacologic approaches may be warranted. The 2017 CANTOS trial demonstrated that inhibiting IL-1β, a potent pro-inflammatory cytokine, substantially reduced CRP levels and the incidence of new-onset diabetes. Among emerging interventions, rapamycin has garnered interest for possibly modulating inflammatory pathways in ways that could improve metabolic health. Current evidence on rapamycin is still evolving, with some animal models indicating beneficial effects on insulin resistance and aging-related inflammation. [7]

Altogether, identifying inflammation through precise lab markers and then deploying an integrative approach—merging dietary changes, regular exercise, and, if necessary, targeted pharmacological therapies—can break the destructive loop between chronic inflammation and impaired insulin signaling. By reducing cytokine production and improving the body’s capacity to handle glucose, these strategies offer a path to more resilient metabolic health.

Conclusion: What Can You Do to Keep Your Metabolism High?

Although metabolism does tend to shift with age, decades of research demonstrate that such changes are not set in stone. By regularly checking the key biomarkers that reveal your muscle mass, mitochondrial health, thyroid function, inflammatory status, and glucose regulation, you can detect subtle signs of slowdown and respond with precisely targeted interventions. Below are several evidence-based approaches that, when integrated thoughtfully, can preserve—and even enhance—your metabolic vitality:

1. Identify Root Causes Through Key Biomarkers: Before adjusting your diet or adding new therapies, it’s essential to determine why your metabolism may be faltering. Tracking leptin, hs-CRP, fasting insulin, fasting glucose, and other hormone levels can reveal whether your primary issues stem from chronic inflammation, insulin resistance, or low muscle mass. By clarifying which factors are at play—excess adiposity, underactive thyroid, or poor glucose regulation—you can tailor your approach and tackle the problem at its source rather than merely treating superficial symptoms.

2. Build and Maintain Muscle Through Resistance Training: Muscle acts as your body’s metabolic powerhouse, burning energy even at rest. Resistance exercises—from classic weightlifting to bodyweight circuits—help stave off the age-related decline in lean mass that often drags metabolic rates downward. To track your progress, you can measure creatinine and CK (creatine kinase) levels or undergo a DEXA scan to assess gains (or losses) in muscle. The stronger and more muscular you become, the more resilient your basal metabolism remains.

3. Adopt a High-Protein Diet: Preserving and building muscle also hinges on adequate protein intake, which supports repair and growth while curbing the loss of lean tissue. Aiming for approximately 1.2 to 1.6 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day can sustain muscle health—especially when combined with regular training. Monitoring BUN (Blood Urea Nitrogen) and occasionally conducting amino acid panels helps confirm whether you’re meeting your protein needs without placing undue stress on your system.

4. For those facing elevated blood sugar or insulin resistance, certain medications can offer a valuable boost. Acarbose slows carbohydrate digestion, cutting down on sharp post-meal glucose spikes, while SGLT-2 inhibitors work to excrete excess glucose through the urine. Both approaches can enhance insulin sensitivity and unburden an overworked pancreas. Keeping an eye on fasting insulin, fasting glucose, HbA1c, and lipid profiles will help you determine how effectively these interventions are modulating your metabolic pathways.

5. Experiment with Cold Exposure, Heat Therapy, and Intermittent Fasting: Emerging science points to cold exposure (e.g., ice baths) and heat therapy (e.g., saunas) as potential ways to support mitochondrial function and quell low-grade inflammation. Intermittent fasting or time-restricted eating can help regulate insulin and leptin—a hormone crucial for appetite control and fat storage. Monitoring changes in leptin, fasting glucose, and hs-CRP can clarify how your body responds to these modalities, guiding you to refine or adopt additional interventions.

Maintaining a high-functioning metabolism in later life isn’t about blindly following popular diet trends or exercise fads. Instead, it requires a personalized approach built on precise data and deliberate strategies. By pinning down the root causes—whether it’s chronic inflammation, insulin resistance, or inadequate muscle mass—and combining strength-building activities, thoughtful dietary patterns, and (if necessary) medical therapies, you can preserve metabolic resilience, ultimately leading to sustained energy, better weight management, and improved overall health.

- Pontzer H, Yamada Y, Sagayama H, et al.; IAEA DLW Database Consortium. Daily energy expenditure through the human life course. Science. 2021 Aug 13;373(6556):808-812. doi: 10.1126/science.abe5017. PMID: 34385400; PMCID: PMC8370708.

- Palmer AK, Jensen MD. Metabolic changes in aging humans: current evidence and therapeutic strategies. J Clin Invest. 2022 Aug 15;132(16):e158451. doi: 10.1172/JCI158451.

- Griffen C, Renshaw D, Duncan M, et al. Changes in 24-h energy expenditure, substrate oxidation, and body composition following resistance exercise and a high-protein diet in older men. Physiol Rep. 2022 Jun;10(11):e15268. doi: 10.14814/phy2.15268. PMID: 37815091; PMCID: PMC9332127.

- Monferrer-Marín J, Roldán A, Monteagudo P, et al. Impact of ageing on female metabolic flexibility: a cross-sectional pilot study. Sports Med Open. 2022 Jul 30;8(1):97. doi: 10.1186/s40798-022-00487-y. PMID: 35907092; PMCID: PMC9339052.

- Bhasin S. Testosterone replacement in aging men: an evidence-based patient-centric perspective. J Clin Invest. 2021 Feb 15;131(4):e146607. doi: 10.1172/JCI146607. PMID: 33586676; PMCID: PMC7880314.

- Karppinen JE, Wiklund P, Ihalainen JK, et al. Age but not menopausal status is linked to lower resting energy expenditure. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023 Oct 18;108(11):2789-2797. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgad321. PMID: 37265230; PMCID: PMC10584005.

- Guo H, Wan C, Zhu J, et al. Association of systemic immune-inflammation index with insulin resistance and prediabetes: a cross-sectional study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2024 Jun 5;15:1377792. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2024.1377792. PMID: 38904046; PMCID: PMC11188308.

- Silva AI, Direito M, Pinto-Ribeiro F, et al. Effects of intermittent fasting on metabolic homeostasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2023 May 26;12(11):3699. doi: 10.3390/jcm12113699. PMID: 37297894; PMCID: PMC10253889.