Cell senescence, Rapamycin and Hyperfunction Theory of Aging

Overview

A hallmark of cellular senescence is proliferation-like activity of growth-promoting pathways (such as mTOR and MAPK) in non-proliferating cells. It is growth without a goal or purpose and when the cell cycle is arrested, these pathways convert arrest to senescence, in a process called geroconversion, thus rendering cells hypertrophic, beta-Gal-positive and hyperfunctional. Please note that hypertrophic is the enlargement of an organ or tissue from the increase in size of its cells, beta-Gal-positive is a marker for cell senescence due to its role in catalyzing the hydrolysis of β-galactosides into monosaccharides which only occurs in senescent cells, and the hyperfunctional state is responsible for many dysfunctions that lead to and produce many age-related diseases . Additionally, the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) is one of the numerous hyperfunctions. Once again, geroconversion is figuratively a continuation of growth in non-proliferating cells. Rapamycin, a reversible inhibitor of growth, slows down mTOR-driven geroconversion. Developed two decades ago, this model had accurately predicted that rapamycin must extend the life span of animals. However, the notion that senescent cells directly cause organismal aging is oversimplified. Senescent cells contribute to organismal aging but are not strictly required. Cell senescence and organismal aging can be linked indirectly via the same underlying cause, namely hyperfunctional signaling pathways such as mTOR. Just to be clear, when you read words such as mTOR or PI3K know that these are the names of genes, their corresponding pathways, and their genetic products.

Preface

The activity of mitogen-activated and growth-promoting pathways such as PI3K/mTOR and ERK/MAPK is unremarkable in senescent cells compared to proliferating cells. But this seemingly “unremarkable” lack of difference is remarkable in and of itself: proliferation-like activity of growth-promoting pathways in non-proliferating cells [1]. But why should we compare apples and oranges? The most relevant counterpart to senescence is quiescence: cell growth cycles are arrested but are not senescent which is like most cells in an organism. In such a comparison, a difference emerges: the activity of growth-promoting pathways, such as mTOR and MAPK pathways, is high in senescent cells, as if these senescent cells proliferate. However, they do not.

There are many paradoxes in the field of cell senescence. For example, as we will discuss later, hyperfunctional mitogenic signaling involving MEK/ERK/MAPK pathways can cause senescence instead of accelerated proliferation [2–7]. In addition, forced activation of the cell cycle in quiescent cells may lead to apoptosis, instead of proliferation [7].

Seemingly paradoxically, all known anti-aging interventions in animals from nutrient restriction to rapamycin can slow down cell proliferation.

How and why does rapamycin inhibit cell proliferation but maintains proliferative potential in the arrested cells?

Also, discussed here is the notion that senescent cells contribute to age-related diseases, but are not required for the onset or continuation of these age-related diseases. In the organism, senescent cells are a subset of gerogenic cells, which do not look like senescent cells. Finally, this article attempts to link cell senescence and organismal aging.

Conventional view on cell senescence is inadequate

For most scientists, the term “cellular senescence” means irreversible cell cycle arrest or, more precisely, permanent loss of proliferative potential. For the rest of us, cellular senescence is when cells stop multiplying but do not die off when they should and instead continue “growing.” Furthermore, This is known as the Golden Marker of cell senescence. However, all attempts to link cell cycle arrest to organismal aging have not been successful. The oldest people and animals do not die from bone marrow failure or intestinal atrophy due to cessation of cell proliferation. In contrast, aging is associated with hyper-proliferative conditions such as cancer and leukemia, organ hypertrophy (e.g. prostate and heart hypertrophy), atherosclerotic plaques, tissue fibrosis, obesity, and others. Please note that hyper-proliferation is an abnormally high rate of proliferation of cells via rapid cell division.

For example, myocardial infarction, a common cause of death in humans, is caused by neither cell cycle arrest nor DNA damage. It is cell growth and excessive functions (hyperfunction) that, via multiple steps, lead to atherosclerosis, hypertension, vasoconstriction and thrombosis, culminating in myocardial infarction.

Increasingly, despite the definition, the link between cell senescence and organismal aging becomes viewed via SASP or hyper-inflammatory phenotype of senescent cells [8–18]. This is a step in the right direction, but still insufficient. SASP is a typical hyper-function with secretion being a normal function of many cell types, but it is not the only one. Most functions are tissue-specific. For example, functions of blood platelets are adhesion and aggregation, for macrophages – phagocytosis, including phagocytosis of oxidized LDL. Hyperfunction of arterial smooth muscle cells (SMC) results in cell hypertrophy, vessel stiffness, and vasoconstriction, which all contribute to hypertension a form of systemic hyperfunction and atherosclerosis (see Ref. [19])

Also to be discussed is the seemingly paradoxical notion that despite permanent loss of proliferative potential, senescence is not a form of arrest, it is a form of growth [25]. Cell senescence cannot be understood without the concept of geroconversion – a conversion from non-senescence to senescence or a continuation of growth, when actual growth is completed [1,25]. Let us start from the beginning.

Proliferation, quiescence and senescence in cell culture

Proliferation:

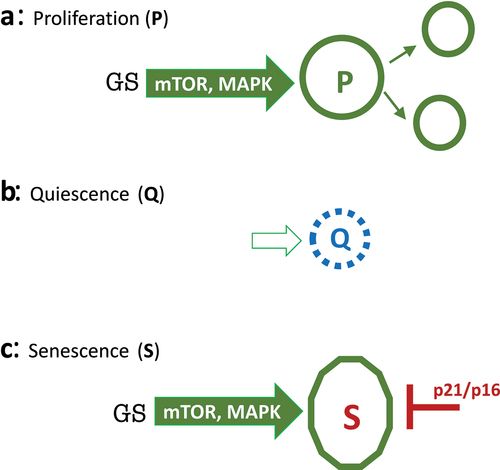

In cell culture, growth factors (GF) and nutrients stimulate growth-promoting pathways such as MEK/MAPK and PI3K/mTOR (Figure 1a). These pathways stimulate cellular mass growth and induce cyclin D1, which itself initiates cell cycle progression. As such Mass growth is balanced by cell division [1].

Figure 1. Representation of proliferation, quiescence and senescence.

A: Proliferation. Growth Signaling or Growth Stimulation (GS) via growth-promoting pathways (PI3K/mTOR; ERK/MAPK) stimulates cellular mass growth and activates cell cycle. Cells progress to mitosis and divide. Thus, cellular mass growth is balanced by cell division. B: Quiescence (Q). In the absence of GS cells, mTOR and MAPK are deactivated, and the cell cycle is put on hold. Cells neither grow nor cycle. In normal cell culture, quiescence can be caused by serum/GFs withdrawal, contact inhibition, anoxia and nutrient-restriction. C: Senescence (S). When the cell cycle is blocked by p21 or p16, growth signaling drives senescence instead of proliferation.

Quiescence:

In the absence of growth stimulation, MAPK and mTOR are deactivated, cyclins are not induced, the cell cycle slows down and cells stop proliferating – a condition known as quiescence (Q) (Figure 1b). In this state, cells neither grow in size nor cycle. Quiescent cells are small and metabolic processes are downregulated. In cell culture, quiescence can be caused by withdrawal of serum, growth factors and nutrients, thus deactivating MAPK and mTOR and causing, in turn, cell cycle arrest [1]. (Note: Some cancer cells tend to die rather than become quiescent for the reason discussed in the last section.) Quiescence is reversible by growth stimulation, such as the readdition of growth factors or serum.

Contact inhibition also causes quiescence [26]. In contact-inhibited cells, MAPK and mTOR pathways are deactivated, halting both cell mass growth and cell cycle (26). Splitting contact-inhibited cells into a lower density culture re-activates MAPK and mTOR pathways and releases the cell cycle. The cells then re-start proliferation. Contact inhibition is the cessation of cellular movement, growth, and division upon contact with other cells.

Senescence:

Once again, in quiescence, cell cycle arrest is caused by the deactivation of growth-promoting (MAPK, mTOR, etc.) pathways. However, the cell cycle can be blocked directly by production of p21 and p16, which in turn can be induced by numerous stressors (Figure 1c). When the cell cycle is blocked in such a manner, mTOR and MAPK remain fully activated, driving unbalanced growth without inducing cell division and cyclins D which again promote the advancement of the cell through the cell cycle. This induction is futile, however, because the cell cycle is blocked by p21 and p16. The cell is frozen in a hypermitogenic state [1]. Cells have a large and flat morphology and are hyperactive and hyperfunctional (e.g, SA-beta-Gal staining is lysosomal hyperfunction and SASP is secretory hyperfunction).

Thus, a combination of molecular markers of senescence is as follows: p16 and p21 (markers of cell cycle block) plus phospho-S6 (a convenient marker of mTOR activity) and cyclin D1 (a marker of overstimulation (1).

Molecular Markers of Cell Senescence:

- P16

- P21

- phospho-S6

- Cyclin

Figuratively, the process of geroconversion is “twisted” growth when actual growth is completed [1,25,27]. mTOR drives geroconversion, rendering cells hypertrophic and hyperfunctional (e.g. SASP) and thus leading eventually to age-related pathologies [27–29].

The car analogy: push brake and gas at the same time

When a driver pushes the gas pedal (analogous to growth stimulation), the car drives. This is proliferation (Figure 1a). When the gas pedal is released, the car slows down and stops (Figure 1b). This is a reversible quiescence. In cell senescence, the cell cycle is blocked by powerful brakes, such as p16 and/or p21, in the presence of growth stimulation (Figure 1c). In this senescence analogy, the brakes and accelerator are pushed simultaneously. Eventually, the car will be out of order. This analogy is applicable not only to cellular senescence but also to organismal aging [30].

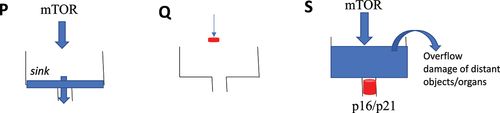

The clogged sink analogy

Senescent cells can be damaging to the organism. This is not molecular damage but organ damage and mostly to the distant organs. Consider the clogged sink analogy (Figure 2). In proliferation, the water comes into the sink and gets out. If you close the faucet, water does not come at all (quiescence) and the sink is empty, as well. However, if the sink is clogged and the faucet is still turned on (cell senescence), then the problem arises. The water overflows the sink and may damage distant objects, such as a laptop on the floor or even the floorboards themselves. Similarly, hyperfunctional cells in the arterial walls, liver, adipose tissue, and the hematopoietic system can eventually cause atherosclerosis and thrombosis, leading to a stroke, damaging the brain.

Figure 2. The clogged sink analogy for proliferation, quiescence and senescence.

P: Proliferation. Unrestricted flow of the water (blue) to the sink and out. Q: Quiescence. The faucet is closed (red). The sink is empty. S: Senescence. The faucet is opened (red), but the sink is clogged. The sink is full of water, causing outflows and damage to the distant objects (organs).

From the model of geroconversion to the hyperfunction theory

The hyperfunction theory is a translation of the rules of geroconversion to organismal aging [31].

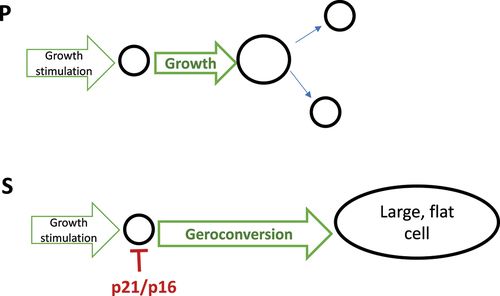

Geroconversion is the continuation of a growth program when actual growth is restricted by cell cycle arrest. Geroconversion is a quasi-program of growth (Figure 3). Organismal aging is a continuation of developmental growth, when actual growth is completed. Aging is a quasi-program of developmental growth [27,31–37].

Figure 3. Geroconversion is a form of “twisted” growth.

P: Proliferation. Cells grow in size and divide. S: Senescence. Geroconversion is a continuation of growth when the cell cycle is blocked by p21/p16.

Both geroconversion and organismal aging are driven in part by the mTOR pathway (Figure 4). Like cell senescence, organismal aging is primarily associated with hypertrophy and hyperfunction that eventually lead to diseases of aging, organ damage and secondary loss of function.

Examples of organismal hyperfunctions include:

- Hypertension

- Hyperglycemia

- Hyperlipidemia

- Hyperinsulinemia

- Hypercoagulation

- Prostate hypertrophy autoimmunity

- Osteoarthritis

- Early stages of many diseases.

Hyperfunctions eventually lead to organ and system damage and loss of functions [27]. This creates the illusion that aging is primarily functional decline. Since it is more difficult to restore function than to suppress hyperfunctions, thus rapamycin should be most effective before organ damage occurs [27].

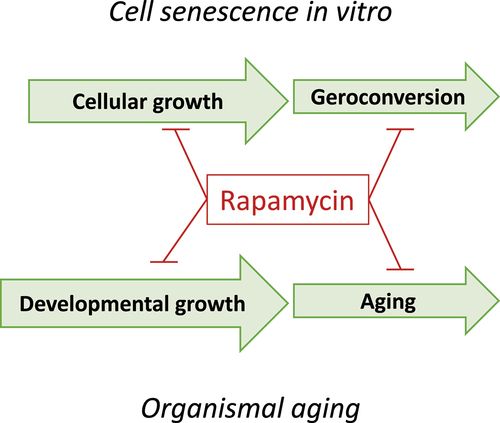

Figure 4. The analogy between cell senescence and organismal aging.

Both geroconversion and aging can be depicted as a continuation of growth. Rapamycin, gerostatic, slows down growth (cytostatic), geroconversion and aging

Oversimplified model of cellular senescence in organismal aging

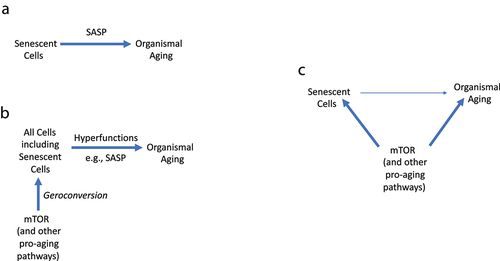

Figure 5a exemplifies a conventional and oversimplified model linking cellular senescence to organismal aging:

Figure 5. Linking cell senescence to organismal aging.

A. Oversimplified model. Cell senescence causes organismal aging (and age-related diseases) via SASP. B. Comprehensive model. Fully senescent cells contribute but are not absolutely required for aging (and age-related diseases) C.The common cause model. The link between senescence and aging is mostly indirect, by sharing the same signaling pathways that drive both geroconversion in cell culture and organismal aging (and age-related diseases). Senescent cells contribute but are not absolutely required.

However, this simple schema (Senescent cells-SASP-Aging) cannot substitute the complex pathogenesis of age-related diseases, which involves multiple cell types and different hyperfunctions. Notably, SASP is just one of the numerous cellular hyperfunctions, and its suppression may not always be sufficient for life extension. For example, glucocorticoids inhibit SASP [12]; however, glucocorticoids do not extend life span. In contrast, very high levels of glucocorticoids in untreated Cushing’s disease are associated with a poor prognosis; with the median survival being about five years [38].

From an oversimplified model to hyperfunctional model

Let us return to the example of myocardial infarction. The atherosclerotic plaque consists of hypertrophic and hyperplastic SMC, hyperfunctional macrophages (foam cells) which, cause calcification and lipid accumulation by foam cells. Hyperfunctional endothelial cells attract hyperfunctional blood platelets with a higher propensity to adhere and aggregate. Atherosclerosis, hypercoagulation, platelet overactivation, and hypertension myocardial hypertrophy all together may lead to myocardial infarction.

According to the hyperfunction theory, the sequence of events is:

- Constitutively active signaling pathways (in the absence of growth)

- geroconversion

- Hyperfunctional gerogenic cells (including a few senescent cells)

- Tissue-specific hyperfunctions (including SASP)

- Age-related diseases, whose sum is aging (

In the organism, geroconversion creates a few senescent cells but makes all cells hyperfunctional (gerogenic), causing age-related diseases – which are deadly manifestations of aging. More generally, senescent cells may contribute to organismal aging but are not required. Even this model is not sufficient to fully understand the link between cellular senescence and organismal aging.

Gerostatics

The concept of geroconversion allowed us to discover gerostatics (a subgroup of cytostatic drugs that slow down not only cell proliferation but also geroconversion). Rapamycin and other rapalogs are prototypical gerostatics. All gerostatics may induce cell cycle arrest on their own, but in the presence of p21/p16-induced cell cycle arrest, their gerostatic effects become apparent. For example, nutlin-3 (an Mdm-2 inhibitor and indirect p53 inducer) induces p53/p21 and reversible quiescence in HT-p21 and HT-p16 cells, please note that HT-p21 and HT-p16 are cell lines. But why does it not induce senescence, despite p53/p21 induction? This is because nutlin-3 simultaneously inhibits mTOR and slows down geroconversion [46]. In fact, when added to cells arrested by IPTG-inducible ectopic p21 and p16, nutlin-3 suppresses geroconversion, sustains quiescence, prevents loss of proliferative potential, and renders cells smaller and elongated instead of flat (46). Rapamycin makes cells smaller, but they are still flat (Note: in some cell lines, nutlin-3 does not sufficiently inhibit mTOR and therefore induces senescence [47]).

In agreement with our findings, the work from different laboratories demonstrated that rapamycin decreases senescent markers including SASP [5,16,48–60].

Inhibitors of MEK and PI3K (43), double PI3K/mTOR and pan-mTOR inhibitors [61,62] are gerostatics, which slow down proliferation and geroconversion.

Pan-mTOR inhibitors are even more effective than rapamycin to suppress senescent phenotype [61,62]. They are slightly superior to rapamycin (and other rapalogs) in inhibiting hypertrophy (preventing large cell morphology) and beta-Gal staining and oil red staining (fatty droplets). Unlike rapamycin, they prevent flat morphology. Their advantage is that they inhibit rapamycin-insensitive functions of mTORC1. However, pan-mTOR inhibitors are cytotoxic at higher doses [62].

I suggest a combination of low doses of pan-mTOR or PI3K/mTOR inhibitors plus high doses of rapamycin (or everolimus). At low doses, these inhibitors are expected to moderately suppress mTORC1 functions without toxicity, while high doses of rapamycin may inhibit rapamycin-sensitive function profoundly also without toxicity.

Unfortunately, pan-mTOR inhibitors have not yet been tested on life extension in animals**.** MEK inhibitor (in combination with rapamycin) was tested in Drosophila only [63]).

Replicative senescence

In specific conditions, rapamycin can also delay replicative senescence [60,64–66] and prevent senescence during cell reprogramming [67]. The mechanism is still unclear. Replicative senescence (also known as the Hayflick limit) is an ineffective method of causing cell cycle arrest, which is induced by varying mechanisms after varying number of divisions and at varying times for individual cells. Replicative senescence is an inconvenient model that has no relevance to the organism. Therefore, we will not discuss replicative senescence further.

The notion of geroconversion is somewhat underappreciated

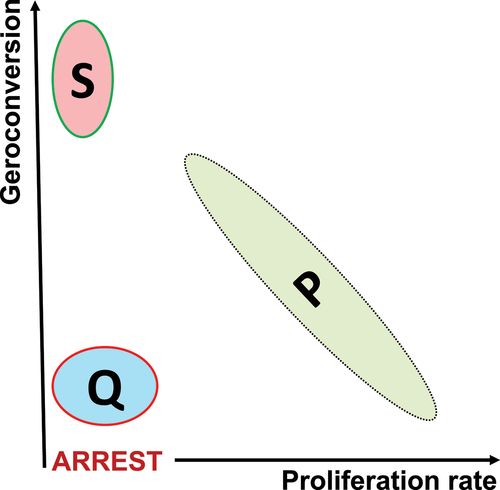

The notion of geroconversion adds the second dimension to distinguish between senescence (S) and quiescence (Q). The second dimension reveals a reverse relationship between proliferation and geroconversion in primary normal cells (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Two-dimensional representation of proliferation P, quiescence Q and senescence S in normal cells.

Two-dimensional representation (proliferation rate vs geroconversion) distinguishes between Q and S in normal cell culture. In standard one-dimensional representation (proliferation rate), both Q and S would be just “proliferation arrest”. The model reveals reverse correlation between geroconversion and proliferation rate in normal proliferating cells.

Noteworthy, geroconversion was described in the organism [68–71].

DNA damage causes cell cycle arrest in the first 16 hours, but the senescent phenotype develops slowly during next 3–6 days. It is obvious there is a separate process apart from cell cycle arrest. This separate process is geroconversion. Without geroconversion, the arrested cell would be unchanged over time. Despite the obvious, the notion of geroconversion is underappreciated for several reasons:

- The confusion between proliferation and proliferative potential. Note: Rapamycin inhibits proliferation but preserves proliferative potential in non-proliferating cells.

- The confusion between irreversible cell cycle arrest and loss of proliferative potential. Note: Rapamycin does not reverse cell cycle arrest, it causes it (in the form of quiescence), but it maintains the proliferative potential in quiescent cells.

- The use of replicative senescence models is complicated by cytostatic effects of rapamycin on cellular proliferation.

- Beta-Gal staining is a marker of both senescence and quiescence caused by serum withdrawal and contact inhibition.

To study the effects of gerostatics on the golden marker, the culture model should meet several requirements:

- To render arrest reversible, the inducer of cell cycle arrest at the beginning should be easily removable (e.g. by changing media). IPTG-inducible p21/p16, sodium butyrate and pharmacological CDK inhibitors are good examples.

- The inducer of cell cycle arrest should not damage the cell.

- The inducer should cause rapid arrest in all (or almost all) cells in the dish. Otherwise, non-arrested cells will take over.

- Gerostatics (e.g. rapamycin) should be added simultaneously (not later) with the inducer of cell cycle arrest.

The origin of hyperfunction theory: personal perspective

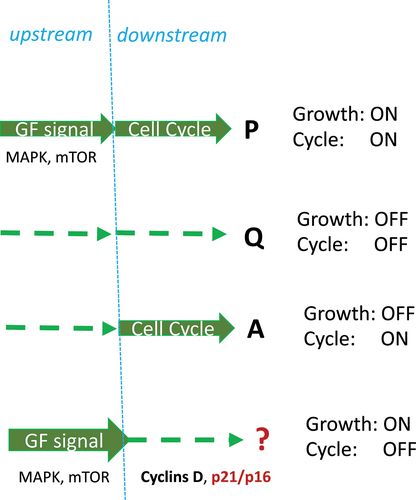

Paradoxes may herald a paradigm shift. At the end of the last millennium, it was paradoxically shown that, in the absence of growth factors, forced activation of the cell cycle (e.g. by transfection with c-myc and E2F) in quiescent cells can cause apoptosis instead of proliferation [7]. Please note, apoptosis is programmed cell death. Furthermore, this happens because growth-promoting pathways that are upstream are deactivated, but the cell cycle which is downstream is forcefully activated.

So, there are three scenarios (Figure 7):

- Growth signaling is ON and the cell cycle is ON (proliferation)

- Growth signaling is OFF and cell cycle is OFF (quiescence)

- Growth signaling is OFF and cell cycle is ON (apoptosis)

- Growth signaling is ON and the cell cycle is OFF (senescence)

Figure 7. Four combinations of growth and cycling: formal approach.

Proliferation P, Quiescence Q, Apoptosis A, and Senescence/Geroconversion ?.

Here, the second paradox is helpful. In proliferating cells, strong mitogenic/growth-promoting signaling such as hyper-activated MEK, Ras, Raf and Akt can cause senescence, instead of proliferation [2–7]. Strong growth stimulation simultaneously induces cyclins and CDK inhibitors (p21, p16), thus causing cell cycle arrest because inhibitors are dominant [7].

As suggested in 2003, this condition of Growth ON/Cell Cycle OFF leads to cellular senescence [7] in the process later named geroconversion [72]. In fact, in the absence of cell division, growth becomes imbalanced, and cells become hypertrophic, beta-gal-positive (lysosomal hyperfunction), hypersecretory and so on. Thus growth factor resistance and insulin resistance develops in compensation [7].

By 2005, numerous deactivating mutations were identified that could extend the life span of model organisms. Among them were components of the mTOR pathway. Since the same pathways are involved in cell senescence and organismal aging, the hyperfunction theory of quasi-programmed aging was developed [27]. Given that rapamycin was available for human use and mTOR was involved in most human diseases, to be useful, the theory became mTOR-centric [27].

So we know that a hallmark of cellular senescence is proliferation-like activity of growth-promoting pathways (such as mTOR and MAPK) in non-proliferating cells. It is growth without purpose and when the cell cycle is arrested, these pathways convert arrest to senescence otherwise known as geroconversion. Additionally the activity of growth-promoting pathways, such as mTOR and MAPK pathways, is high in senescent cells, as if these senescent cells proliferate. However, once again they do not. Furthermore, senescence is understood as not a form of arrest, but as a form of growth albeit growth without an end-goal [25]. We also know that Rapamycin, a reversible inhibitor of growth, slows down mTOR-driven geroconversion. Therefore rapamycin based treatments are critical for anti-aging modalities and thus are a cornerstone for any endeavor in improving your Healthspan.

1. Blagosklonny MV. Rapamycin, proliferation and geroconversion to senescence. Cell Cycle. 2018;17(24):2655–2665. [Taylor & Francis Online], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 2. Serrano M, Lin AW, McCurrach ME, et al. Oncogenic ras provokes premature cell senescence associated with accumulation of p53 and p16INK4a. Cell. 1997;88(5):593–602. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 3. Lin AW, Barradas M, Stone JC, et al. Premature senescence involving p53 and p16 is activated in response to constitutive MEK/MAPK mitogenic signaling. Genes Dev. 1998;12(19):3008–3019. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 4. Blagosklonny MV. The mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway mediates growth arrest or E1A-dependent apoptosis in SKBR3 human breast cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 1998;78(4):511–517. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 5. Deschenes-Simard X, Gaumont-Leclerc MF, Bourdeau V, et al. Tumor suppressor activity of the ERK/MAPK pathway by promoting selective protein degradation. Genes Dev. 2013;27(8):900–915. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 6. Deschenes-Simard X, Kottakis F, Meloche S, et al. ERKs in cancer: friends or foes? Cancer Res. 2014;74(2):412–419. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 7. Blagosklonny MV. Cell senescence and hypermitogenic arrest. EMBO Rep. 2003;4(4):358–362. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 8. Wiley CD, Campisi J. The metabolic roots of senescence: mechanisms and opportunities for intervention. Nat Metab. 2021;3(10):1290–1301. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Google Scholar] 9. Kirkland JL, Tchkonia T. Senolytic drugs: from discovery to translation. J Intern Med. 2020;288(5):518–536. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 10. Coppe JP, Desprez PY, Krtolica A, et al. The senescence-associated secretory phenotype: the dark side of tumor suppression. Annu Rev Pathol. 2010;5:99–118. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 11. Velarde MC, Demaria M. Targeting senescent cells: possible implications for delaying skin aging: a mini-review. Gerontology. 2016;62(5):513–518. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 12. Laberge RM, Zhou L, Sarantos MR, et al. Glucocorticoids suppress selected components of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype. Aging Cell. 2012;11(4):569–578. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 13. Campisi J, Andersen JK, Kapahi P, et al. Cellular senescence: a link between cancer and age-related degenerative disease? Semin Cancer Biol. 2011;21(6):354–359. [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 14. Tchkonia T, Zhu Y, van Deursen J, et al. Cellular senescence and the senescent secretory phenotype: therapeutic opportunities. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(3):966–972. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 15. Wang R, Sunchu B, Perez VI. Rapamycin and the inhibition of the secretory phenotype. Exp Gerontol. 2017;94:89–92. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 16. Wang R, Yu Z, Sunchu B, et al. Rapamycin inhibits the secretory phenotype of senescent cells by a Nrf2-independent mechanism. Aging Cell. 2017;16(3):564–574. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 17. Bent EH, Gilbert LA, Hemann MT. A senescence secretory switch mediated by PI3K/AKT/mTOR activation controls chemoprotective endothelial secretory responses. Genes Dev. 2016;30(16):1811–1821. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 18. Christy B, Demaria M, Campisi J, et al. p53 and rapamycin are additive. Oncotarget. 2015;6(18):15802–15813. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Google Scholar] 19. Blagosklonny MV. Prospective treatment of age-related diseases by slowing down aging. Am J Pathol. 2012;181(4):1142–1146. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 20. Lee BY, Han JA, Im JS, et al. Senescence-associated beta-galactosidase is lysosomal beta-galactosidase. Aging Cell. 2006;5(2):187–195. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 21. Kurz DJ, Decary S, Hong Y, et al. Senescence-associated (beta)-galactosidase reflects an increase in lysosomal mass during replicative ageing of human endothelial cells. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 20):3613–3622. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 22. Frescas D, Hall BM, Strom E, et al. Murine mesenchymal cells that express elevated levels of the CDK inhibitor p16(Ink4a) in vivo are not necessarily senescent. Cell Cycle. 2017;16(16):1526–1533. [Taylor & Francis Online], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 23. Hall BM, Balan V, Gleiberman AS, et al. Aging of mice is associated with p16(Ink4a)- and beta-galactosidase-positive macrophage accumulation that can be induced in young mice by senescent cells. Aging (Albany NY). 2016;8(7):1294–1315. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Google Scholar] 24. Hall BM, Balan V, Gleiberman AS, et al. p16(Ink4a) and senescence-associated beta-galactosidase can be induced in macrophages as part of a reversible response to physiological stimuli. Aging (Albany NY). 2017;9(8):1867–1884. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Google Scholar] 25. Demidenko ZN, Blagosklonny MV. Growth stimulation leads to cellular senescence when the cell cycle is blocked. Cell Cycle. 2008;7(21):3355–3361. [Taylor & Francis Online], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 26. Leontieva OV, Demidenko ZN, Blagosklonny MV. Contact inhibition and high cell density deactivate the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway, thus suppressing the senescence program. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(24):8832–8837. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 27. Blagosklonny MV. Aging and immortality: quasi-programmed senescence and its pharmacologic inhibition. Cell Cycle. 2006;5(18):2087–2102. [Taylor & Francis Online], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 28. Johnson SC, Rabinovitch PS, Kaeberlein M. mTOR is a key modulator of ageing and age-related disease. Nature. 2013;493(7432):338–345. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 29. Blagosklonny MV. Rapamycin for longevity: opinion article. Aging (Albany NY). 2019;11(19):8048–8067. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Google Scholar] 30. Blagosklonny MV. TOR-driven aging: speeding car without brakes. Cell Cycle. 2009;8(24):4055–4059. [Taylor & Francis Online], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 31. Blagosklonny MV. The hyperfunction theory of aging: three common misconceptions. Oncoscience. 2021;8:103–107. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Google Scholar] 32. Blagosklonny MV. Revisiting the antagonistic pleiotropy theory of aging: TOR-driven program and quasi-program. Cell Cycle. 2010;9(16):3151–3156. [Taylor & Francis Online], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 33. Gems D, de la Guardia Y. Alternative perspectives on aging in Caenorhabditis elegans: reactive oxygen species or hyperfunction?Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;19(3):321–329. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 34. Gems D, Partridge L. Genetics of longevity in model organisms: debates and paradigm shifts. Annu Rev Physiol. 2013;75:621–644. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 35. Ezcurra M, Benedetto A, Sornda T, et al. C. elegans eats its own intestine to make yolk leading to multiple senescent pathologies. Curr Biol. 2018;28(16):2544–56 e5. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 36. Wang H, Zhang Z, Gems D. Monsters in the uterus: teratoma-like tumors in senescent C. elegans result from a parthenogenetic quasi-program. Aging (Albany NY). 2018;10(6):1188–1189. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Google Scholar] 37. Gems D. The hyperfunction theory: an emerging paradigm for the biology of aging. Ageing Res Rev. 2022;74:101557. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Google Scholar] 38. Plotz CM, Knowlton AI, Ragan C. The natural history of cushing’s syndrome. Am J Med. 1952;13(5):597–614. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 39. Demidenko ZN, Zubova SG, Bukreeva EI, et al. Rapamycin decelerates cellular senescence. Cell Cycle. 2009;8(12):1888–1895. [Taylor & Francis Online], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 40. Chang BD, Watanabe K, Broude EV, et al. Effects of p21Waf1/Cip1/Sdi1 on cellular gene expression: implications for carcinogenesis, senescence, and age-related diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(8):4291–4296. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 41. Chang BD, Broude EV, Fang J, et al. p21Waf1/Cip1/Sdi1-induced growth arrest is associated with depletion of mitosis-control proteins and leads to abnormal mitosis and endoreduplication in recovering cells. Oncogene. 2000;19(17):2165–2170. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 42. Shtutman M, Chang BD, Schools GP, et al. Cellular Model of p21-Induced senescence. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1534:31–39. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Google Scholar] 43. Leontieva OV, Demidenko ZN, Blagosklonny MV. MEK drives cyclin D1 hyperelevation during geroconversion. Cell Death Differ. 2013;20(9):1241–1249. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 44. Leontieva OV, Blagosklonny MV. CDK4/6-inhibiting drug substitutes for p21 and p16 in senescence: duration of cell cycle arrest and MTOR activity determine geroconversion. Cell Cycle. 2013;12(18):3063–3069. [Taylor & Francis Online], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 45. Demidenko ZN, Blagosklonny MV. Quantifying pharmacologic suppression of cellular senescence: prevention of cellular hypertrophy versus preservation of proliferative potential. Aging (Albany NY). 2009;1(12):1008–1016. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Google Scholar] 46. Demidenko ZN, Korotchkina LG, Gudkov AV, et al. Paradoxical suppression of cellular senescence by p53. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(21):9660–9664. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 47. Korotchkina LG, Leontieva OV, Bukreeva EI, et al. The choice between p53-induced senescence and quiescence is determined in part by the mTOR pathway. Aging (Albany NY). 2010;2(6):344–352. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Google Scholar] 48. Laberge RM, Sun Y, Orjalo AV, et al. MTOR regulates the pro-tumorigenic senescence-associated secretory phenotype by promoting IL1A translation. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17(8):1049–1061. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 49. Herranz N, Gallage S, Mellone M, et al. mTOR regulates MAPKAPK2 translation to control the senescence-associated secretory phenotype. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17(9):1205–1217. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 50. Chen C, Liu Y, Liu Y, et al. mTOR regulation and therapeutic rejuvenation of aging hematopoietic stem cells. Sci Signal. 2009;2(98):ra75. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 51. Iglesias-Bartolome R, Patel V, Cotrim A, et al. mTOR inhibition prevents epithelial stem cell senescence and protects from radiation-induced mucositis. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11(3):401–414. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 52. Mercier I, Camacho J, Titchen K, et al. Caveolin-1 and accelerated host aging in the breast tumor microenvironment: chemoprevention with rapamycin, an mTOR inhibitor and anti-aging drug. Am J Pathol. 2012;181(1):278–293. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 53. Houssaini A, Breau M, Kebe K, et al. mTOR pathway activation drives lung cell senescence and emphysema. JCI Insight. 2018;3(3). DOI:https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.93203. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 54. Summer R, Shaghaghi H, Schriner D, et al. Activation of the mTORC1/PGC-1 axis promotes mitochondrial biogenesis and induces cellular senescence in the lung epithelium. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2019;316(6):L1049–L60. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 55. Luo Y, Li L, Zou P, et al. Rapamycin enhances long-term hematopoietic reconstitution of ex vivo expanded mouse hematopoietic stem cells by inhibiting senescence. Transplantation. 2014;97(1):20–29. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 56. Hinojosa CA, Mgbemena V, Van Roekel S, et al. Enteric-delivered rapamycin enhances resistance of aged mice to pneumococcal pneumonia through reduced cellular senescence. Exp Gerontol. 2012;47(12):958–965. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 57. Gu Z, Tan W, Ji J, et al. Rapamycin reverses the senescent phenotype and improves immunoregulation of mesenchymal stem cells from MRL/lpr mice and systemic lupus erythematosus patients through inhibition of the mTOR signaling pathway. Aging (Albany NY). 2016;8(5):1102–1114. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Google Scholar] 58. Nie D, Zhang J, Zhou Y, et al. Rapamycin treatment of tendon stem/progenitor cells reduces cellular senescence by upregulating autophagy. Stem Cells Int. 2021;2021:6638249. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 59. Gao C, Ning B, Sang C, et al. Rapamycin prevents the intervertebral disc degeneration via inhibiting differentiation and senescence of annulus fibrosus cells. Aging (Albany NY). 2018;10(1):131–143. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Google Scholar] 60. Kolesnichenko M, Hong L, Liao R, et al. Attenuation of TORC1 signaling delays replicative and oncogenic RAS-induced senescence. Cell Cycle. 2012;11(12):2391–2401. [Taylor & Francis Online], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar] 61. Walters HE, Deneka-Hannemann S, Cox LS. Reversal of phenotypes of cellular senescence by pan-mTOR inhibition. Aging (Albany NY). 2016;8(2):231–244. [Crossref], [PubMed], [Google Scholar]